‘I tried to scrub the smell of death off of my body...’: A war reporter’s Israel-Hamas diary

‘Nataliya, I’m really sorry to disturb you but there’s something unusual going on.’ My colleague Quique woke me up with a phone call at 7.30am, on a Saturday that came to be known for the greatest loss of Jewish life on any day since the Holocaust – and the start of the most devastating war in the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

It was 7 October 2023, just 12 days after I’d moved to Israel, bringing with me two suitcases and my cat, Fedya. The rest of my belongings were yet to be shipped from Istanbul, where I’d spent the past 18 months after fleeing Russia, my home country, within days of the Kremlin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Staying in Russia was too high-risk, as a Russian national working for a British newspaper.

I was happy in Istanbul but the editors were keen to use my experience elsewhere. The posting to Israel was supposed to offer me a change of scenery after reporting on history-making stories in Russia and Ukraine for more than a decade – and, dare I say it, some respite.

I knew Israel was a volatile place but I was eager to get back to on-the-ground reporting after months of relying on calls and messages while covering the Russian invasion from afar. Nothing could have prepared me for the ferocity of the Hamas-led attack on 7 October, nor the catastrophic, seemingly never-ending war in Gaza it has triggered. From that first day, it was apparent this was a different sort of war to most. A war with, at its centre, a sense of utter hopelessness.

When I arrived in Jerusalem at the end of September last year, there seemed no urgency to plug in immediately. I met Quique, my excellent fixer (a local collaborator and assistant), who has experienced three decades of unrest in the region. ‘Take it easy,’ he advised, ‘explore your neighbourhood, find your grocery store. You don’t have to rush.’

I set about flat-hunting and found a lovely two-bedroom place in a leafy neighbourhood in West Jerusalem. The street happened to be laid on an ancient road going south-west towards the Gaza Strip. I didn’t really register this – more appealing was the fact that it was near an artisan bakery and a wine bar. That first weekend I remember swimming in the warm sea in Tel Aviv; I went shopping at Ikea to kit out my flat. There was a sense of normality, a calmness almost.

Before moving here, I’d been well aware of the country’s history and the serious tensions between Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories – these are, of course, frequently in the news. Just three months before I arrived, an attack had injured nine people in Tel Aviv, but that was the last thing on my mind as I wandered around the supermarket, filling my trolley with a 24-pack of toilet paper, bottles of laundry detergent and paper plates.

Then came Quique’s call.

At first it was unclear what was going on. Initial media reports indicated that Hamas had launched an unusually massive rocket attack: the Israeli military later counted more than 3,000 rockets fired at the country that morning.

When I heard the first blaring siren over Jerusalem, an official alert to warn the public of an attack, I had no idea what was happening. Sitting on the floor against the wall, as far as possible from the windows (a trick I’d learnt from Ukrainian friends living through Russian bombings), I looked at Fedya, but he seemed completely unfazed. Through the panoramic windows of my flat, overlooking a park where the Israeli parliament is situated, I could see streaks of white smoke: Iron Dome missiles launched to shoot down Hamas rockets.

It’s not going to get worse, I reassured myself. Then came the emerging reports of ‘infiltrations’ – or Hamas gunmen armed to the teeth, running around and massacring civilians in kibbutzim and villages on the Israeli side of the border with Gaza. They were so alarming and the rocket attacks so unusually numerous that rather than leaving immediately to report on what was going on, as we ordinarily would, Quique and journalists from other British newspapers suggested we stay put until the picture was clearer.

