The minotaur beetle – a down-to-earth devourer of dung

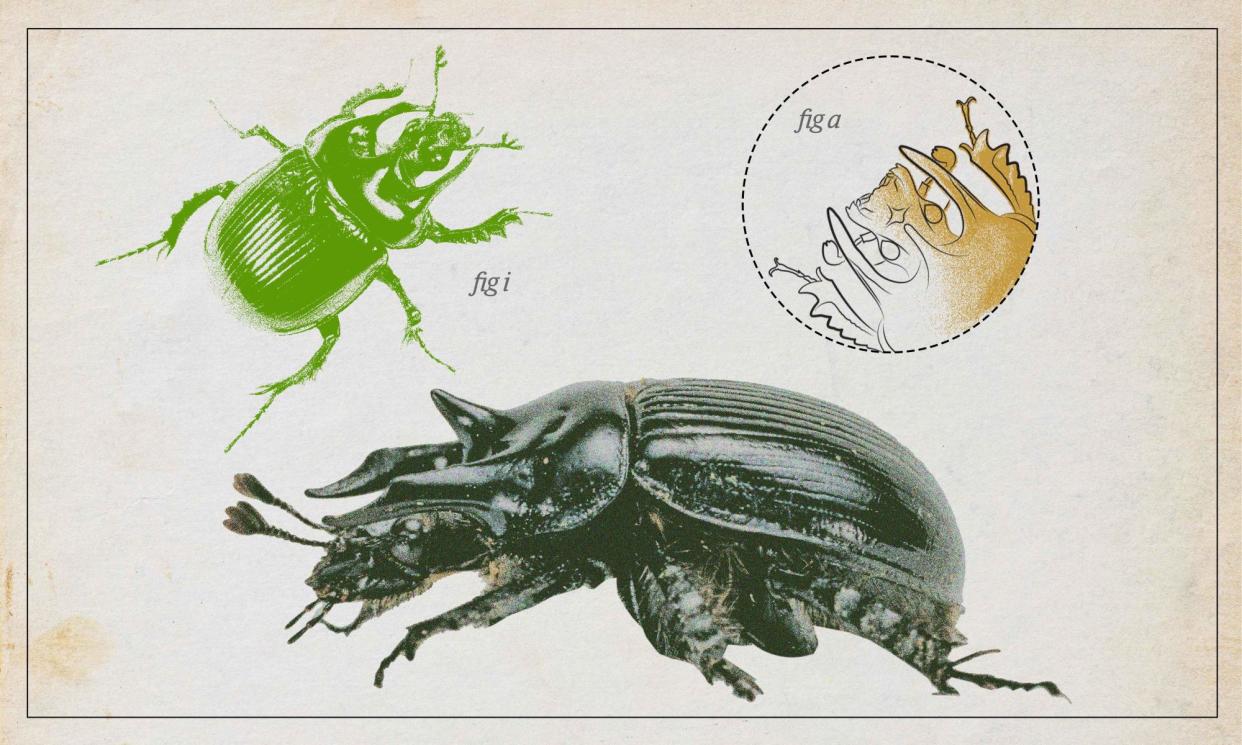

If you’re a what-have-they-ever-done-for-us? sort of voter, you will be won over by the minotaur beetle. It’s as spectacular as any beetle, the shiny black male sporting three bullish horns on their thorax. But the minotaur is also one of that great hidden army of invertebrates who keep our planet functioning – clean and fertile – without us even knowing.

The minotaur is a dung beetle and roams across grassland and heathland at night devouring mammalian droppings.

There are more than 5,000 species of dung beetles across the world and they are a crucial “keystone” species because they bury dung in the ground to feed their young – cleaning up, recycling nutrients, fertilising the soil and helping to disperse seeds. One study estimates the value of dung beetles clearing British pastures and fertilising soils to be £367m a year.

Unfortunately, the dung beetle population around the world has plummeted since the intensification of agriculture. Livestock are given so much anti-worm and anti-parasite treatment that these are excreted in dung, creating a toxic soup that is fatal for dung beetles and many other dung-feeding invertebrates. In France, conservationists have begun reintroducing dung beetles to boost rewilding projects.

The minotaur beetle is scarce in Britain and extremely rare farther north. It grows to only 2cm but the male packs a punch with its short central horn and two long ones either side. These fearsome tools are deployed to defend burrows and intimidate or spar with other males before mating. The female, once paired, lays about 20 eggs at the end of a labyrinth of tunnels up to 1.5 metres below ground.

Rather sweetly, the minotaur couple then work together to provision their young with dung food. The male mostly labours above ground, collecting dung pellets, dragging them backwards and inserting them into the burrow. The female then shapes them into long tubes, which fill the brood chambers. Other dung beetle species also work together to roll balls of dung to their nests, unusually cooperating despite not knowing their final destination – so rather like human life, then.

Each minotaur larva is left with enough food to develop rapidly, while the exhausted parents die in midsummer. The new generation emerge in the autumn, usually after a spell of rain, and their virtuous cycle continues.

So if you’re drawn to aggressive-looking alpha males who actually embrace equality of the sexes and hard work, and a species where both males and females are practical, down-to-earth and loyal, vote now – vote minotaur!

Welcome to the Guardian’s UK invertebrate of the year competition. Every day between 2 April and 12 April we’ll be profiling one of the incredible invertebrates that live in and around the UK. Let us know which invertebrates you think we should be including here. And at midnight on Friday 12 April, voting will open to decide which is our favourite invertebrate – for now – with the winner to be announced on Monday 15 April.