Irish referendum fiasco puts future of lauded citizens’ assemblies in doubt

When Ireland shattered its history of social conservatism by passing a 2015 referendum on same-sex marriage and a 2018 referendum on abortion, progressives credited its citizens’ assembly.

Ninety-nine randomly selected people, who are brought together to debate a specific issue, had weighed evidence from experts and issued policy recommendations that emboldened the political establishment, and voters, to make audacious leaps.

Governments and campaigners around the world hailed Ireland as a model for how to tackle divisive issues and a modern incarnation of the concept of deliberative democracy that dated back to ancient Athens.

Related: Citizens’ assemblies: are they the future of democracy?

A debacle over twin failed referendums, however, widely seen as the last straw for the man who called them, Leo Varadkar, has now put a question mark over the future of Irish citizens’ assemblies.

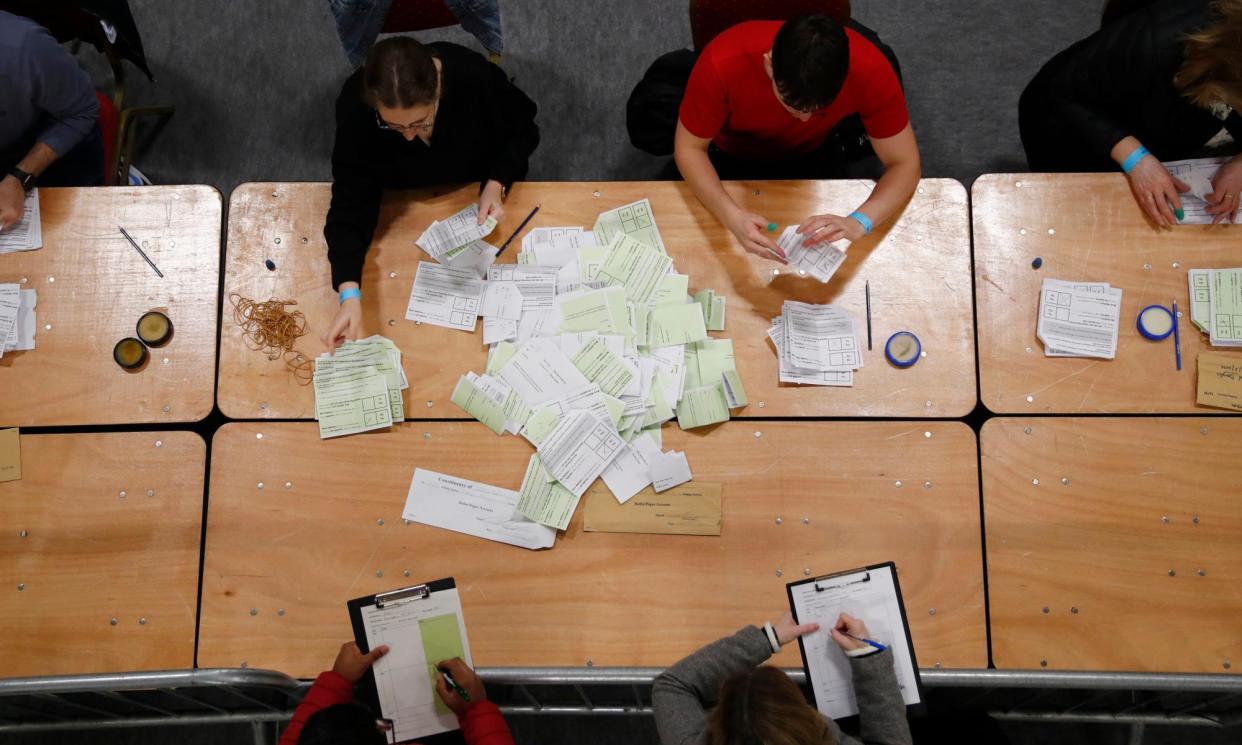

Voters on 8 March overwhelmingly rejected proposals to reword part of Ireland’s 1937 constitution. Asked to widen the definition of family to include “durable relationships”, 67% voted no. Asked to replace a reference to women in the home with a new provision recognising the role of carers, 74% voted no. Turnout was 44%.

The crushing margins chastened the government, opposition parties and advocacy groups that had campaigned for yes votes – and put scrutiny on the citizens’ assembly that had recommended the referendums.

“There is a danger that citizens’ assemblies have now become a part of the policymaking system in Ireland that supports the various agendas of lobby groups,” said Eoin O’Malley, a Dublin City University (DCU) politics professor.

In 2011 O’Malley was part of a group of academics who set up We the Citizens, a precursor to citizens’ assemblies, but he now believes that state-funded non-governmental organisations have “captured” the process, leading in some cases to unrepresentative deliberations and unwise recommendations.

“In certain policies NGOs do tend to set the agenda,” he said.

Assemblies could stimulate productive debate but were not necessarily representative, said O’Malley. People who agreed to spend weekends discussing arcane topics with strangers often had strong, preconceived views, while assembly chairs, who were civil servants, could shape outcomes through selection of experts, he said.

One government source said there was no appetite for further attempts at constitutional change before the next general election and that faith in assemblies had been eroded.

However, many analysts blame last week’s fiasco not on the assembly that recommended the referendums but on the ruling coalition for diluting the proposals in a way that fractured progressive support and confused many voters, and for running a rushed, lacklustre campaign.

Una Mullally wrote in the Irish Times: “Citizens’ assemblies are democratic, detail-orientated, and have proven to accurately reflect the desires of the broader public. The government arrogantly went for different wording, ignoring the outcomes of processes pointing them in the right direction.”

David Farrell, a University College Dublin politics professor who has advised on citizens’ assemblies in Ireland, Belgium and the UK, said last week’s referendums had undermined the assembly’s work. “To produce a wording that doesn’t reflect what was recommended, what’s the point?”

Dozens of recommendations from other assemblies have been ignored or rejected over the past decade, a reality masked by the success of the same-sex marriage and abortion referendums, said Farrell. He denied that NGOs had captured the process and said recruitment methods had greatly improved since an incident in 2018 when a recruiter was suspended for selecting people through personal contacts.

Irish assemblies had great potential but were too tightly controlled and on occasion tasked with inappropriate topics, said Farrell, who said Ireland should learn from other countries. “The reputation of Ireland as a trailblazer doesn’t apply any more.”

Jane Suiter, a DCU professor and founder member of We the Citizens, said assemblies remained valuable democratic instruments. “It’s a way to insert citizens’ voices into the process that otherwise would be completely dominated by business, unions, civil society groups.” A recent assembly on biodiversity was “amazing” and a future assembly could play a role in the potential unification of the republic with Northern Ireland, she said.