The NFL Draft's 'secret round'

For every player who enters his name in the NFL Draft, the dream is the same: the welcome-to-the-team phone call, the nine notes of the “The Pick Is In” chime, and then their name attached to an NFL team for all the world to see. No matter whether the name comes at the beginning of Night 1 or the end of Night 3, the end result is the same: an NFL team thinks enough of the player’s services to bring them into the fold.

A selection in the draft is the culmination of a lifetime of hard work, a moment of celebration for the player and his family. It’s the first step in a journey that could lead to stardom.

It could also mean a quick end to a career.

Because, while a player picked on Thursday night has a strong chance of finding his way to an NFL starting lineup, numbers from the past 20 years indicate players still on the board after the draft’s third round might very well be better off going undrafted entirely than getting picked in the late rounds. Here’s why.

Undrafted free agents’ unexpected staying power

Conventional wisdom holds that the 250 or so players selected in each year’s draft are the privileged few, the elite of the nation’s football crop, the very best players available at that moment in time.

The truth is much different. Going undrafted isn’t a sign that a player’s career is over. In many cases, it can be the best possible outcome — certainly better than getting drafted in one of the late rounds.

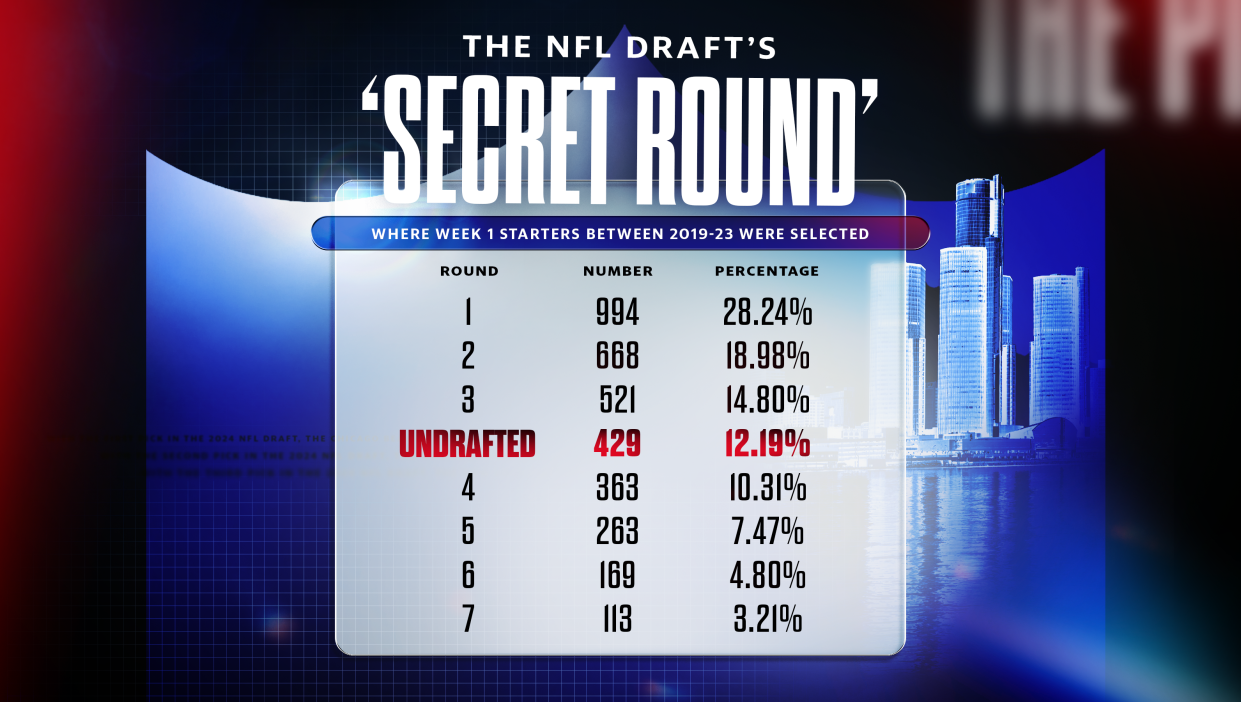

A Yahoo Sports analysis of the past 20 years’ worth of draft picks and starting players found a stark reality about drafted versus undrafted players. When analyzing Week 1 starters across all teams, undrafted free agents (UDFAs) comprised a larger group than players drafted in Rounds 4, 5, 6 or 7. Over some periods, UDFAs are a larger group than players drafted in Round 3.

