National Cathedral’s removal of Confederate stained glass reflects Washington’s complicated racial past

For nearly 70 years, the images of Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson loomed from stained-glass panels in the National Cathedral, a Washington, D.C., landmark where funerals for presidents and other dignitaries are often held and important events commemorated.

The windows were taken down in 2017, shortly after an outburst of racist violence in Charlottesville, Va., intended to stop the removal of a Lee statue there.

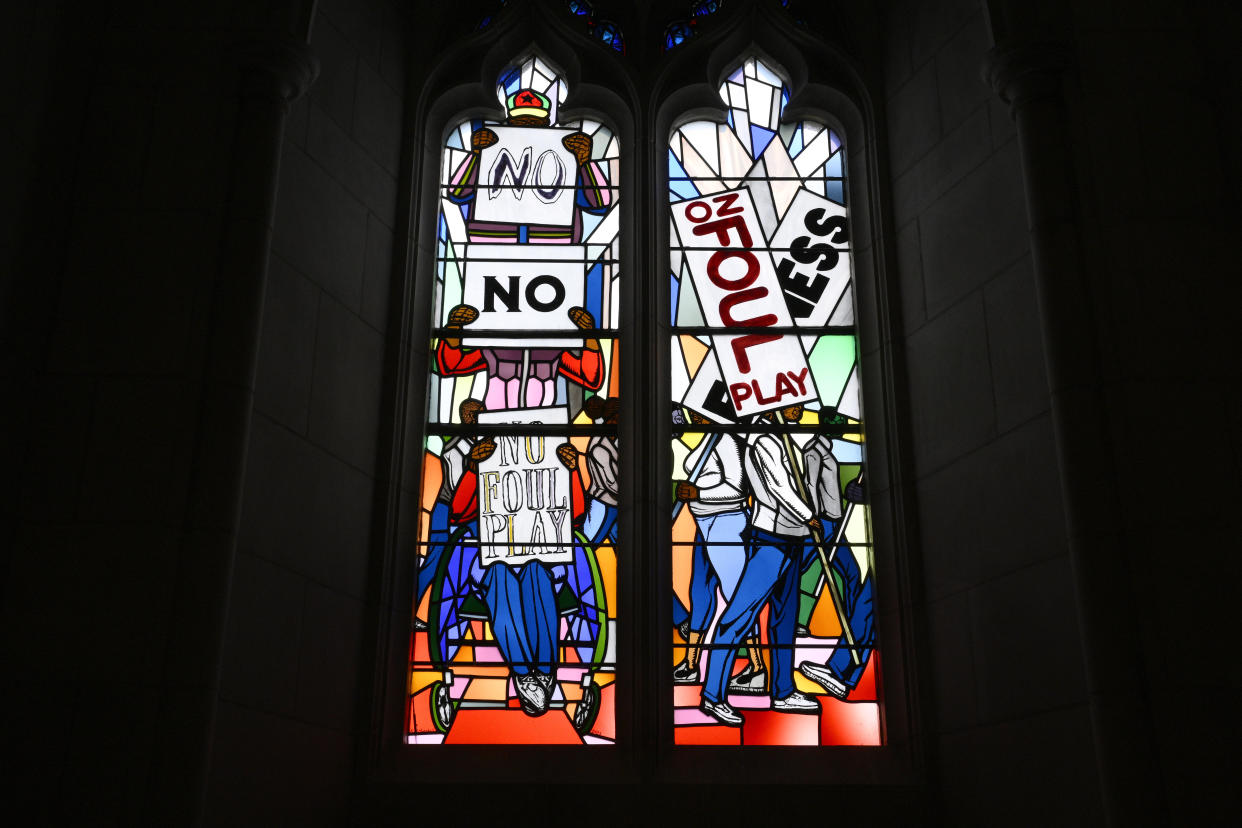

But it took another six years for the windows to be replaced. Over the weekend, Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson — the first Black woman to sit on the high court — read from Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail” as new windows celebrating the fight for civil rights and racial justice were unveiled.

