Can the story of Mungo Man be the ‘healing glue’ of the nation 50 years on from the monumental discovery?

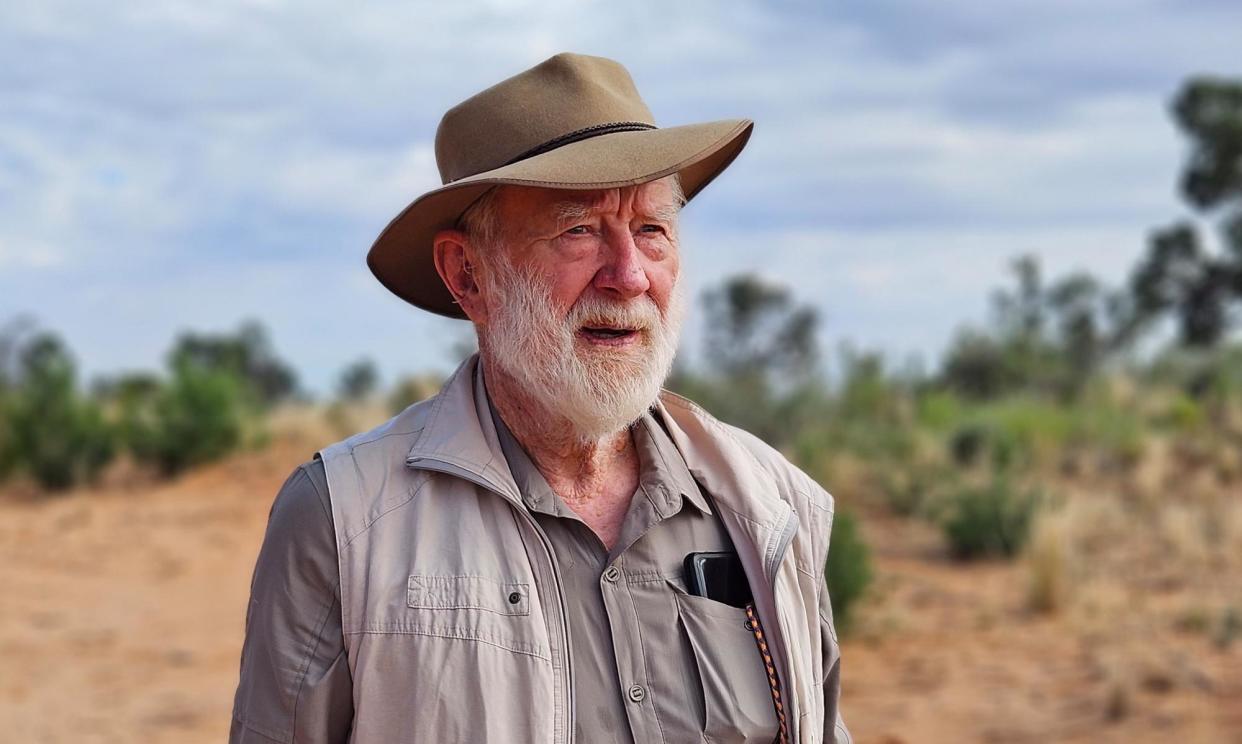

Five decades after significantly enhancing understanding of the tens of thousands of years modern humans have inhabited Australia with his discovery of ancient “Mungo man”, Jim Bowler has returned to the dry lake that staged the momentous encounter.

That day – 26 February 1974 – would change scientific understanding of human antiquity and prove what Australian Indigenous people have always known: they have been here for as good as forever or, in the case of Mungo Man and Mungo Lady – also found by Bowler in 1968 – 42,000 years and counting.

Bowler, 94, thought it “essential” to be in the Willandra Lakes region last Monday, 50 years to the day later, with family and representatives of three recognised traditional owners – the Barkandji/Paackantji, Mutthi Mutthi and Ngiyampaa. He wanted to be there among them, especially some of the elders, to contemplate all Mungo Man has imparted and what he might now inspire for the future of Australian racial conciliation.

Bowler was a young, adventurous man when he encountered the bones of Mungo Lady and later Mungo Man. The father of six operated alone, wandering Willandra Lakes for weeks at a time investigating rock formations and all the while encountering ancient signs of human life around what had been a vast inland sea.

Bowler’s primary professional interest was the geological evidence of climactic change and “the ice age story”. But he was aware – especially after locating the bones of Mungo Lady – that there was “much more waiting to be told” about human antiquity on the Australian continent. His discoveries would arguably add as much or more to the sum of knowledge about evolutionary biology as climate change and the ice age.

Perhaps it’s unsurprising, then, that he should so vividly recall the sunny, cool late summer morning he came across the complete skeleton of Mungo Man who, like the fragmented remains of Mungo Lady, was subject to sophisticated funerary rites involving ochre and fire.

“When the rain stopped there was an opportunity to go out and investigate because rain invariably exposed the new [archaeological material],” he says. “I was always very much aware of the importance of … Mungo Lady. [But] her remains were highly fragmented – they’d been burnt and they were sitting already exposed – so there was no actual understanding of the environment [at time of burial] … but I always had in the back of my mind that there was more evidence of people and so you keep going on looking.”

“There were so many rich signs of human habitation … fish remains, stone tools, middens – it was a goldmine for a geologist. When I noticed the chip of white bone, I thought first of all it was a wombat … but I went over and had a brief look and it was quite different and I brushed away a bit of the sand and revealed a bit of the mandible, the teeth and the jaw. So, this was evidently somebody human.

