U.S. Government Scientists Confirm Major Breakthrough In Nuclear Fusion Energy

Since the 1950s, scientists around the world have sought to replicate the reaction that fuels the sun in search of a clean energy “holy grail,” a technology capable of providing nonstop electricity without planet-heating emissions or radioactive waste.

U.S. government researchers just got closer than anyone has before, briefly generating more energy from a fusion reaction than it took to set off, achieving what’s known as “ignition.”

Blasting hydrogen plasma with the world’s biggest laser had already yielded a “Wright brothers moment” in August 2021 when, for a brief 100 trillionths of a second, scientists at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California registered a historic burst of fusion energy. But the 1.3 megajoules generated was only about 70% of the energy fired from the laser.

“Last week for the first time they designed the experiment so the fusion fuel stayed hot enough, dense enough and round enough for long enough that it ignited and it produced more energies than the lasers had deposited,” Marvin Adams, the National Nuclear Safety Administration’s deputy administrator for defense programs, said Tuesday morning at a White House press conference announcing the discovery. “About 2 megajoules in, about 3 megajoules out.”

It’s a major new milestone — the first proof that humanity can harness the cosmic energy released when two lighter atoms fuse into one heavier element, less than a century after the awesome power of splitting atoms debuted as mushroom clouds.

No doubt it’s one of the greatest technological challenges humanity has ever undertaken, but here we are. They’ve done it.Arthur Turrell, plasma physicist and author of “The Star Builders"

“We are in a moment of history, really,” said Arthur Turrell, a plasma physicist whose book “The Star Builders” tracks the growing momentum in nuclear fusion. “No doubt it’s one of the greatest technological challenges humanity has ever undertaken, but here we are. They’ve done it. They’ve proven it can happen.”

The Financial Times first reported the experiment’s results on Sunday.

Conventional nuclear energy is the result of fission, the energy released when the nucleus of an unstable atom divides into two. The first controlled fission experiment took place at the University of Chicago in December 1942. The first commercial nuclear reactor came online in England in August 1956.

Experts say it’ll take a lot more than 14 years to commercialize fusion energy.

For starters, the $3.5 billion National Ignition Facility was built to test atomic weapons, and its array of 192 high-energy lasers is, at this point, outdated and ill-equipped to scale fusion energy experiments.

And inertial confinement fusion — sometimes referred to as laser fusion since it relies on powerful rays to jumpstart the reaction — has long been a secondary priority in the field.

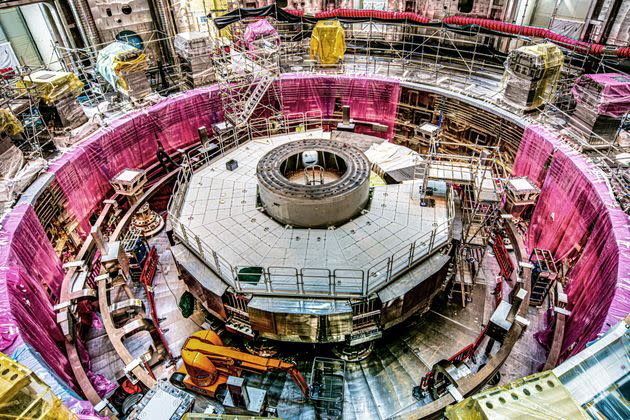

Of the roughly $700 million the federal government spends on nuclear fusion research every year, most goes to paying the U.S. share of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, or ITER. The world’s largest fusion experiment — currently under construction in France with funding from the European Union, China, India, South Korea and Japan — isn’t expected to come online until 2027. But its doughnut-shaped “tokamak” reactor is designed for magnetic confinement fusion, which holds fuel in place with giant magnets while the atoms’ nuclei heat up.

That tokamak design and magnetic process have yielded record volumes of energy for seconds at time, but has yet to come anywhere close to so-called “net energy gain.”

