He led Brazil’s Black sailors in mutiny to resist abuse. A hundred years later he may get justice

He was a Black Brazilian sailor who led an unprecedented mutiny against abuse by white officers, and helped end flogging in the country’s navy – only to be imprisoned, persecuted and die in poverty.

For five days in 1910, João Cândido Felisberto held Rio de Janeiro hostage under the guns of the Brazilian fleet, in an uprising known as the Revolt of the Lash.

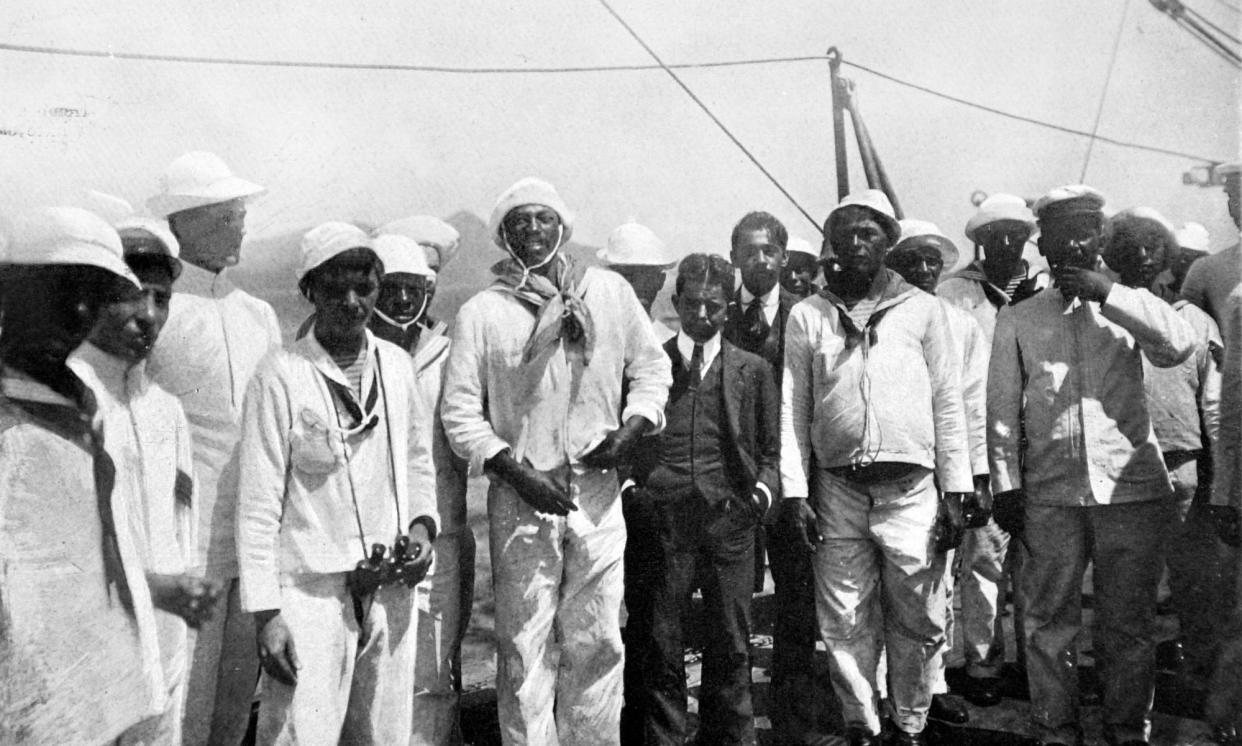

Thousands of Black sailors, some of whom had been radicalized when they were sent for training in Newcastle upon Tyne, joined the mutiny, which took place just 22 years after Brazil abolished slavery.

The mutineers achieved their main goal – the end of corporal punishment – but the uprising was swiftly crushed, and hundreds were imprisoned.

Cândido, once dubbed the Black Admiral, was jailed and eventually cashiered from the navy. Once free, his efforts to find work were blocked by the military, and he was forced to scrape a living as a dock worker.