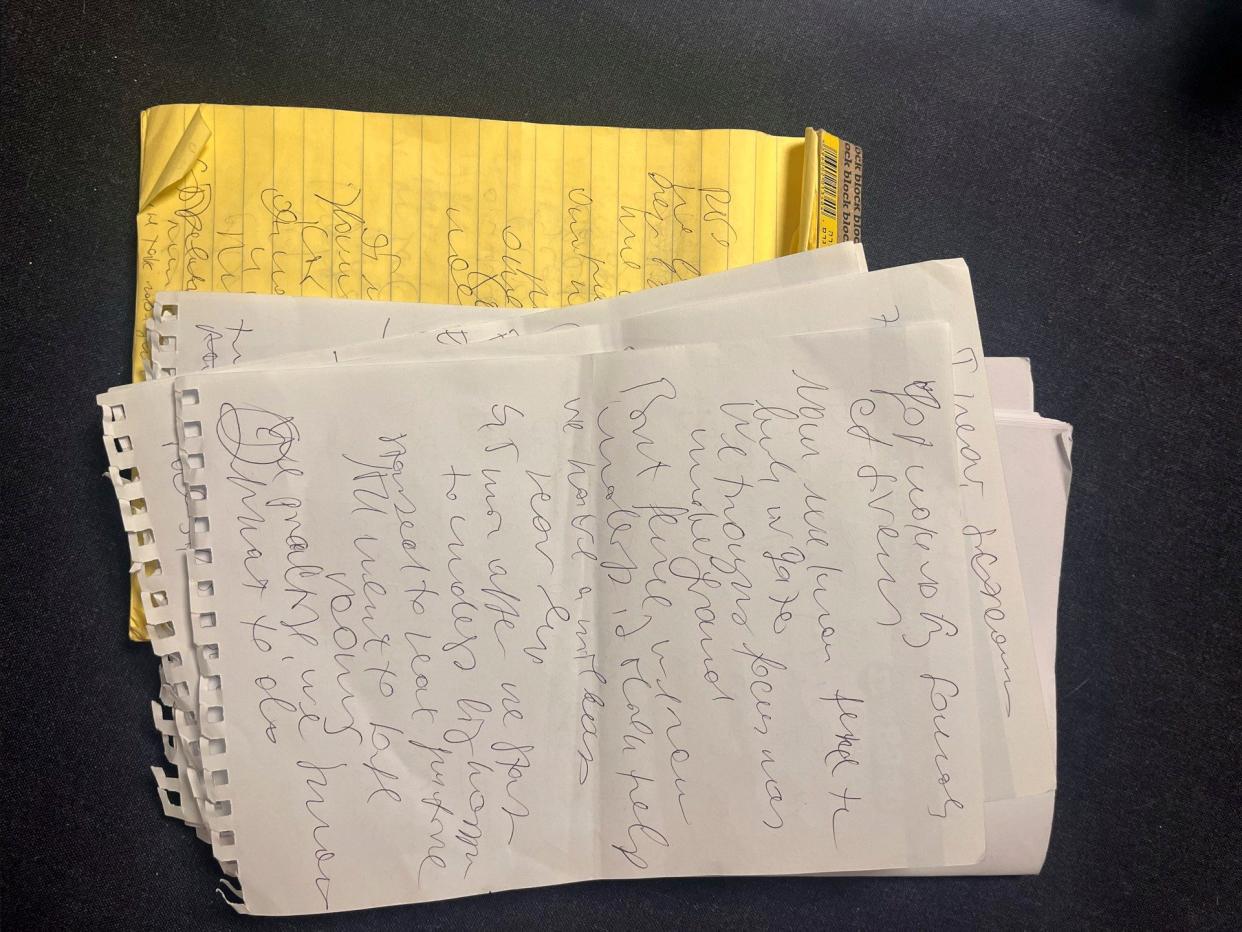

With barely any belongings – they were still stuck in transit – I felt ill-prepared. I didn’t even have a notebook and the shops in Jerusalem were shut, so I improvised, borrowing paper from wherever I could (including a hotel reception). The following day Quique and I hit the road, crisscrossing the battered south of Israel.

Hamas fighters were out roaming the south for 72 hours after the attack, and the dusty road from the city of Be’er Sheva to Gaza was deserted except for soldiers at an improvised checkpoint, who told us there was a new infiltration nearby so we needed to turn back. As we did, I spotted the sign for a nearby town – Ofakim, a name I had heard as one of the places overrun by Hamas. We decided to visit.

On the road into Ofakim there were two charred cars with white number plates rather than yellow Israeli ones. They read: Palestine. The doors were open, the upholstery ripped out – apparently they’d been inspected by an Israeli bomb squad.

In the town, traces of the battle were fresh: next to a house pockmarked with bullet holes, where Hamas had held hostages, a group of plain-clothed police officers were laying candles and holding a prayer. Their colleagues had died in battle here less than 24 hours earlier; the asphalt was smeared with blood.

It was only after the owner of a house across the road played us a recording from a video intercom – showing two militants, one with a rocket-propelled grenade over his shoulder, ringing his front doorbell – that we took in how immediate the danger was.

It would be another 36 hours before the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) – which had been caught completely by surprise by the attack – rounded up or killed the remaining Hamas fighters. Some were still roaming the streets of small towns on the edge of the Negev desert. One wrong turn and anyone could come face-to-face with a terrorist.

Nor was it apparent, in those early days, the scale of the tragedy that had unfolded. More than 1,100 people were killed and some 250 hostages taken in the 7 October attack – 30,000 more would be killed in the strikes on Gaza that followed, according to the Hamas-run health ministry. But the number of casualties and hostages was, at that point, unconfirmed – I only got a sense of the scope of it when I went to a glass office building near Ben Gurion airport, close to Tel Aviv, which had been turned into a makeshift DNA-collection point.

Hundreds of people were filing into the building, clutching plastic bags containing the belongings of a missing relative: a toothbrush, a T-shirt. Valentina Gusak told me she was waiting for her 21-year-old daughter Margarita to resurface. She had been attending a rave in the desert, and had stopped answering the phone that Saturday morning.

