Irvo Otieno's death is the latest example of how police are 'failing people' during mental health crises, advocates say

The death of 28-year-old Irvo Otieno, a Black man who died in police custody at a mental health facility in Henrico, Va., earlier this month, has sparked concern for police responses to mental health incidents.

The surveillance footage showing the final moments of Otieno's life was released to the public Tuesday, after it had been obtained by the Washington Post. In the video, Otieno, handcuffed and with leg irons on, appeared helpless, while officers held him down for more than 10 minutes.

"My son was treated like a dog. Worse than a dog. My son was tortured," Caroline Ouko, Otieno's mother, said at a press conference after she saw the footage.

According to the chief medical examiner's preliminary report, Otieno died from asphyxiation on March 6 during the encounter with authorities. “Mental illness should not be your ticket to death. I don’t understand how all the systems failed him,” Ouko said.

Ten people were charged with second-degree murder in Otieno’s death, including seven Henrico County deputies and three hospital employees. On Monday, Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin, a Republican, described Otieno’s death as “heart-wrenching” and said the public mental health system is overdue for changes.

"What we have is a system that is built today and overwhelmed today with the in-crisis moment, and where we are so lacking is pre-crisis services,” Youngkin told reporters. “We also can just see the heart-wrenching nature of the challenges in our behavioral health system and why I think it is so important that we press forward with aggressive transformation of that system.”

'Policing is failing' mental health crises

A 2020 study by the Center for American Progress found that 21% to 38% of 911 calls made from eight cities involved behavioral health crises, substance use, homelessness, quality-of-life concerns and community conflicts.The report also estimated that between 33% and 68% of police calls don’t need an armed officer.

“Until America realizes that policing is failing people going through a mental health crisis, they will be able to continue to create more hashtags,” Zellie Thomas, lead organizer of the Black Lives Matter chapter in Paterson N.J., told Yahoo News.

Otieno is just the latest “hashtag.” Only three days before he died, 31-year-old Najee Seabrooks was shot and killed by police in Paterson after he called 911 during a mental health crisis.

“That should be alarming to people to realize that we are not handling mental health crises with support, care and compassion. We're handling it with trauma, violence and even fatalities,” Thomas said.

Experts say the intersection between mental health and policing can be deadly, especially for Black Americans. Black people are 2.9 times as likely as white people to be killed by police in the U.S., according to Mapping Police Violence, a nonprofit group that tracks police shootings.

“Data shows that these harms are disproportionately shouldered by Black communities and other communities of color,” Daniela Gilbert, director of the Redefining Public Safety initiative at the Vera Institute in Brooklyn, N.Y., told Yahoo News. “I think the issue is with the criminal legal system overall, and so in the context of [mental health] calls, that disparity is also apparent.”

While minorities are affected at a higher rate by the lack of mental health resources in the criminal justice system, Zack Stoycoff, the executive director of Healthy Minds Policy Initiative, a mental-health-policy think tank, calls this an issue that ultimately affects everyone.

“The failure of the mental health system is impacting people who have mental health issues,” Stoycoff said. "During the pandemic, about 1 out of 2 of us had some sort of diagnosable mental health issue."

Responses that don’t involve police

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, 1 in 5 American adults is living with a mental illness.

“Mental-health-related events had increased by 60% over the past five years,” Susanna Every-Palmer, head of the department of psychological medicine at the University of Otago, Wellington, in New Zealand, told Yahoo News.

On March 18, Every-Palmer and other researchers released findings from a study that examined the frontline response to mental health crises, summing it up as “An accident waiting to happen.”

The study included data from 57 police officers, 29 paramedics and 33 health care professionals in New Zealand. But Every-Palmer says that while the study was completed in that country, the situation is typical worldwide.

The study found that “police officers were spending lots of their working time responding to 911 calls about mental health crises. They said this was increasing, and it was substantial, [and] some described it as the worst part of their job,” Palmer said. “They said it could be traumatizing for the individuals in distress, and sometimes for the officers as well.”

Is police training enough? Experts say the last thing a person with a mental illness wants to see during a crisis is a badge and a gun.

