Trolling and digital pile-ons: have we created our own version of 1984’s Two Minutes Hate?

In a novel saturated with ideas and concepts that have become familiar even to those who have never read 1984, Room 101 remains one of George Orwell’s most infamous creations. Home to whatever a person fears most, it is the end point of the thought-criminal’s rehabilitation from rebellion to ultimately loving Big Brother.

But it is in the sessions that precede this piece of cruel theatre that the real torture begins; the psychological and physical breaking of the human spirit. The rats that populate Room 101 for Winston Smith are the end game, but the words of Winston’s interrogator, O’Brien, are perhaps even more chilling. It is here that we learn the Party’s vision for a society based solely on hate: “The old civilisations claimed that they were founded on love or justice. Ours is founded upon hatred.”

There can be no love, except for the love of Big Brother. The state has become a stamping boot, one that will last, not for a thousand years, but for ever. There can be no hope of its failure, no matter how much Winston tries to protest: “It is impossible to found a civilisation on fear and hatred and cruelty. It would never endure.”

What follows is a scene wherein O’Brien takes the role of schoolteacher talking down to a misguided pupil. One whose notions are both quaint and delusional. Their exchange is rendered with terrifying effect by actors Andrew Garfield and Andrew Scott in Audible’s new dramatisation – with Scott delivering O’Brien’s words with maniacal relish. O’Brien carefully rebuts Winston’s objections, laughs and mocks his suggestion that the human spirit will always emerge victorious against hate. There is no uprising, no coming revolution. There is the Party, and there is hate, and there is nothing else. It is this realisation that breaks Winston as much as the rats.

In 1984, the state’s orchestrated hatemongering encompasses a daily ritual called the Two Minutes Hate. Orwell does something interesting, and illuminating, with this. Whereas the Ministry of Peace is the war ministry, and the Ministry of Love is a brutally repressive interior ministry, the Two Minutes Hate is not dressed up as Two Minutes Reflection or Two Minutes Concentration: it is exactly what it is, a unique concept in the doublethink world of the Party. Orwell’s decision to call it what it is, shows that the party understands that hate is a vital outlet for its citizens – and that hate needs to be both stoked and rigorously controlled. As Orwell writes: “The horrible thing about the Two Minutes Hate was not that one was obliged to act a part, but that it was impossible to avoid joining in.”

As images of traitors and enemies are paraded in front of the gathered crowd, there is a kind of communion between the viewers. They are whipped into a frenzy, but in a tightly focused manner. It is a bonding exercise, a vent for all the furies attendant on the masses. But then it is over. Hate has been exhausted. The chairs are put away and daily life resumes. There are other outlets for hate – the public hangings, for example; the organised Hate Week during which some of the novel takes place – but again these are strictly managed. Through them, community is created.

Versions of the Two Minutes Hate form part of the playbook for dictators and wannabe tyrants; harnessing the hate of the “other” and directing it at dissidents, minorities, and other opponents. The contemporary weaponisation of hatred often overlaps with orchestrated disinformation campaigns – again, straight out of 1984’s playbook.

But even outside such environments, community is still created by offering up figures for the public to despise.