‘We hoped our kids might come out of there but there is nothing,’ Valentina said. I sent her a few messages afterwards to check in, but then stopped. I was witnessing so much pain and destruction on a daily basis, I did not have it in me to get closer to another personal tragedy. Days later, Margarita’s name appeared on the official list of casualties.

In my time in southern Israel during the first two weeks after the massacre, I had a few close brushes with mortal danger. But if I had dwelled on them, I would not have been able to keep going.

War reporting doesn’t come with a handbook. I did a journalism course following my English degree, but mostly I have devised my own coping strategies from 16 years on the job. My strategy here was simple: I made the decision to drive back to Jerusalem every night – partly I worried for my cat, but mostly I wanted to sleep in my own bed. Quique and others stayed in the south at a no-frills hotel, precariously close to the Gaza border. I felt my three-hour round-trip commute was worth it.

It was on one of these commutes to the south, which was still being pummelled by Hamas rockets, that I discovered that 24-pack of toilet paper still in my boot, and a bag full of laundry detergent wedged between the back seat and the driver’s seat. Those early days had been so hectic I hadn’t even stopped to unpack.

I drove with other journalists when I could; it was safer. On 10 October, we found ourselves on Route 234, which leads to several kibbutzim that had been ravaged by Hamas. Bodies of half-naked fighters, blackened and bloated from the scorching sun, were still lying in the field outside the kibbutz of Re’im. Our driver spotted a cloud of smoke moving towards us on the empty road. We had not heard any explosions. But what else could it be?

Before I could panic, the cloud started to dissipate and we saw a dozen tanks roll past, churning up the ochre dust. The tanks were driving towards Gaza. I was just relieved to know there was no explosion up ahead. The heavy weaponry moving past didn’t faze me.

In the town of Sderot, one kilometre east of Gaza, I went to see a woman who had hidden in her flat with her daughter for three days as Hamas fighters – holed up in a police station just outside her windows – fought the Israeli army. Katry Kamenetski talked about hearing ‘this weird sound, like rain’ before she tiptoed to the window with her daughter.

Just across the road a group of men in black with white headbands were moving past – members of another of the main militant groups in Gaza. The sound was in fact gunfire. Kamenetski was clearly still in shock. Her calm exterior made it doubly surreal to hear her story.

As I left her home, air raid sirens started to wail. In the centre of Israel, there is time to reach safety, but here, near the border, it is hardest for the Iron Dome to intercept rockets. I knew I had seconds. Rushing back to the apartment block, my team ran down the steps to a basement – it was locked, so Quique, another colleague and I huddled in the doorway, waiting for the rockets to pass.

On the drive away, back to the city of Ashkelon where I’d left my own car in a hotel car park, I was scrolling through a news feed and came across a statement from Hamas’s al-Qassam Brigades: it warned the residents of Ashkelon they had until 5pm before a massive attack would be launched. ‘We should probably drive straight to Jerusalem? Do you really need your bag?’ asked the other journalist travelling with us. I agreed. The bag wasn’t worth the risk.

Once out of the reach of the short-range missiles, we pulled up at a petrol station about one hour from Jerusalem and camped at a café to type up our dispatches. As we were filing, Quique’s wife telephoned: she’d heard that the hotel where he’d intended to stay had just been hit by a missile.

Throughout this time, it was not the physical danger or the graphic destruction that was the most terrifying part. I have seen much death and devastation during my trips to Ukraine in 2014 and 2015, and Syria in 2017. But there it was different, the impact of artillery where people died because someone dozens of miles away pressed a button. It was tragic in the extreme but there was something removed about witnessing a war where both parties could claim they hit a school or a residential building by mistake. The killings in Israel could not have been more deliberate or more vicious.

On day five, I was among the first group of reporters that the IDF allowed into Be’eri, a kibbutz that would become a byword for Hamas atrocities. It was the combination of contrasting scenes – manicured lawns, lights still on in the kitchen and corpses in body bags outside – that made that place so utterly devastating. Then there was the smell.

Later that day, a colleague who was waiting outside asked: ‘So what did you see?’ It’s not what I saw, I admitted. It was the stench of rotting corpses that was overwhelming. The kibbutz was empty, except for military officers who had fought here a few days earlier and were now showing us around. Some of the officers, who had ample battlefield experience, recalled scenes the likes of which they had not seen before: civilians including children murdered inside their own homes. When the army escorted us away after an hour, I felt relieved.

I dictated my story in voice notes – I was too exhausted to write it myself – then got behind the wheel to drive home. Shaken, I drove along the pitch-black road late at night, with the windows down so I could hear any sirens. As I raised my hand to scratch my nose, I could still smell it, that stench. I smelled of it too.