Using Pro Football Reference’s Stathead Football search engine, we assessed the draft status of every player in the Week 1 22-man starting lineups, offense and defense. This gave us 704 players (22 players x 32 teams) each season, divided into eight categories (Drafted in Rounds 1-7 or Undrafted). We chose this framework for several reasons:

• Week 1 is the point in the season when the best players are most likely to be healthy and in the starting lineup.

• Week 1 is thus the point in the season when spot replacements are least likely to be in the lineup.

• We excluded special teams players and kickers because of the inherent variability and transitive nature of those positions.

In 2023, 194 Week 1 starters — almost 28% — were drafted in the first round of their respective drafts. Another 143 starters, or roughly 20%, were drafted in the second round, and another 107, or about 15%, were taken in the third round. In other words, picks in the top three rounds made up nearly two-thirds of all NFL lineups in 2023.

Beyond that point, though, an interesting trend emerges. As expected, declining numbers of players selected in Round 4 (77), Round 5 (52), Round 6 (33) and Round 7 (18) reached the starting lineup.

However, 80 undrafted players — more than any of the final four rounds — were in starting lineups in Week 1 of the 2023 season. More than 11% of all starters in 2023 went undrafted.

This pattern holds over longer timeframes, as well. From 2019 to 2023, 429 undrafted players — more than 12% — reached the starting lineup. (We counted every season a player started separately; if an undrafted player started all five seasons, that counts as five “undrafted” starts.) That’s fewer than all Round 3-picked starters (521) but more than Round 4 (363).

In the five-year periods from 2014-2018 and 2009-2013, the difference is even more stark, as undrafted players comprised a larger percentage of the starting lineups than players from any rounds except 1 and 2.

“You could make the argument that not getting drafted is better than going in later rounds,” says Mike Tannenbaum, former Jets general manager and Dolphins vice president of football operations. “Undrafted free agents are more targeted to fit with the team. It’s more need-based.”

(An interesting related pattern: excluding free agents from the discussion, the round in which a player is picked is remarkably predictive of their long-term success in the league. You have to go all the way back to the five-year period from 2004-2008 to find an instance in which players from a lower round outnumber players selected in a higher round among starters — and even then, it’s a difference of only eight players picked in the seventh versus the sixth round.)

What does all this mean for the draft process, and what lessons are there for players, GMs and scouts? Let’s dive in.

The benefit of undrafted players

Even a quarter-century on, the patron saint and North Star of undrafted free agents remains Kurt Warner. Every undrafted player dreams of playing in the league; every team dreams of finding a Super Bowl-caliber diamond in the dirt. But the undrafted free agent doesn’t necessarily need to lead a team to a title to be a success; sometimes they fill the right role at the right time, and sometimes their skills blossom only under the tutelage of NFL coaches. Recent notable UDFAs include Pro Bowlers like San Francisco’s Charvarius Ward, Dallas’ Kavontae Turpin and Atlanta’s Younghoe Koo.

From a pure numbers perspective, it’s not surprising that UDFAs make up a larger percentage of the NFL pool of starters than many draft rounds. Every season, the potential pool of undrafted free agents is far larger than the 32 or so players drafted each round. As soon as the draft ends, teams begin a signing frenzy to rope in undrafted rookies. Here’s last year’s roundup; Miami, for instance, signed 21 UDFAs to accompany their five draft picks, while Seattle signed 26 UDFAs after making 10 draft picks.

