Kenya’s ‘blood desert’: can walking donor banks and drones help more patients survive?

In his small cubicle in Lodwar County referral hospital in north-west Kenya, Edward Mutebi, the technician in charge of the hospital’s blood bank, greets a nurse from the maternity ward. “We want more blood,” the nurse says. “The previous allocation was not enough.”

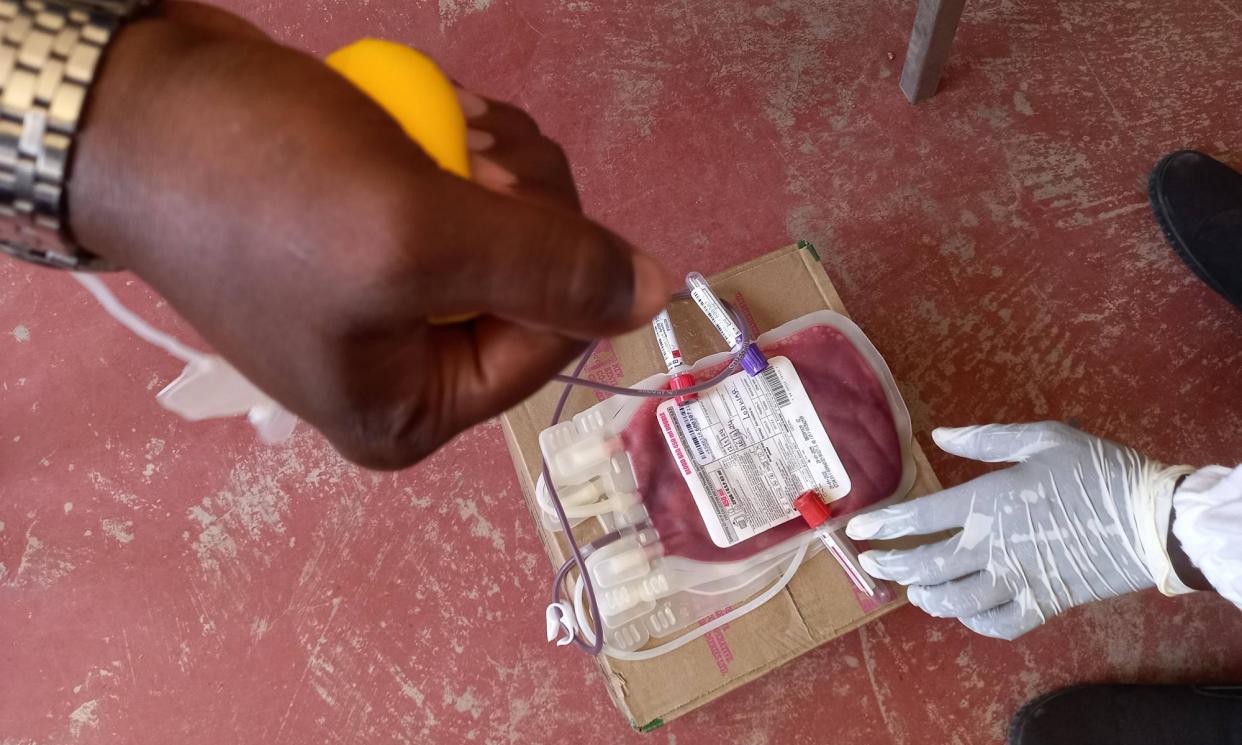

Mutebi dashes into an adjacent room and hands the nurse a pack of blood from a freezer, leaving the paperwork for later. Back at the maternity ward, it is a race against time as doctors try to stabilise a mother who has lost too much blood during delivery. Her haemoglobin level is dangerously low.

“I think the question about why blood is always needed here has been answered,” says an exasperated Mutebi, who has been working at the hospital blood bank for 17 years. “I hope the amount of blood units we have issued [to the new mother] are all she needs because we are short of blood. We are always running short. I had 15 units of the O+ type when I came in this morning. I am now down to three.”

Mutebi receives about 20 requests for blood a day from doctors at Lodwar hospital – more than he can provide. “I can only manage up to 15, yet this hospital is supposed to serve the blood needs of other facilities within Turkana county.”

More than 400 patients visit the 270-bed hospital every day. Most are referred from 282 smaller medical facilities within Turkana county, but it is not uncommon for patients to come from as far as South Sudan and Ethiopia.

Turkana is the second-largest county in Kenya, covering 13% of the country. In its desert conditions – made worse by the climate crisis – temperatures can soar to 40C, with many living in extreme poverty and often reliant on food aid.

During the recent four-year drought that affected the Horn of Africa, the largely pastoralist Turkana community lost its livestock, leaving families to survive without food for weeks, forced to subsist on wild fruit. Children and elderly people are the most affected; many become anaemic and require blood transfusions.

Globally there is an annual deficit of more than 100m blood units in low and middle-income countries, resulting in millions of preventable deaths, according to the Blood Desert Coalition, an international group of doctors, researchers, patient advocates and policymakers set up in 2023. It says every low and middle-income country has “blood deserts”, which it defines as “geographical regions where essential clinical demand for blood components cannot be met at the point of care in a timely and affordable manner, in at least 75% of cases where transfusion is needed”.

Turkana is one such blood desert.

“Many of the referrals are emergency cases that require blood,” says Epem Esekon, the director and chief executive of Lodwar County referral hospital. “We have a volatile border between Uganda and South Sudan and pockets of insecurity in several areas of northern Kenya. Some people come here having lost a lot of blood due to gunshot wounds. We are the main referral hospital for Kakuma refugee camp with 250,000 refugees. Then we have over 400 cases of malaria every month, many of whom become anaemic and in need of transfusions. Here, blood runs out in 40 out of every 126 days.”