“I had no idea right then whether the cranium meant that the full body was there but it was sufficient to excite the possibility that here we had evidence of another ancient human deeply in the dune.”

Throughout the 19th and well into the 20th centuries physical anthropologists and anatomists had, through the widespread theft and collection of human skulls, tried to prove Australian Aboriginal people represented a step in the evolutionary chain between ape and modern people. While this theory was already being debunked, some researchers were still looking for signs of Neanderthal and Homo erectus in the remains of Aboriginal people stolen from traditional burial grounds – though none nearly so old as Mungo Man and Lady, inhabitants of the last ice age.

“I realised that it was the beginning of a new day [of knowledge],” Bowler says.

Within 48 hours his associates from the Australian National University – chiefly Bowler’s mentor John Mulvaney – known as the father of Australian archaeology – had arrived to excavate the bones.

“So we were then just brushing away the sand cover and very quickly we saw unfolding before our eyes this remarkable testimony to human antiquity deep in the core of the ancient dune.”

Bowler concedes today that the events were “exciting” and inspired “a sense of elation” among the academics, of whom he is the last alive. But with hindsight, he suggests such elation and academic pride can be “dangerous” when dealing with the removal of ancestral remains no matter what scientific knowledge they might advance or myths debunk.

The removal – or as some Indigenous people say, stealing – of the bones was not broadly controversial at the time, coming as it did after a long Australian tradition of cultural theft of ancestral remains, not least by Murray Black, who supplied hundreds of skeletons and skulls to the Australian Institute of Anatomy. As a much younger man in Gippsland, Bowler knew and was appalled by Black.

Asked if it felt “heretical or disrespectful” to remove the Mungo remains, Bowler says, “not at the time”.

“Sadly at that stage there was no known presence of Indigenous people [as local custodians] – no one with whom we could consult, let alone share the significance of that occasion, or [from whom to] request removal [of the remains],” he says.

“Science had been operating on some disgraceful treatment of Indigenous remains. That sense of disrespect had not yet dawned … There at the time was not … a conscious reflection of shame. But it is now seen as a gross misrepresentation of what we should have been doing … We would treat those remains very differently today.’’

Contact with traditional owners – led in part by now deceased Mutthi Mutthi elder Alice Kelly – did not happen for several years, by which time Mungo Man and Lady were secured at the ANU.

Related: Mungo Man: the final journey of our 40,000-year-old ancestor

Despite the exhaustion of scientific testing on the remains and Mungo national park having been declared a Unesco world heritage site in part due to its unique global human connection, there was entrenched institutional opposition to Mungo Man’s return to country. With the traditional owners, Bowler and Mulvaney agitated for the remains to be taken home and respectfully interred. Mungo Man was brought back to country in 2017 after Mungo Lady was returned 1992. Both were kept in a secure facility associated with Mungo national park.

To the consternation of some traditional custodian elders, the bodies were secretly reburied in 2022. The reburial was put forward by the Aboriginal advisory group comprising members of the three traditional owner groups that advises the New South Wales bureaucracy on traditional lands management at Willandra Lakes region. Some individual members of the advisory group opposed the reburial.

The reburial has been divisive in local Aboriginal communities. Some wanted a more monumental interment, others a memorial. Jason Kelly, the grandson of Alice Kelly, remains angered by the secret reburial, which he tried to stop.

“It goes against my grandmother’s wishes, who didn’t want them secretly put into the ground – but [into] a keeping place, respectfully and securely.”

Kelly and his father, Danny Kelly (the only living child of Alice), and his uncle, Ngiyampaa elder Roy Kennedy, now in his 90s, were among those traditional owners who joined Bowler and his family on the shores of Lake Mungo this week.

Bowler and several elders had hoped to visit the reburial site. But the advisory group rejected the proposal.

“It was critical for them to be able to be there with Jim,” Kelly says. “It was wonderful to be there but it was disappointing that the elders could not go out to the actual [secret] reburial site. And it was disappointing for my father and Uncle Roy that the whole country didn’t realise that this was the 50th anniversary and what Mungo Man means to the country and the world.”

While Bowler said he felt the need to be close to where he discovered Mungo Man, the day was also tinged with disappointment that he could not go to the place of reburial and that these oldest discovered Indigenous Australians had been buried without ceremony.

“They did not deserve to be secretly buried without honour,” Bowler says. “In contrast to the ritual ceremony that was enacted there 40,000 years ago, the secret reburial remains a sad moment. Though it’s not one that we want to concentrate on. Time has passed. Some mistakes have been made – we’ve all made mistakes. We now have to move on to the next step.”

That step, he says, should be a year-long dialogue of conciliation “to find that healing glue” in the wake of the defeat of the constitutional recognition referendum last October.

“There is a need for healing – the need for dialogue between the different cultures has not been resolved. With the failure of the referendum, there is an urgent need to search for the healing glue. What is it that can now unite the nation? I’m suggesting it is the example of the Mungo people and their deep connection to the land and the spiritual dimension that that embraces, as the humans most closely connected to the cosmos.”

Kelly agrees.

“His proposal for a dialogue around Mungo is spot-on. My grandmother always promoted it as a place of healing. And as a place of education for all Australians … We have never come close to realising the potential of Mungo as a place of global cultural and spiritual and human importance.”

Bowler, at 94, may yet return to Lake Mungo. But regardless, the conversation his discovery sparked 50 years ago – for all its resulting human importance and anguish – promises to continue.