Not a 'smoking gun': No proof expanded unemployment benefits are killing the economic recovery

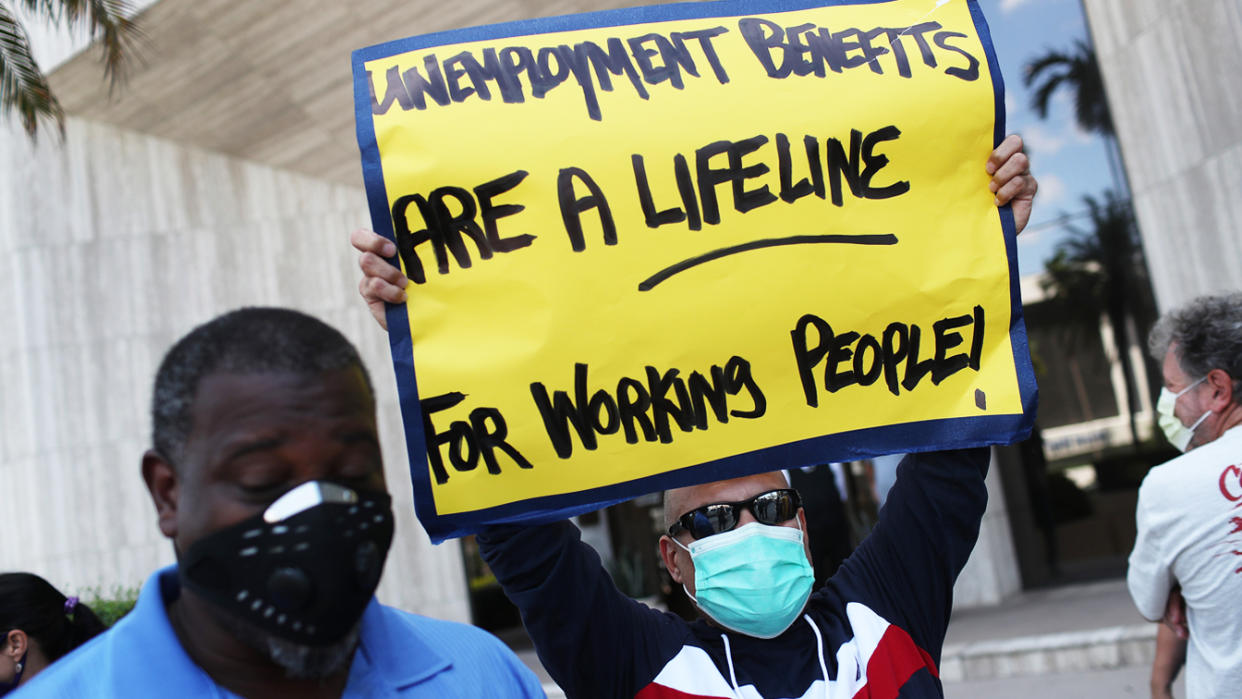

When an underwhelming job report was released in early May, a number of politicians and advocacy groups pointed to one key reason for the slow growth as the country continued to work its way out of the pandemic: Expanded unemployment benefits from the federal government.

“The disappointing jobs report makes it clear that paying people not to work is dampening what should be a stronger jobs market,” said U.S. Chamber of Commerce EVP Neil Bradley, referring to the enhanced unemployment insurance providing out-of-work Americans with a supplemental $300 per week through the end of summer.

Republican governors across the country agreed with that assessment, saying they would be ending the supplemental benefits prior to their set expiration on Sept. 6.

“Montana is open for business again, but I hear from too many employers throughout our state who can’t find workers,” Montana Gov. Greg Gianforte said in a statement announcing he was cutting the program off early in his state. “Nearly every sector in our economy faces a labor shortage.”

“What was intended to be a short-term financial assistance for the vulnerable and displaced during the height of the pandemic has turned into a dangerous federal entitlement, incentivizing and paying workers to stay at home rather than encouraging them to return to the workplace,” said South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster.

The narrative gained traction among many Americans, with a May poll from Yahoo News and YouGov finding slightly more respondents (43 percent) saying the extra $300 payments should end than saying they should continue (41 percent). Even the White House started to buckle: After President Biden had said there was no connection between the benefits and lagging job numbers in early May, a month later he was stressing they were only temporary. White House press secretary Jen Psaki, meanwhile, called their effect “a really difficult thing to analyze.”

Between late June and early July, 25 states announced they would be ending the program, but after a robust job report last week — with the benefits still in place in most states and no clear data to show a bump in job searches in the states that had already cut them — it appeared the deficiencies of the program might have been overstated.

“It seems like something that was completely misguided and not supported by the facts or the evidence at all,” said Valerie Wilson of the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal think tank. “There were a lot of inaccurate comparisons and conclusions drawn.”

“I think the idea of wanting to cut benefits early is more a political point than one that is justified by the economic data,” Wilson added. “With the latest report, we’re on track for the recovery to remain strong and vibrant, and I just don’t think it’s a very wise decision to do anything to hinder that at this point. Those benefits are important for families and contributing to the demand that is needed for job growth to continue. By cutting those prematurely, you risk cutting the recovery short or at least hindering it.”

Analysts offered numerous other reasons for why spring job growth came in below expectations beyond Americans being paid to sit at home: There were continued fears over the coronavirus, and lack of childcare made it difficult for parents to reenter the workforce. And there was the fact that after a year or more, workers were reconsidering jobs that offered low wages and erratic schedules, as businesses reported success in hiring new workers when they offered higher wages.