The saga of the Confederate windows sheds light on Washington’s complex past as a majority-Black city with a legacy of racism and segregation that extends far beyond stained glass.

Read more on Yahoo News:Stained glass window shows Jesus Christ with dark skin, stirring questions about race in New England, from the Associated Press

The ‘Lost Cause’ rises

The removed panels honoring Lee and Jackson — which include a depiction of the Confederate flag — were donated to the cathedral by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1953. Statues and memorials to the Confederacy proliferated in the first half of the 20th century. These memorials disingenuously celebrated the Confederacy as a noble “Lost Cause” while entirely ignoring the South’s centuries-long reliance on slavery, which culminated in the Civil War.

The United Daughters of the Confederacy were central in spreading the Lost Cause mythology. “Their goal, in all the work that they did, was to prepare future generations of white Southerners to respect and defend the principles of the Confederacy,” historian Karen Cox told FiveThirtyEight.

As the push for civil rights gained momentum throughout the late 1950s and early ’60s, Confederate memorials stood out ever more starkly as sites of white resistance to racial progress.

Read more on Yahoo News:When Confederate-glorifying monuments went up in the South, voting in Black areas went down, from the Conversation

D.C.’s complicated legacy

Washington is situated below the Mason-Dixon line, which separated free and slave-holding states in the 19th century, and was a decidedly Southern city for much of its early history. Today, the city is closely integrated into the Northeastern corridor that stretches north to Boston.

Abraham Lincoln abolished slavery in the District of Columbia in 1862, and many Black people flocked there in the decades after the Civil War, seeking government jobs that afforded thousands of families passage into the middle class.

That door was slammed shut by Woodrow Wilson, whose progressive beliefs disguised an underlying racial contempt. Wilson “promptly filled his administration with segregationists who worked diligently to segregate as much of the work force as they could,” Brent Staples wrote in a 2017 New York Times history of race relations in Washington. “Highly paid black workers were driven out or confined to lower-paying jobs, undercutting the nascent black middle class. Many black workers were barred from offices, bathrooms and lunch tables that they once had shared with white co-workers.”

It was not until 1973 that Washington finally won home rule and was allowed to elect its own mayor. Congress had been reluctant to hand over control of the district in large part because of its majority-Black citizenship. Even today, Congress retains unprecedented power to intervene in Washington’s affairs.

Read more on Yahoo News: Don’t erase Woodrow Wilson. Expose him.

A reckoning in Washington

In 2009, the nation elected its first Black president, Barack Obama, whose presidency was perceived by some as the start of a “post-racial” era in the country. Washington changed, too, absorbing some of New York’s cool and attracting young new residents. The district lost its Black majority in 2011.

The election of Donald Trump, however, made clear that no “post-racial” moment had arrived. Protests against his administration erupted at once, and Washington often had the grim feel of a city under siege.

The tensions that had been building throughout the Obama and Trump administrations, and that had been exacerbated by the more recent isolation of the coronavirus pandemic, exploded in the summer of 2020. Protesters toppled the statue of Gen. Albert Pike, the only outdoor Confederate monument in Washington, which led to an angry outburst from Trump. He made defending Confederate statuary a central premise of his losing reelection campaign.

The following year, the House voted to remove statues commemorating Confederates and enslavers.

Read more on Yahoo News:Democrats reintroduce legislation to remove remaining Confederate statues in U.S. Capitol, from WSOC-TV

‘Work to be done’

“There is a lot of work yet to be done,” the National Cathedral’s dean, Randolph Hollerith, said as the new civil-rights-themed windows were installed on Saturday.

Washington remains a deeply segregated city, with profound disparities in wealth, educational outcomes and access to parks. But it is also, finally, a city free of the Confederacy’s legacy. Across the Potomac River, however, there is a memorial to Confederate soldiers at the Arlington National Cemetery. A panel recently recommended its removal.

Read more on Yahoo News: Confederate general's remains moved to Virginia hometown, from the Associated Press