Now, however, a new effort has been launched to achieve a measure of posthumous justice. Julio Araujo, a federal prosecutor in Rio, has petitioned Brazil’s government to make reparation for the treatment he endured.

“The Brazilian state played an active role in the surveilling, persecuting and controlling the life and the legacy of João Cândido,” wrote Araujo, who has also called for Cândido’s descendants to receive financial compensation.

Related: Brazil slave trafficker’s links to top bank spark debate over reparations

Born in 1880 to enslaved parents, Cândido joined the Brazilian navy at 15, sailing to ports across South America and Europe.

At the time, the force was still in effect segregated, with Black or mixed-race sailors and mostly white officers, who maintained discipline with a heavy dose of corporal punishment. Other navies had abolished the use of “disciplinary” beatings, but even minor infractions on Brazil’s fleet were met by beatings with whips, sticks and rope, sometimes “enhanced” with nails.

“The sailors were also overburdened with work and treated like slaves,” said the historian Álvaro Nascimento, professor at the Federal Rural University of Rio and author of a book about Cândido.

But Brazilian sailors were exposed to a strain of transatlantic radicalism by contact with their British counterparts. In 1909, the Brazilian government bought two dreadnought battleships from British shipbuilders, and hundreds of sailors were sent to Newcastle, where they spent months training – and also picking up new political ideas.

“They were in touch with English sailors, who had a different social consciousness. Ideas about strikes, anarcho-syndicalism, and the workers’ struggle started circulating among Brazilian sailors,” said historian Silvia Capanema, professor at Université Sorbonne Paris Nord, who has also written about Cândido.

The sailors in the UK organised “rebel committees”, and stayed in touch with sympathizers back in Rio, then the Brazilian capital. When the two battleships returned to Brazil in early 1910, the two groups started plotting how to end corporal punishment for good.

The immediate catalyst for the revolt came on 21 November 1910 when the crew of the dreadnought Minas Gerais was forced to witness the flogging of a crewman who was given 350 lashes.

The following night, mutineers seized the Minas Gerais and later the other new battleship, São Paulo.

Six officers and six sailors were killed. Warning shells were fired, one of them killing two children on the hills above Rio (the sailors would later pool their resources to compensate the children’s families).

In a telegram to then-president Hermes da Fonseca, the mutineers demanded the immediate end of corporal punishment; for good measure, they also trained their guns on the Catete Palace, which housed Fonseca’s offices.

The uprising ended on 26 November after the president promised to ban corporal punishment and grant amnesty to all those involved. But just three days later, Fonseca authorized the navy to summarily dismiss any military personnel shown to be “refractory to discipline”.

A new uprising erupted the following month, but it was quickly crushed, with the arrest of hundreds. João Cândido didn’t take part but was identified as a ringleader and spent two years behind bars.

He was never convicted, but faced years of persecution, said Capanema. “The navy didn’t allow him to stay or work anywhere else. They even withheld his documents at some point, so he couldn’t apply for any new job.” Cândido died in 1969 aged 89.

In the petition he filed last month, Araujo accused the navy of the “incessant persecution” of the Black Admiral. He addressed his petition to an amnesty commission attached to the human rights ministry, which earlier this month issued Brazil’s first-ever apology for the torture and persecution of Indigenous people during the military dictatorship.

Araujo also called on members of congress to approve a bill recognising João Cândido as a Hero of the Nation. After being approved by the senate in 2021, the bill is currently stalled in the lower house, reportedly due to the navy’s resistance.

Thiago André, a former naval sergeant who left the force to host the Black history podcast História Preta, said that while much had changed since Cândido’s revolt, many things had remained the same – such as the inequality between officers and lower-rank personnel.

But he cautioned that such issues were not restricted to the forces. “When someone says to me, ‘The navy is very racist,’ I reply, ‘This is Brazil. Brazil is very racist’,” said André.