The glorious glowworm – the ‘love torch’ of the invertebrate world

The stars rise, the moon bends her arc,

Each glow-worm winks her spark,

Let us get home before the night grows dark

So wrote Christina Rossetti, one of many poets, artists and romantics to celebrate the most remarkable of beetles: the glowworm (Lampyris noctiluca).

It would be hard to find an invertebrate more indelibly illuminated in our culture than the glowworm. But now the nights have indeed grown dark because we have banished these glorious green bioluminescent beams from our lives, driven them out with dazzling artificial LED lights and the pervasive cult of tidiness in the countryside.

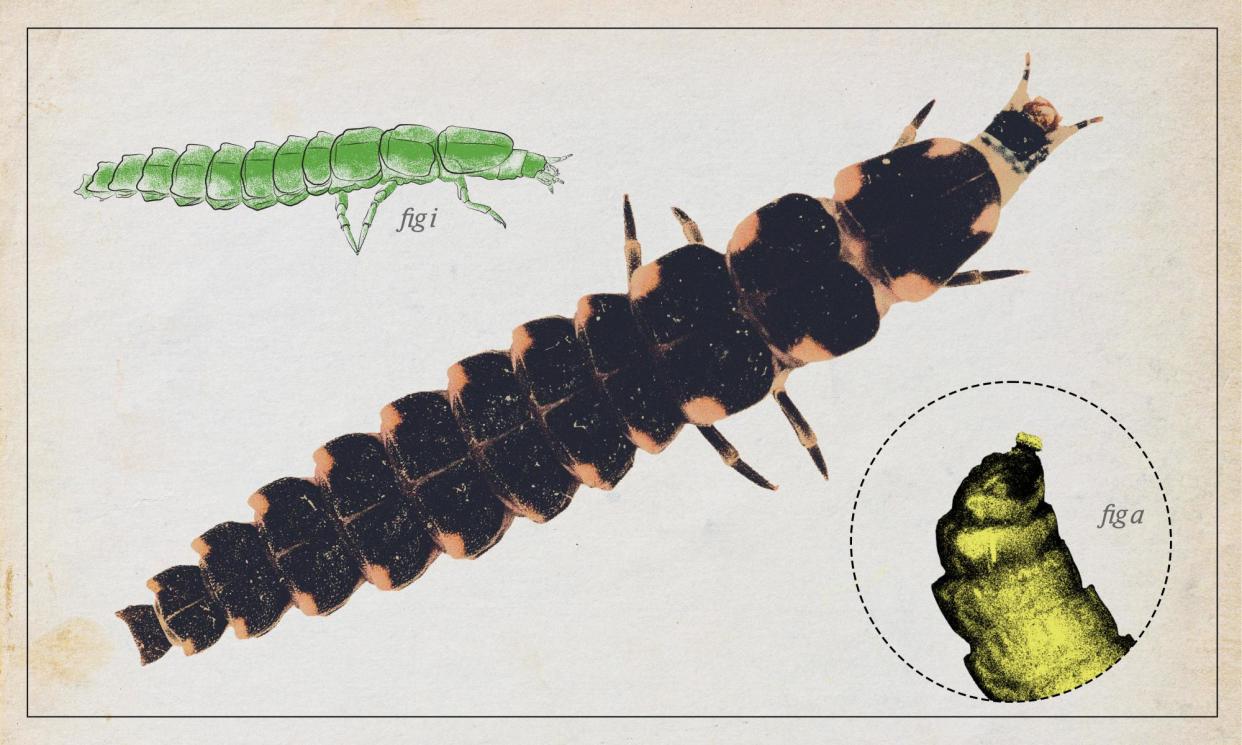

The lifestyle of these invertebrates is as striking as the beam emitted by the females to attract passing males. An egg laid in autumn becomes a 5mm larva with a voracious appetite for snails many times its size. The woodlouse-like larva lives for two summers, slowly growing to 20mm, jabbing its mandibles into its snail prey, delivering a neurotoxin that dissolves the still-living snail’s flesh.

After the larva pupates and emerges as an adult glowworm, it can no longer feed. The dull, glowless males, which look completely different from the females, develop wings and fly off in search of mates. The nocturnal, flightless females resemble larvae and appear clumsy and slow-moving with their six legs at the front of their body.

They have just two or three weeks to find a male, mate and lay eggs, and they meet this challenge by shining that brilliant light from the final sections of their abdomen. This greenish-yellow light is unusually cool but bright enough to help us see – soldiers in the trenches of the first world war used glowworms by which to read.

Beloved of Romantics such as Coleridge, for whom the glowworm’s beam was “a love torch”, there is something terribly poignant about the thought that this beetle’s silent signals go unseen in our illuminated world.

Glowworms still shine their lights on a warm June evening, most often on rough, calcium-rich chalk and limestone grasslands, in churchyards, railway embankments and even on the edge of London. But their populations have fallen rapidly in modern times along with most other common-and-garden insects. Use of pesticides, taking multiple cuts of meadows for silage rather than a single annual hay cut, tidying up gardens, global heating and droughts reducing snail populations – all have contributed to the loss of glowworms.

Several translocation schemes are under way to repopulate suitable habitat but the glowworm needs a boost. Light it up with your vote!