A June working paper from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco showed the “moderate disincentive effects of the $600 supplemental payments on job finding rates and by extension small effects of the $300 weekly supplement available during 2021.” But there was also a study from Yale in July 2020 that found that expanded unemployment benefits did not affect employment, and a February report from the JPMorgan Chase Institute echoed those results, saying there was “little evidence that elevated unemployment insurance benefits discouraged people from returning to work.”

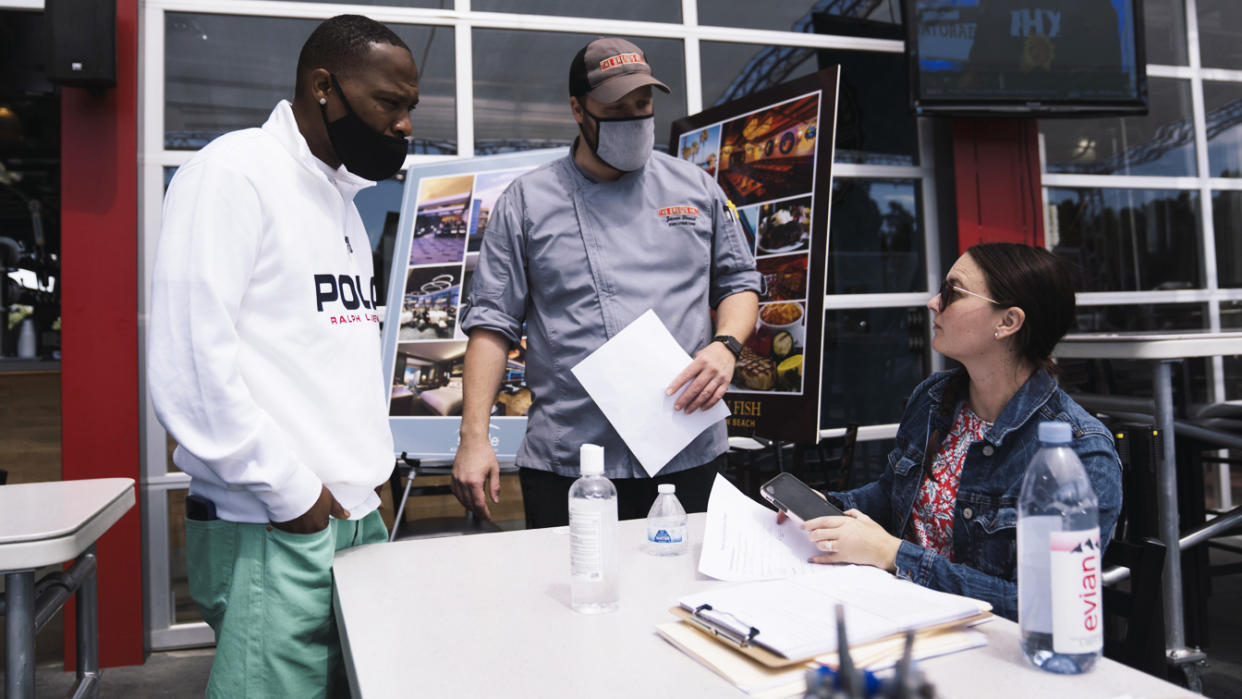

Additionally, a Pew analysis from October 2019 found a labor shortage that predated the pandemic and expanded benefits, noting that “in 39 states, there are more jobs than people looking for them.” The leisure and hospitality industry, often referred to as a prime victim of the expanded benefits, saw the biggest gains in the last several job reports, although total employment in that sector remains well below pre-pandemic levels.

According to data from the job-search site Indeed, states that cut benefits early saw little movement versus those that maintained them. Nick Bunker, an economist for Indeed who’s been following the state-level numbers, told Yahoo News the disappointing job numbers earlier this year were the result of a number of factors, with no single “smoking gun.”

“Looking at job seeker activity state by state, what we saw essentially was no real clear pattern,” Bunker said. “In the data it didn’t look like the roll-off of UI was an obvious and major factor in job seeker activity, at least on Indeed. Once we have a deeper analysis in the months and years ahead, these UI benefits probably did have an impact on job seeking, but it doesn’t seem to be the biggest constraint, it’s not showing up obviously in macro data.”

Bunker noted that Indeed began running surveys of job seekers in late May, and while people mentioned the benefits as a reason for why they were searching less urgently, they weren’t the biggest factor, with concerns over the virus the most common response in addition to childcare and existing financial cushions.

“Another way of looking at it is that UI benefits are having an impact, but maybe they’re working in confluence with other factors,” Bunker said. “Yes, UI makes it easier for some people who are more concerned about the virus to hang back, but even if you took away the benefits there are some people who might return to work quicker, but that’s pushing them into a situation that may not be the best for them at that moment.”

While June’s job report was promising, the economic recovery still has a long way to go, with everything from COVID variants to inflation potentially impeding growth. Still, Biden and the White House celebrated the latest report.

“There’s no question in my mind that enhanced UI benefits have been a tremendous boon — they’ve served precisely their insurance purpose for workers hit by the pandemic,” said Biden administration economic adviser Jared Bernstein on Friday.

____

Read more from Yahoo News: