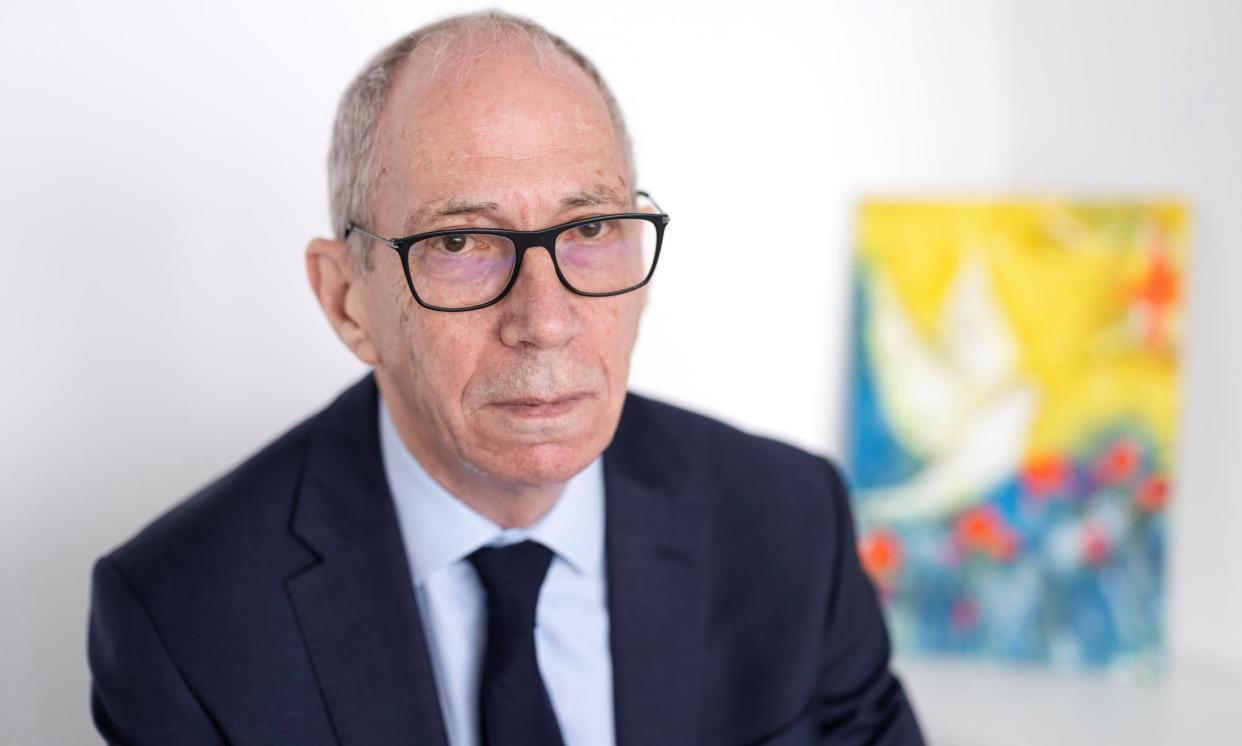

NHS ombudsman Rob Behrens: ‘There are serious issues of concern’

“This has been a chastening experience,” says Rob Behrens. The NHS ombudsman for England is reflecting on his seven years in the role, which end soon, in which he has acted as the arbiter of last resort for people who have exhausted the health service’s complaints system. Chastening? How?

“Dealing with people who have experienced trauma and bereavement as a result of avoidable death in the NHS requires empathy and compassion alongside impartiality and fairness.

“Secondly, confronting the duality of an NHS resourced by brilliant people who kept it going through the Covid pandemic but, at the same time, having to confront a cover-up culture, including the altering of care plans and the disappearance of crucial documents after patients have died and robust denial in the face of documentary evidence,” he says.

Sipping tea from a mug featuring his beloved Manchester City, Behrens is softly spoken. But when asked what he has learned about the NHS, his verdict is tough. “That it’s a very complex organisation, full of brilliant people, from porters to nurses, midwives, clinicians and managers, who have done brilliantly in handling multiple crises: Covid, huge staff shortages, financial pressures, demand, [staff] stress, the frailty of buildings, which makes life very difficult.”

But – and it is a big but – despite the everyday wonders the NHS performs, he has found that “within that brilliant environment there are serious issues of concern, especially about aspects of the culture of the NHS”.

“The detriments that people experience are significant and should not be happening. In significant areas – in maternity care, mental health, avoidable death, sepsis, eating disorders – time and again I’ve come across stories of people who only want the truth about what happened to their loved one and they found it very difficult to get it.

“That’s my job – to get at the truth.”

It is also his job, he adds, to highlight when the NHS makes the same mistake worryingly often, to assess its response when failings are identified and to propose ways of changing things. Medical care is never risk-free. But the key test of a good system, Behrens suggests, is whether lessons are learned after something goes wrong and changes made to avoid a repeat. His experience, based on examining thousands of complaints, is that too often in the NHS that does not happen. And also that far too many staff brave enough to highlight poor practice are then victimised.

By way of illustration he mentions Dr Rosalind Ranson, the former medical director of the NHS on the Isle of Man. She received £3.2m in damages last year after an employment tribunal heard how she had been unfairly dismissed after airing her concerns about the government’s response to Covid-19.

“I’ve had doctors on the phone to me telling me what has happened on too regular a basis over the seven years. They say that they’ve tried to make a complaint, to raise issues about patient safety, and they’ve been warned off. And they have said to me: ‘If I continue with this, my career will be over.’ Good clinicians have lost their careers as a result of the way that happens.”

Related: Letby inquiry must also examine NHS ‘cover-up culture’, says ombudsman

The Countess of Chester hospital’s decision to ignore concerns paediatricians raised about Lucy Letby – at one point they forced the doctors to apologise to her for their suspicions – illustrates his point.

He refers, too, to the rotten culture and scandalous treatment of whistleblowing staff by University Hospitals Birmingham (UHB) NHS trust, which the BBC’s Newsnight exposed in 2022. “The thing that shocked me the most about UHB is that management dealt with reports about patient safety by sending people to the General Medical Council and threatening them that they were misbehaving. That is disgraceful,” says Behrens.

Over a decade, UHB reported no fewer than 26 of its medics to the GMC, which can suspend or strike off doctors found guilty of wrongdoing. UHB referred eye surgeon Tristan Reuser after he warned there were too few nurses to ensure the safety of operations. Reuser said that in his experience whistleblowers at the trust suffered “victimisation and retribution using GMC referrals. If you criticise senior management, they’ll have you.”

The GMC took no action against any of the 26 doctors. But it did issue a formal warning to Dr David Rosser, who at the time was the trust’s medical director and later became its chief executive, for not telling them that Reuser was a whistleblower. Rosser later left the trust. An employment tribunal later found Reuser had been wrongly dismissed.

An ombudsman should be forensic, fair and impartial. But, Behrens says, investigations into medical negligence and hospitals’ efforts to downplay or bury the truth, and helping families whose loss has been compounded by secrecy to get the facts, can be emotionally taxing. Some have left him angry at what he has found. He cites Bristol children’s hospital’s refusal to tell Ally Condon for seven years exactly why his eight-week-old son Ben died in April 2015. Staff failed to give him antibiotics fast enough to thwart a virus, it later emerged.

“They withheld test results, they told us tests, which were never taken, were negative, they removed documents from the medical notes – it’s endless,” Ally Condon said.

Behrens’s seven years in his post have seen action taken to improve patient safety: the imminent rollout of Martha’s rule , giving patients and relatives the right to demand a second opinion if they are unhappy with someone’s care; the creation of the Health Services Safety Investigations Body; and the NHS getting its first ever patient safety commissioner, adding to an array of regulators that also includes the Care Quality Commission and GMC.

But, the ombudsman says, there are now “too many regulators in the health service – too many bodies doing roughly the same thing – [and] they’re not sufficiently joined up, which means that decisive action which should be taken isn’t taken, because ministers aren’t getting one voice about what should happen.” Legislation is needed to make things less confusing, he adds.

He wants his successor to have their “own initiative powers” – the ability to investigate things even when no formal complaint has been made, as sometimes scandals unfold in the NHS with insiders knowing but nothing being done, such as the death of mental health patients. Too often, he adds, “the people least likely to complain are the ones who most need the ombudsman – people with mental health challenges, who are elderly or are from ethnic minority backgrounds or are poor.”

Ministers have told him that, in effect, that power would lead to the ombudsman poking their nose into too many things and generating an even greater workload. Complaints against the NHS have already risen by 15-20% since Covid. The experience of his counterparts elsewhere who already have that right, including Wales and Northern Ireland, does not bear out that fear, he counters.

How can the “cover-up culture” be ended? “First of all, you have to recognise that it exists and secondly you have to make leaders accountable for how the culture operates,” he says. Ministers, NHS bosses and the boards of NHS trusts need to be much more pro-active, he adds.

Behrens, who retires at the end of the month, comes back time and again to the anguish families have experienced when trying, often for years, to find out what happened to their loved one. He quotes Nye Bevan’s words from his book In Place of Fear that “silent pain evokes no response” to capture how that suffering, despite being worryingly common, is not leading to the change in culture needed. “In modern parlance, if you don’t speak up, injustice and service failure continue unchanged,” he adds.

He is referring to whistleblowers, many of whom pay a heavy price for their candour. But his words apply equally to him, too, given his rigour, independence and readiness to speak truth to power.

Is care safer and the NHS more accountable than when he started? He pauses. “There are still too many examples of care not being safe and health trusts being too slow to deal with it. It shows we haven’t got to the root of the problem yet. My successor will have big issues to confront.”