UK ethnic minority women lost jobs and paid less during pandemic, data shows

Work and pay inequalities faced by ethnic minority women in Britain widened during the coronavirus pandemic, as they receive lower pay, and experience higher unemployment rates, a new report says.

According to PwC’s Women in Work Index, pre-existing labour market inequalities faced by ethnic minority women were exacerbated during the crisis as Britain rose on the index.

The annual report measures progress in women’s employment outcomes across 33 OECD countries.

Data shows that ethnic minority women are over-represented in insecure, low-paid jobs, and also experienced some of the largest percentage falls in employee numbers in contact-intensive industries like retail and hospitality which were heavily impacted by COVID lockdowns and job losses.

PwC's analysis factors in individual and occupational drivers of earnings like age, occupation, and qualifications.

In the UK, between July 2019 and September 2021, the unemployment rate for ethnic minority women increased by 2.3 percentage points (pp). This was 0.2pp for white women, compared to 0.3pp for white men and 0.6 pp for ethnic minority men during the same period.

This inequality also extended to pay. In Britain, for every £1 ($1.32) earned by a white man, a woman from an ethnic minority with the same occupation and qualifications earns 87p, while a white woman earns 89p.

"These pay penalties provide compelling evidence that an individual’s race and gender, and the intersection of these two characteristics, are significant determining factors of pay and professional success," said PwC economist Tara Shrestha Carney.

"The implication is that we cannot fix employment and pay disparities by addressing skills gaps alone — there is a need to address the systemic and structural gender and racial inequality which exists in the labour market."

The estimates show that it will take 33 years for the female labor force participation rate to match the men’s — currently at 80%. It will take nine years for the female unemployment rate to match the men’s current rate and 63 years to close the gender pay gap, according to the report.

Read more: Cost of living crisis: Women hit harder by rents than men

PwC's estimates include a "COVID-19 gap", which compared job losses to the employment growth projected before the pandemic. It found there were 5.1 million more women unemployed and 5.2 million fewer women participating in the workforce than would be the case had the crisis not occurred.

Increasing women’s employment across the OECD could add $6tn (£4.5tn) per annum to OECD GDP. Meanwhile, closing the gender pay gap could boost women’s earnings across the region by $2tn per year.

Watch: Why do we still have a gender pay gap?

The UK improved its overall performance thanks to advances in the country’s gender pay gap and an increased share of women in full-time employment.

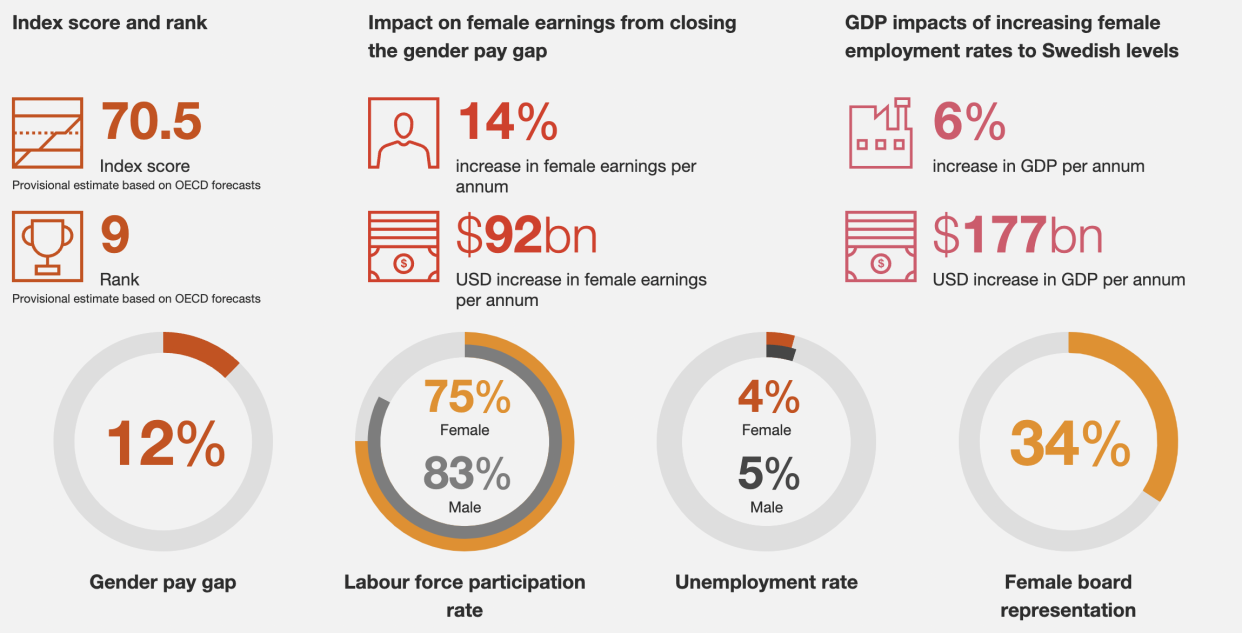

Britain's position rose to ninth place in 2020 from 16th in 2019, strongly outperforming other OECD countries.

PwC's latest ranking puts the UK nearly 10% above the OECD average in 2020. This is the largest annual improvement the nation has achieved in the last decade.

Despite this, Larice Stielow, senior economist at PwC, says this result needs to be treated with caution.

"We must be careful in interpreting this result as a real benefit to women’s employment outcomes," she said.

"A key driver was a temporary fall in men’s median weekly earnings, likely due to the short term effects of the pandemic on wages and the furlough, skewing down earnings."

"Men’s earnings have since rebounded, and the gender pay gap in the UK has widened again by two percentage points, back up to 14%," she added.

However, Stielow said it was "encouraging" that women’s median earnings continued to surge during the pandemic as this suggests gender equality in the UK continues on an "upward trajectory".

Read more: Ukraine war to push up global inflation by 3%

In 2020, the index fell for the first time in its history — by half a point between 2019 and 2020 — due to impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This meant it set back progress towards gender equality in work across OECD countries by at least two years.

This confirmed last year’s predictions that women’s jobs were hit harder than men’s jobs across the OECD by COVID, according to PwC.

The two main factors contributing to the fall were higher female unemployment and lower labour force participation rates during the period.

"OECD data proves last year’s estimates that women took on more unpaid childcare responsibilities than men during the pandemic, causing them to leave the workforce at higher rates than men," the report said.

"Mothers were three times more likely than fathers to report taking on either the majority, or all, of the additional unpaid care work created by school or childcare facility closures."