“Even when officers are trained in de-escalation, the presence of armed responders can intensify feelings of distress,” Gilbert said.

In over 2,700 communities across the country, officers receive Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training, which aims to improve the encounters between officers and people suffering mental health crises. Some say this is not enough.

“CIT is a stopgap measure,” Stoycoff said. “And we call it a stopgap measure because it's not about treatment, it is about training officers to appropriately de-escalate a mental health crisis.”

In a 2020 study, more than 55% of those surveyed said they supported a first responder agency that would respond to issues that don’t require a police presence.

According to the Vera Institute, at least 30 programs nationwide dispatch civilian crisis responders to 911 calls.

In New Jersey, state officials have created a co-responder model known as ARRIVE Together — which stands for Alternative Responses to Reduce Instances of Violence and Escalation — to respond to emergency calls that need more than just a police presence.

“In calls involving emotional distress or mental health, the officer or the team that's sent out is a plainclothes officer in an unmarked car, with a mental health professional,” Matthew Platkin, the state’s attorney general, told Yahoo News.

So far, the program is located in over 11 counties in New Jersey and has helped nearly 350 people, but the program does not exist in Paterson, where Seabrooks was killed earlier this month.

“We like to consider ourselves a national model, [but that] doesn't mean we're perfect. I think we have a long way to go and a lot of work left to do, and I'm certainly committed to seeing ARRIVE in every one of our communities,” Platkin said.

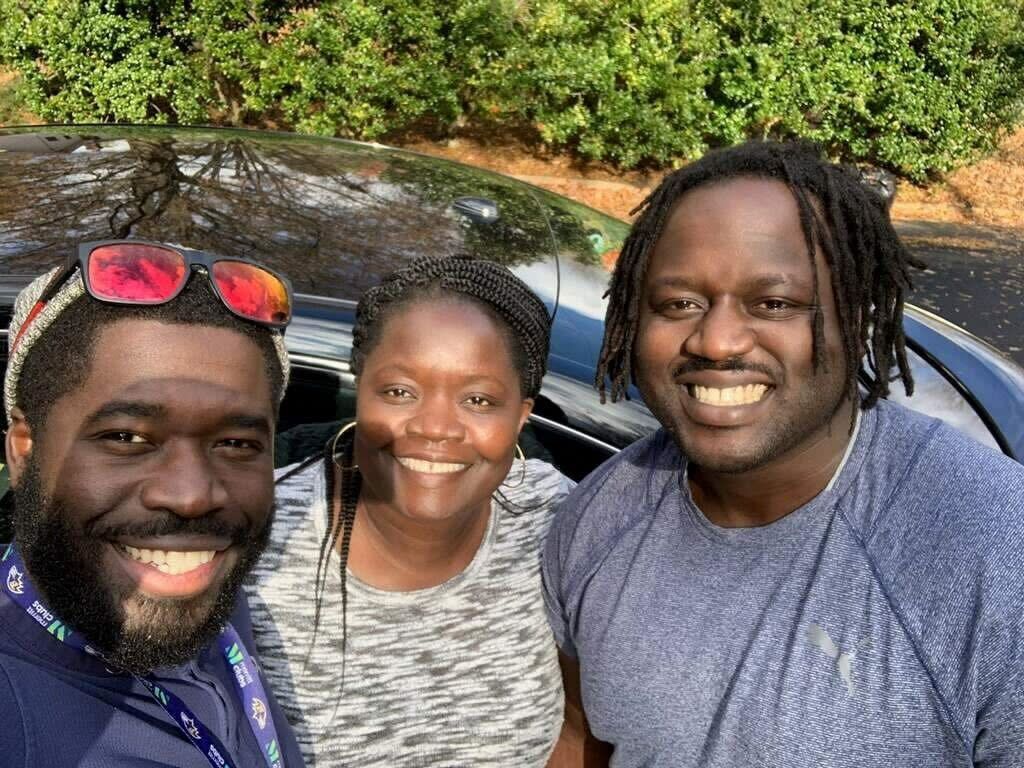

Cover thumbnail photo illustration: Yahoo News; photos: Ben Crump Law via Reuters; Dinwiddie County Commonwealth's Attorney's Office