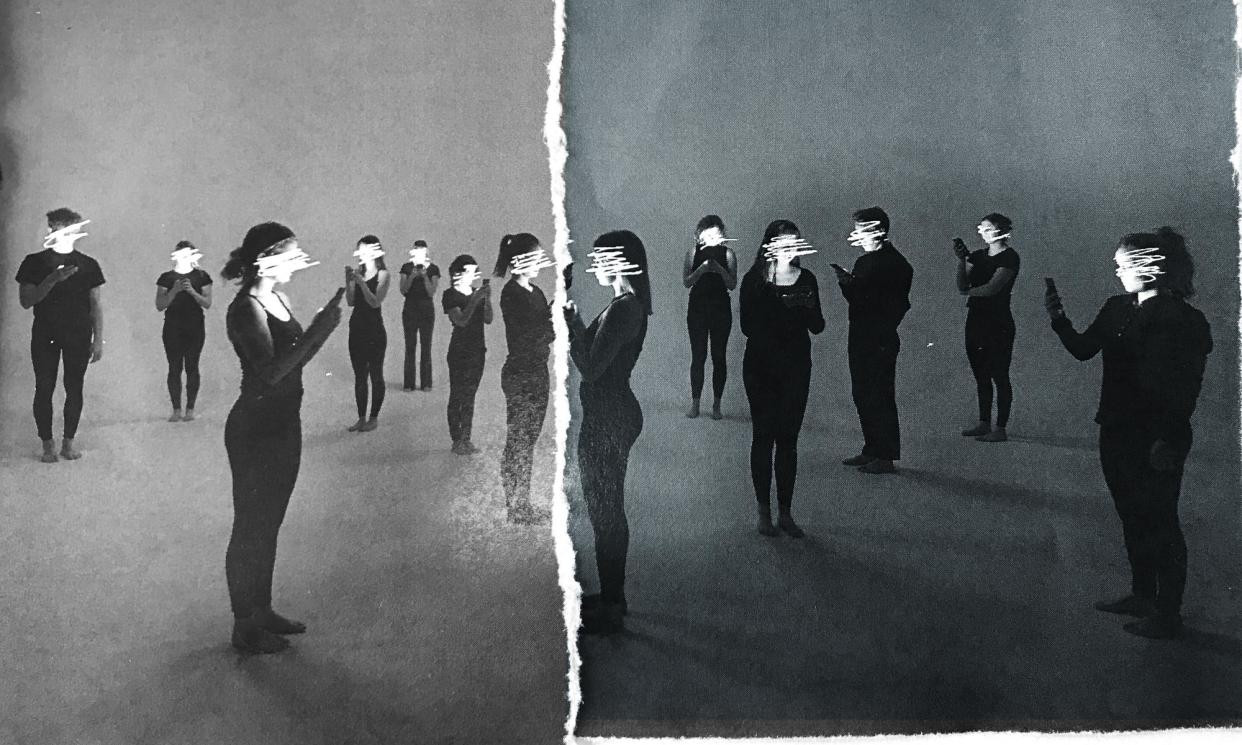

Winston Smith might believe that you cannot form a society based on hate, but scroll through social media on any given day, and he might come to the conclusion that O’Brien was right after all. We see the founding spirit of the Two Minutes Hate as groups coalesce around figures that do not conform to the precepts of that group. Others join, like Winston does, adding their ire and their vitriol against them. While we might abhor the idea of having a designated time for Hate, we are already living within it. A 24/7 Hate, if you will.

Whether it’s a social media pile-on, trolling or cyberbullying, today’s outpourings of digital hatred provide a forum for an ugly form of social bonding. In an academic paper called Haters Gonna Hate, Trolls Gonna Troll, researchers from Reykjavik University concluded that “personality factors may play a role in explaining trolling behaviour, but that personality also intersects with other important factors, such as social rewards and enjoyment of trolling”.

Related: Ignorance ain’t strength: what 1984 tells us about fake news – and how to resist it

These kinds of social and personal rewards are precisely what makes hatred such an effective tool for tyrants and hatemongers, and what gives 1984 its enduring power and legacy: it understands the nuances and small details that can snare people into certainty and conviction. When O’Brien says to Winston: “You are under the impression that hatred is more exhausting than love,” it feels as much a commentary on how we live now, as it does the world of Big Brother.

Unlike the vision set out by O’Brien, however, we have means of escape. But the warning of 1984 is the corrosive effect of hate; how it can be manipulated and weaponised. It is, as Winston discovers after his “rehabilitation”, the way we come to lose ourselves.

Stuart Evers is the author of the The Blind Light and Your Father Sends His Love.

Audible’s new dramatisation of George Orwell’s classic tale stars Andrew Garfield, Cynthia Erivo, Andrew Scott and Tom Hardy, with an original score by Matthew Bellamy and Ilan Eshkeri. Listen now. Subscription required. See audible.co.uk for terms.

Audible and the Audible logo are trademarks of Audible, Inc or its affiliates