Back in Jerusalem, on the landing outside my front door, I took off my shoes, then peeled off all of my clothes in the doorway. I didn’t want to carry it with me. In the shower, I scrubbed and cleaned for twice as long as I normally would as I still wasn’t sure the smell of death was gone.

Then I had a breakdown.

It was a few days later that I hit my lowest point. By now I’d been working for two weeks with no break. I found myself lost on the road from Jerusalem to the West Bank city of Ramallah, on my way to meet a local fixer and conduct interviews. I had to go down the same road three times, mistakenly driving to an illegal Israeli settlement, before I found the correct turn, and I was an hour late for the meeting.

On the outskirts of Ramallah, we met Sayed Wadi, whose uncle and cousin had been killed earlier that week by Israeli settlers, two of the recent deaths in an underreported, escalating spiral of violence in the West Bank. We struggled to find other people to go on record about tensions: typically talkative shopkeepers around Al Manarah square all asked for their full names to be withdrawn, fearing reprisals from both sides. ‘No one feels safe. We know the IDF can come in and storm Ramallah if they wanted to,’ a jewellery store employee told us.

Exhausted and hungry, having not eaten all day, I stopped at a Palestinian-run hotel in East Jerusalem – one of the nice places I knew would be open while the rest of the city was still quiet. Sitting in the gorgeous inner courtyard, I wolfed down a kofta and realised that I was hyperventilating. My whole body was contorted with stress. I wanted to cry but couldn’t.

My editor kept calling. ‘I can’t eat and file at the same time,’ I texted. And I just sat there, feeling miserable and lonely. The restaurant was popular with visiting journalists who had recently flown in to cover the story and they looked full of energy. I watched in amazement at people laughing and enjoying their wine.

All I could think was: ‘Why am I doing this? What’s the point of it all?’

I have always loved my job. I felt privileged to get to know people from all walks of life – from Ukrainian coal miners and Russian drag queens to Bedouin farmers. I was never under any illusion that my work could change the course of history, but I felt giving people a voice could help them.

In the Holy Land, my work seemed a pointless and also thankless task: by that time I had started to face anger and criticism from both Israelis and Palestinians, who accused me of not being sympathetic. And whatever my colleagues or I wrote did not budge public opinion among those siding with any party.

I also felt isolated, thrust into covering this war without a support network like the ones I’d built in Russia or Turkey. Quique turned out to be an excellent colleague, but he had other gigs and I was on my own a lot.

By some unimaginable force, I filed my story an hour later and went to get my car. As I started to manoeuvre out of the parking spot, I bumped into the car behind me. The next morning, my editor told me to take a day off. I was too burnt out, he said. I spent it watching some forgettable series and walking in an empty park.

It struck me that the Hamas attack and the war unleashed by Israel had poisoned whatever good impressions I might have had of my new home. My leafy, laid-back neighbourhood, which I would otherwise adore, had an imprint of the atrocities on both sides of the conflict.

Gradually, shops and cafés reopened, but I’d go to my hipster coffee shop and it would be full of people carrying automatic weapons: young women, men in flip-flops, fathers with dogs. All were reservists or active soldiers, having to keep their weapons with them even when off-duty. The locals didn’t seem to bat an eyelid.

Many of the Jerusalem-based journalists seemed similarly unfazed by all they had witnessed. ‘It’s tough,’ they’d shrug – but it’s ‘definitely going to get better’. One told me repeatedly that she was ‘fine’, then after months she too crashed. Arriving at my place in late December, she admitted she’d spent days in bed, mentally exhausted. I told her I understood.

The only thing that kept me from quitting – a recurrent thought – was leaving the country for short breaks. Wherever you go within Israel there are reminders of the disaster: posters of smiling Israelis now in captivity, car stickers promising a war until the bitter end, or the unmistakable buzz of Gaza-bound transport planes and fighter jets overhead.

I remember the joy of landing in a grey and rainy Amsterdam on my first trip away. Nothing there reminded me of dusty Israel with its merciless sun. Returning to Jerusalem afterwards was not easy. When the airline rescheduled my flight to an earlier date, I broke down in tears. I couldn’t face going back.

Since then, I’ve tried to get away every six weeks. Every time that break gets closer, I find myself counting down. Some sense of normality has been restored to Israel: rush-hour traffic clogs the roads even in the south these days, and the beach in Tel Aviv is brimming with people.

But there is still no hope for an end to the war in Gaza, and Israeli media are talking about an increasing possibility of a war with Hezbollah in the north of the country.

Months in, my belongings finally turned up. They’d been stuck in customs, thanks to the war. It was surreal to see it all, my furniture, books and linen, still smelling of Istanbul, in the new surroundings. But there was a sadness to it too, an urge to pack up and move back to where I came from.

That urge still hasn’t fully passed. I’m waiting to see if it ever will. All I know is I need to find somewhere to call home.