Darwin’s plant specimens stored for 200 years to go on public display

Plant specimens collected by Charles Darwin on the voyage of the Beagle have been unearthed in an archive at Cambridge University.

The rare specimens, which have been stored in the archives of the Cambridge University herbarium for nearly 200 years, were given by Darwin to his teacher and friend Prof John Stevens Henslow, the founder of Cambridge University Botanic Garden.

Now they are going to be unveiled to the public for the first time in a Channel 5 TV documentary that explores the relationship between Darwin and Henslow.

“Henslow was a pioneer of botanical teaching and a great mentor to Darwin,” said Dr Edwin Rose, a science historian at Cambridge. He said Darwin, who studied theology at Cambridge, took Henslow’s botanical course three times.

Henslow, a local reverend, taught what was then called natural theology. “This was all about collecting examples of natural creation – ie numerous specimens of different plant species – so they could understand the wisdom of the divine creator and how God created the world,” Rose said. “That was one of the major drivers for undertaking studies of the natural world in the early 19th century.”

When the aristocratic captain of the Beagle, Robert Fitzroy, sought a gentleman naturalist to accompany him on his voyage in 1831, it was Henslow who, after turning down the role himself, recommended 22-year-old Darwin for the position.

Darwin then faithfully posted plant specimens back to his old tutor, whose replies, praising his work but complaining about his packaging, are preserved for posterity in the Cambridge University library.

“Anything Darwin could collect and send to Henslow was seen as an asset because Henslow was actively building the Cambridge botanical museum collection at the time,” Rose said.

This was envisaged as a “massive” teaching resource to facilitate Henslow’s pedagogical programme, which attempted to “understand the design of the Creator” and the infinite extent of God’s creation.

As a result, the university holds at least 1,000 specimens collected by Darwin in its herbarium, which was established in 1761 and now consists of about 1.1m plant specimens from all over the world, including 50,000 “type species” – the original specimens used to describe new species.

“Nearly all of the plants Darwin collected, that are now in the herbarium, are type specimens,” Rose said. “He had a great eye for spotting species new to European science at the time. Nearly everything that he collected, nobody in England had ever seen before.”

This includes a specimen of cucumber that Darwin collected that is the only representative of that species known to scientists, implying it may now be extinct.

Although the herbarium’s collection has been accessible to Cambridge scholars since its inception, it has never been open to the public and Rose said some of the specimens collected by Darwin had never been properly studied.

Curators suspect they may have lain practically untouched in the herbarium’s vast collection since Henslow first received, identified and catalogued them, decades before Darwin published his theory of natural selection.

“There are treasures that are still waiting for scientists to come and examine them,” said Rose.

One “recent find”, a specimen of lichen whose label states it was collected by “C. Darwin” in 1833, rests loosely on the piece of paper it was pressed on to. “It hasn’t even been mounted or glued on,” Rose said.

Another specimen of fungal herbarium collected by Darwin in Brazil was discovered in the archive wrapped in the original newspaper that Darwin used to preserve his finds on the Beagle, revealing how 19th-century botanical collecting practices worked in challenging, tropical, humid environments “when drying out plants is difficult”, Rose said.

This brings scientists “just that little bit closer to the actual moments when these specimens were found, preserved and wrapped by Darwin himself,” he said.

Two seaweed specimens collected by Darwin on the shore of Tierra del Fuego in 1833 correspond with letters Darwin wrote saying he would never forget the “yell” the Indigenous people living on the South American archipelago made when they saw him entering the beach.

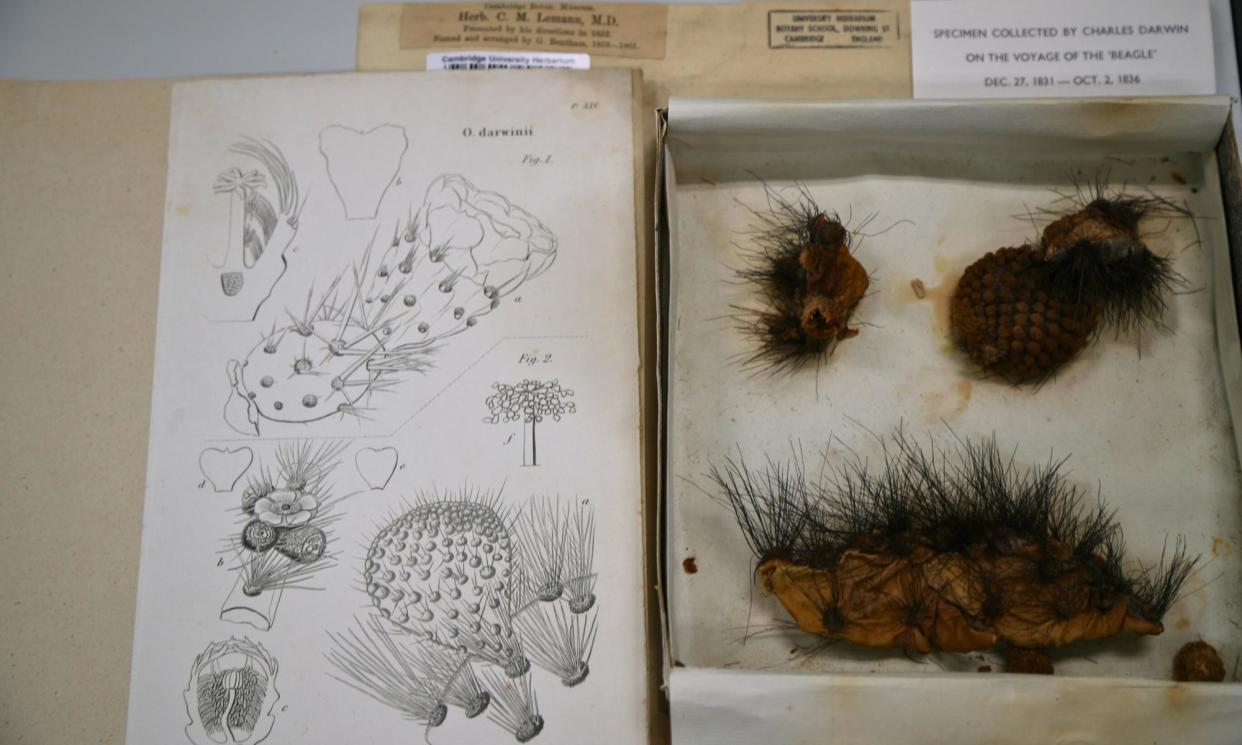

Another “neglected” specimen to be showcased in the Channel 5 documentary – Susan Calman’s Great British Cities, airing next Friday – is an Opuntia (prickly pear) cactus.

This species was “totally unknown” to Europeans when Darwin sent it to Henslow, recording his observations of its role in the Galápagos Islands. “Darwin observed both the lizards and the birds using it as a major supply for food and water,” Rose said. “Understanding these broader interactions between nature – how different food chains work, but also the unique, environmental conditions that cause these animals to evolve in a very specific way – laid the foundations for Darwin’s evolutionary theory.”