Women are usually reluctant to give blood, yet they are the ones who need it most

The Kenya Tissue and Transplant Authority (KTTA), the government body that oversees blood transfusion services, says the country requires 510,444 units of blood annually, but collects only 300,000.

To address the need for blood in Turkana, Mutebi and his team periodically set up camp in communitiy churches, mosques or colleges to raise awareness of blood donation. The day before the Guardian’s visit, Mutebi had mobilised dozens of students from a local college to donate blood. “Only nine people sat on those benches, mostly men,” he says. “Women are usually reluctant to give blood, yet they are the ones who need it most.”

Testing blood once it has been collected is a further challenge. In Kenya, there are just six centres where donated blood is screened for transfusion-transmissible infections (TTIs), especially HIV, hepatitis B, C and syphilis. For Turkana, the nearest centre is located in the agricultural town of Eldoret, 360km (220 miles) south of Lodwar. A dusk-to-dawn curfew around the volatile town of Kainuk, about 170km south of Lodwar, means blood samples cannot be transported to or from Eldoret in late afternoon, further disrupting emergency operations in Lodwar.

“It is eight hours to Eldoret if you leave in the morning,” says Esekon. “Then eight hours back. Sometimes, we may not have our own transport and have to rely on matatus [Kenya’s public-transport vans] to take the samples to Eldoret and back. At times I have used money out of my own pocket for that purpose.”

For doctors like Juma Odhiambo, an obstetrician-gynaecologist who deals with postpartum emergencies at Lodwar, the 24 to 48-hour turnaround time is nerve-racking.

“In a remote area without easily accessible medical centres, we have many home births that backfire and women who come here when they are critically ill. There is a low uptake of contraceptives in Turkana and 50% of girls start giving birth at 16 years. Due to poor nutrition, they are highly anaemic and in need of blood during delivery – that is, if they make it here,” says Odhiambo. “We recently lost a mother in her 30s while she was delivering her eighth child because she arrived when it was too late.”

Medical personnel in Lodwar hope the national government will approve the introduction of “walking blood banks”, where blood from registered donors is screened using rapid diagnostic testing (RDT).

Walking blood banks have been in use for decades in emergency situations, such as war or natural disasters, when banked blood is not available. The system relies on using pre-screened donors who can be called upon at short notice to donate blood that is tested on the spot. The blood is typically transfused as whole blood. Last year, in partnership with the Blood Desert Coalition, Lodwar hospital started the first large-scale walking blood bank trial in a civilian setting.

The group tested more than 800 blood samples collected at Lodwar to determine the efficacy of RDTs. After comparing the RTD results with Kenya’s national screening procedure, researchers found out the rate of TTIs in the donor pool was relatively low at 5.4%, and that the RDT results matched the national standard in 99.2% of cases.

Related: Dramatic rise in women and girls being cut, new FGM data reveals

Dr Nakul Raykar, an assistant professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and the chair of the Blood Desert Coalition, stresses that walking blood banks are not a replacement for traditional blood banking in low and middle-income countries, but “they can serve as an emergency backup measure when [laboratory-screened] banked blood is unavailable”.

This year the coalition will launch studies of two other methods to address blood shortages: auto-transfusion and drones. The former uses a device that collects a patient’s own blood during surgery, cleans it and transfuses it back. Such devices are already in use in Lodwar, and other hospitals in Nairobi, Kilifi and Kisumu. Studies on drone technology will be run in Kenya and India, testing technology such as Zipline, a California-based company that is established in Rwanda, where it has been used to deliver 20% of the country’s blood supply outside the capital, Kigali.

However, it is walking blood banks that hold the greatest potential to save lives. The research group hopes to roll out the strategy in Turkana from this autumn, but first it has to convince the KTTA that RDTs are sensitive enough.

The KTTA said in a statement: “The matter of [RDT] in blood-transfusion services, especially sub-Saharan Africa is not recommended. According to the World Health Organization’s blood safety programme guidance, TTI-testing algorithms in countries with high endemicity of HIV, hepatitis B, C and syphilis must consider highly sensitive test methods to prevent post-transfusion transmission of TTIs.

Policies on blood are made in Nairobi, while it is the doctor at Lodwar hospital who looks on as a mother dies while waiting for test results

“The fear of RDTs stems from their [lack of sensitivity] in detecting TTIs, considering the high prevalence of these diseases in Kenya. The Turkana region is highly endemic for HIV and hepatitis B infection therefore RDTs will plough back on the gains already made [to eradicate or minimise the dangers posed by TTIs].”

But Raykar says a representative from KTTA has visited Lodwar, met the study team and observed the trial. He believes that when the trial data showing 99.2% efficacy is shared with the central KTTA team they will reconsider.

Dr Gilchrist Lokoel, the medical director for Turkana county, says without the use of emergency measures such as walking blood banks, doctors are forced to make tough choices between blood safety and the need to save a dying patient.

“Policies on blood are made in Nairobi, while it is the doctor at Lodwar hospital who looks on as a mother dies while waiting three days for blood test results to be delivered from Eldoret,” he says. “Can you imagine telling a heavily bleeding mother who has crossed the crocodile-infested Lake Turkana in a rickety canoe to wait that long because policy demands that she waits? The government must heed the call of science.”