Who gets to ask the questions on Question Time?

Last Thursday, I appeared on BBC Question Time. On being told, when invited, that the venue would be the Bernie Grant Arts Centre in Tottenham, I had asked how the studio audience would be selected.

Bernie Grant was the local Labour council leader in 1985 when rioters in Broadwater Farm, Tottenham, murdered a policeman, Pc Keith Blakelock. He declared that “the youth think they gave the police a bloody good hiding”. The area retains its reputation for militancy. The balance of the studio audience is often a problem with Question Time. I suspected it would be particularly so in Tottenham.

The BBC reassured me: “There is an audience producer and 2 audience researchers whose role is to speak to and vet every member of the audience including in-depth social media checks to ensure that they are who they say they are and hold the views which they claim (which includes excluding extremist views). This … should mean the audience is more representative than your last appearance.”

Arriving, we were greeted by a small but noisy mob of pro-Gaza activists, who targeted a fellow-panellist, Wes Streeting. He and I arrived together, and security moved us fast to the door, but not before the apparent ringleader, a man with an enormously loud voice, yelled at Mr Streeting for supporting “genocide” and being a traitor to his gay sexuality (on the trans issue, I think). Mr Streeting remained calm and we passed inside. The beating of protesters’ drums outside continued through the evening.

The panel was as respectable as Mr Streeting – a Liberal Democrat MP, Munira Wilson, the policing minister, Chris Philp, and the amusing Lord Adebowale, chairman of the NHS Confederation. Fiona Bruce, 60 that day, presided pleasantly. There was no disorder.

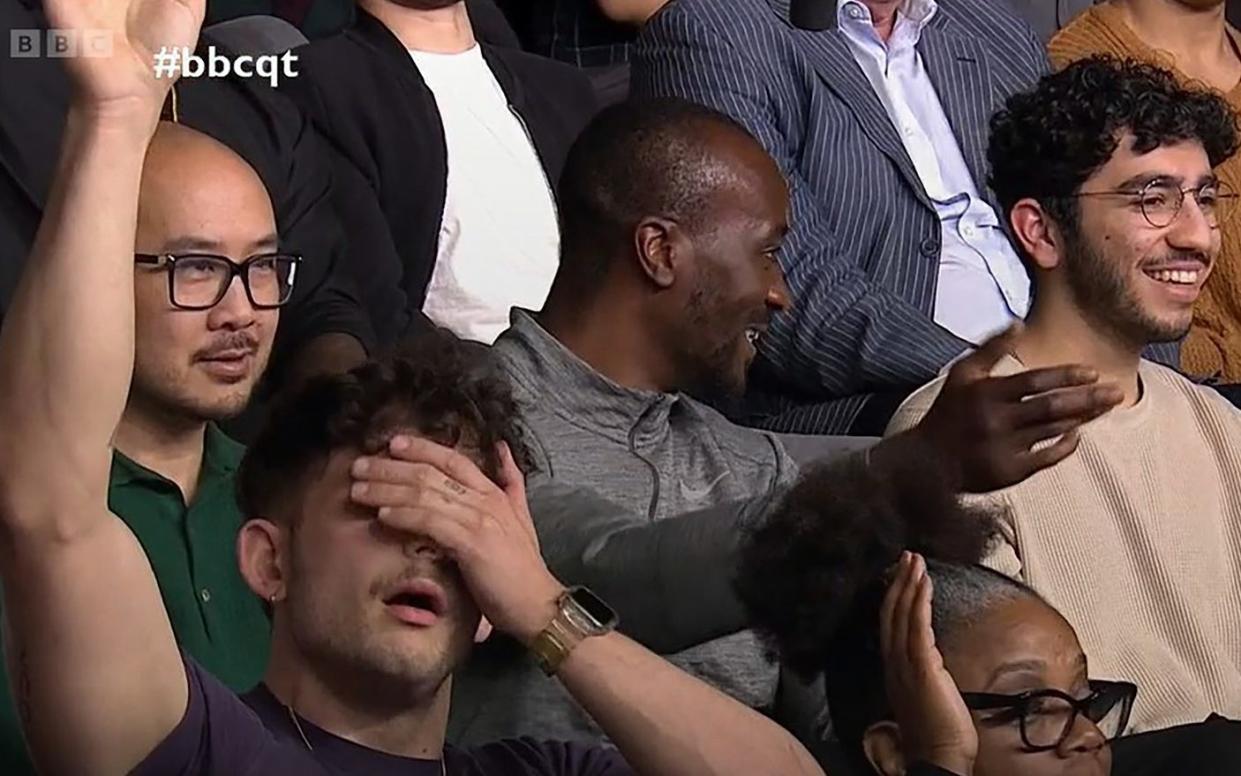

What there was, however, was the most unrepresentative audience unanimity. About 30 people, plus the three whose questions were called, must have spoken on air. Without, I think, a single exception, they all expressed Left-wing views.

For them, everything was the Government’s fault for not spending enough money. Rishi Sunak was a billionaire (he isn’t, actually) and so understands nothing. There should be no illegal immigration controls, let alone sending people to Rwanda. Everyone who wants a sick note should have one. The place was almost literally an echo chamber.

I was not personally ill-treated, but I did find it uphill work. The audience was so sure of its views that it was not interested in discussion. On rents, for example, I pointed out that if no-fault evictions are banned (the current crazy plan of Michael Gove), many landlords will leave the market, so rents will rise. This obvious truth seemed part-repulsive, part-incomprehensible to those present.

The main victim was not me, but the audience back home. Presumably they want a neutral atmosphere in which to hear a range of views. Most will be unpolitical and therefore uninterested in electioneering and slogans.

When I complained afterwards to the friendly staff, it was explained that the majority of those chosen had told the audience selectors they had voted Tory at the 2019 election. This prompts two questions. One is, “If they were a majority, why did you choose them? I thought you wanted party balance, not a one-party majority.” The other is, “Do you think they were telling the truth? If you cannot tell, don’t you need better methods of selection?”

Unfortunately, studio audiences today are the real-life equivalent of the Twittersphere – a space dominated by politicised people who want a fight. People of more small-c conservative views are usually shyer than the Left, certainly in the politically skewed BBC milieu. Which small-c conservative person would want to pipe up in a studio audience like last week’s? The problem reinforces itself.

This issue will become hotter in the coming general election debates as party supporters try to pack the audiences. If studio audiences are unrepresentative, how can the BBC perform its impartiality function? Should we opt for French-style election debates with no studio audience, or select to get a balance of views rather than nominal party allegiance?

It wasn’t like that in Sir Robin’s day

Before coming to Tottenham, I checked, and found that I first appeared on Question Time in 1987. I tried to compare then and now.

Then, there were only four panellists and far fewer audience interventions. Now there are five, and so much audience participation that the number of subjects covered falls (only three last week). The old show was pacier.

Forty years ago, panellists had dinner together beforehand, as still happens on Radio 4’s Any Questions? This made us feel friendly and relaxed. Now it is just a dreary snack, sometimes not even seated.

At that time, the presenter, Sir Robin Day, would sit with the guests at dinner and jolly us along. Now no one really acts as host or introduces panellists to one another. After the show, Robin Day would ring up or write to thank panellists. Today, nothing like that happens and you barely meet the chairman off air.

As the programme’s audiences have fallen, it has degenerated. Nowadays, the most important public figures do not want to take part.

One thing, however, has not changed in nearly 40 years – the fee. I think I got £150 then. I get £150 now, which works out, given the hours of preparation and travelling involved, at roughly the minimum wage. Not much for quite a bleak experience.