Guests await the beginning of a news conference with U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm at the Department of Energy headquarters to announce a breakthrough in fusion research on Dec. 13 in Washington, D.C.

If magnetic fusion energy is even possible, its commercial use is at least a century away, said Daniel Jassby, a retired research physicist who spent years at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory.

“I don’t know if magnetic fusion is ever going to be feasible,” he said. “Inertial fusion is at least half a century away.”

The latest news from Lawrence Livermore, he said, was in line with his expectations when he published an essay in the journal Inference earlier this year warning that fusion remained “a distant prospect” despite the recent hype.

A nascent industry of a little over two dozen startups has raised over $4.8 billion from private investors, including $2.8 billion in the 12 months ending in June, according to a survey by the Fusion Industry Association. Nearly twice as many companies reported focusing on magnetic fusion as inertial.

But firms like Focused Energy, a German-Texan startup with at least one former Lawrence Livermore researcher on staff, are looking to build a much more efficient laser that could advance what the National Ignition Facility has performed.

“When they designed NIF, it was quite a while ago and the technology has come a long way in that period,” said Debbie Callahan, the former Lawrence Livermore physicist who now serves as Focused Energy’s senior scientist.

Focused Energy, which has raised $15 million so far in venture capital, hopes to complete a pilot plant with its own laser reactors by the end of the next decade, she said.

National Nuclear Security Administration Deputy Administrator for Defense Programs Dr. Marvin Adams holds up a cylinder he says is similar to one used by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratories for a breakthrough in fusion research during a news conference at the Department of Energy headquarters on Dec. 13 in Washington, D.C.

“All fusion startups claim that they’re going to put fusion electricity on the grid in the early 2030s,” Jassby said, speaking generally about the industry. “They have no justification for saying that, there’s no way that’s going to happen with inertial confinement or any other scheme whatsoever.”

Indeed, nuclear fusion startups have for years blown deadlines and moved back the dates at which they claimed they’d build pilot projects, as the news website Grid previously reported.

The nonstop, zero-carbon electricity fission reactors produce has huge advantages over fossil fuels, which destroy the planet’s ecosystems, and renewables, which need huge amounts of space and fluctuate with the weather.

But regulations put in place since the Three Mile Island and Chernobyl accidents virtually ended construction of new reactors in the Western world, and — as a generation of engineers, welders and nuclear scientists retired — the workforce capable of building these complex machines evaporated. The only two new reactors being built in the U.S. are at Georgia’s Plant Vogtle, and the project is years delayed and more than $15 billion over budget.

A view of ITER, the world's largest fusion experiment, currently under construction in France.

About half a dozen companies are now competing to license the first small modular reactor, commercializing the type of fission machine used to power naval ships for electricity production instead. By manufacturing the reactors at scale in a factory, the thinking is that these firms can build new, safer reactors much faster than traditional nuclear plants.

After years of studying why the nuclear industry was in decline, entrepreneur Bret Kugelmass sought to streamline and standardize every possible component for Last Energy, his small reactor startup. Unlike some other small modular reactors in the field, Last Energy’s machines rely on a shrunken-down pressurized water reactor design for which there are existing supply chains.

“We benefit not just from the 300 PWRs out there but the tens of thousands of other steam plants that were built over time and use all the same pumps and valves,” Kugelmass said.

He said he wasn’t worried about the hype over fusion sapping investments from new fission plants.

“Even if you have fusion that works today, the winning clean energy technology will be the one that uses the supply chain that is more common across other industries,” he said. “If they can build an entire power plant, including the fusion part, using all commercially available components, materials, and alloys, then they have a chance at being a low-cost energy provider.”

Still, the “belief that it can work will change about how willing governments, entrepreneurs and maybe even pension funds will be to invest in” fusion, Turrell said.

It may not be the leap needed to replace fossil fuels in the near future, but Jill Hruby, the head of the National Nuclear Security Administration, said: “We have taken the first steps toward a clean energy source that could revolutionize the world.”