Plus, undrafted players often enjoy the luxury of being able to negotiate with the team of their choice — or, at least, they’re not restricted to negotiating with a single team. That matters, given the vast potential outcomes for virtually any player depending on their coaching staff. Would Patrick Mahomes have become PATRICK MAHOMES had he been drafted by the Bears? Would Zach Wilson or Josh Rosen have flamed out so quickly had they been drafted by the Rams or 49ers, rather than the Jets and Cardinals?

Undrafted free agents can also take time to develop and demonstrate their skills. This is evident from looking at the number of undrafted rookies who play their way into the starting lineup in their rookie year. In the five years from 2019-2023, only 11 undrafted rookies made the starting lineup, equal to the number of rookies drafted in Round 6 and ahead of only rookies from Round 7 (5). In 2023, only one undrafted rookie — Green Bay wide receiver Malik Heath — was in a Week 1 starting lineup.

The financial risk-reward of an undrafted free agent

It’s here where roster building within a salary cap can come into play.

Every drafted player, even the “Mr. Irrelevant” final pick in the draft, is guaranteed at least some compensation. Spotrac estimates that the final pick in the 2024 draft, which currently belongs to the Jets, will sign a four-year rookie contract in the $4.1 million range, with a signing bonus of about $79,000.

UDFAs, on the other hand, are entitled only to the league minimum — currently $795,000 for rookies, and scaling upward from there, per Spotrac — and then, often for only one year and non-guaranteed.

That lack of a guarantee can work in favor of an UDFA because it allows teams to take a chance on them with minimal risk.

“Typically, what you’re trying to tell a later-round pick or UDFA is, you have a chance to make the team,” Tannenbaum says. “There’s a big difference between being on the practice squad and getting a first-year [rookie] salary.”

How does the draft pick/UDFA option work in practice? Let’s consider a famous late-draft slot: position 199, midway through the sixth round, the famous Tom Brady slot. This is exactly the type of draft pick that’s most vulnerable to an UDFA challenge; nearly 200 picks deep in the draft, teams are more likely to be taking flyers on players or drafting the “best available athlete,” regardless of specific need.

In 2016 the Bengals picked wide receiver Cody Core at 199. Core played four seasons, three for Cincinnati and one for the Giants, seeing playing time in 51 games and catching 33 passes for 388 yards. In that same draft, fellow wide receiver Robbie Anderson went undrafted; Anderson has totaled 5,082 yards and 30 touchdowns playing for four teams.

In 2018, possibly hoping for some of that Brady magic, the Titans selected quarterback Luke Falk at the 199th spot. Falk never saw action for Tennessee, and played in only three games in his career, all for the Jets in 2019. Undrafted that year: quarterback Kyle Allen, who started one season for Carolina and has become a reliable backup for several teams, playing in a total of 30 games and passing for 4,734 yards to date.

In 2020, the Rams selected safety Jordan Fuller at 199th. Fuller enjoyed a successful career for the Rams, starting in 46 of the 48 games he’s played to date, and will suit up for Carolina in 2024. Also in Carolina: undrafted safety Sam Franklin Jr., who has played in 64 of a possible 66 games for the Panthers since then.

Granted, these are highly cherry-picked examples. But the overall trend is obvious: getting picked late narrows options for a player who may not have had many options to start. Undrafted free agents who can navigate the treacherous waters of the NFL free agency process can end up on much more favorable shores than their drafted counterparts.

The future of undrafted players

Data indicates, in a broad sense, that players in Rounds 3 and 4 are now reaching the starting lineups in greater percentages than undrafted players. This holds with the general league-wide improvement in scouting and analysis — given the vast volumes of data now available on most college players, it’s less likely that a diamond will fall all the way through the draft.

“Teams are getting more efficient, that’s why you’ll see so many more trades,” Tannenbaum says. “Teams are targeting certain players and drafting guys for specific needs. They’re looking at cost-effective ways to solve problems.”

For teams, this dynamic emphasizes the need for a college football mentality — always be recruiting, in other words. For players whose phones don’t ring this weekend, there’s still another chance — a good one — that they could be suiting up for an NFL team.