The furious bombardment that opened the US Civil War

There is much to be said for the brutality of a British general election, where a removals van turns up at No 10 within hours of a Prime Minister admitting defeat. In America, they manage these things differently, with a gap of two-and-a-half months between defeat and departure. Presidents become lame ducks; policies drift; decisive measures become harder to achieve.

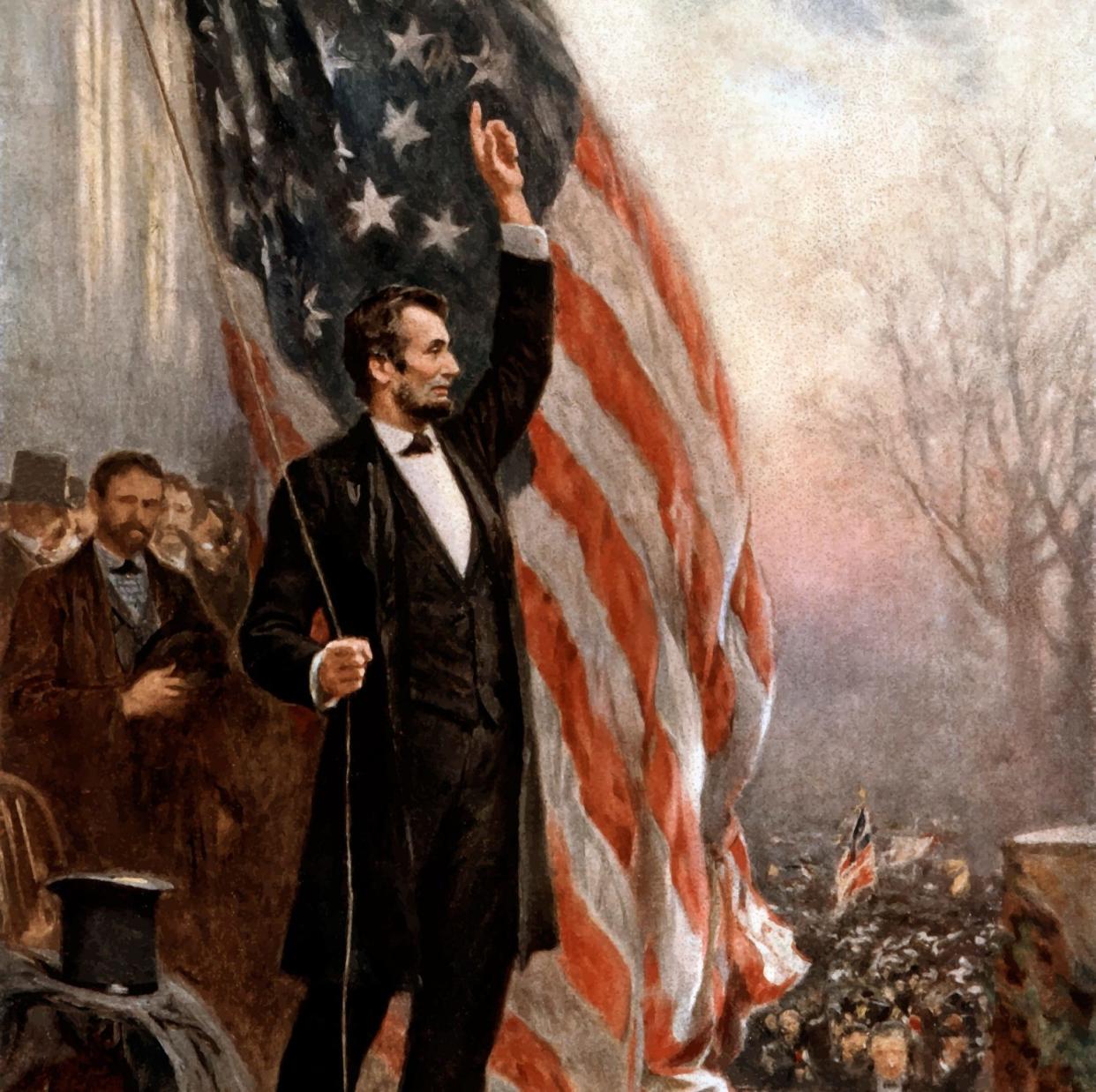

When Abraham Lincoln was elected president in November 1860, the gap was even longer, with his inauguration the following March. Never in American history had the need for clear and effective decision-making been so great; for the drift in policy in this case was a drift towards an appalling civil war in which more than 600,000 soldiers would die.

Erik Larson’s new book, The Demon of Unrest, is about that crucial period, plus the first five weeks of Lincoln’s presidency, after which a phoney war between North and South became a real one. So many volumes have been written about the origins of the American Civil War that one might heave a sigh at the thought of yet another, but Larson has found a genuinely original way of telling the story – and storytelling, on the basis of serious research, is what he does well.

Larson’s central focus is on Fort Sumter, an artillery fortress with brick walls five feet thick, on a tiny man-made island at the entrance to Charleston Harbour, the large bay outside the port-city of that name in South Carolina. The fort, still under construction at this time, belonged to the federal government; like several other nearby forts, it was manned by the US Army. When South Carolina declared its secession from the Union in December 1860, the forts’ commander realised that Sumter was the only one that could not be quickly overrun. In a masterly night-time operation, he shipped all his men there, and then politely declined a request from the governor of South Carolina that he surrender and leave.

The stand-off that followed transfixed the nation. The commander, Maj Robert Anderson, was lionised by many in the North, who thought the vacillating treatment of him by the government in Washington was shabby and demeaning. In the South he was portrayed as an aggressor; the most hot-headed secessionists actually longed for him to turn his guns on Charleston, as they wanted not just a war, but one clearly blameable on the North.

In fact, Anderson was himself a Southerner and a former slave-owner, whose personal sympathies were on that side. But, as a Southern gentleman, he had a code of honour; his oath of loyalty to his army and government took priority. So he did his duty with calm determination. When he defied the final ultimatum from South Carolina in mid-April 1861, and underwent two days of heavy bombardment – the first actual fighting in the Civil War – before agreeing to surrender his burnt-out fortress, he was praised for his conduct by friend and foe alike.

Around the suspense-laden story of Fort Sumter, Larson weaves a larger account of the political forces at work: the prosperous, proud, self-deluding slave-owners of South Carolina; the firebrand abolitionists in the North; and, caught between the two, the government in Washington, shifting this way and that as it tried to placate and pacify. James Buchanan, lame-duck president for most of this period, did not help the cause of the Union by declaring that while states had no right to secede, he would never use force against them if they did.

As for Abraham Lincoln: wrongly denounced by the South as an anti-slavery fanatic, this lawyer-turned-politician reluctantly accepted that Southern slavery was in accordance with the law, and just hoped that it would eventually fade away. But his legalism also told him that because Fort Sumter was a federal outpost, he had every right to reinforce it; his botched attempts to do so, in fact, may even have hastened the conflict.

Lincoln’s resolute constitutionalism was never in doubt – though the key arguments about states’ rights and secession are mostly skipped over here. But as Larson’s otherwise impressive account makes clear, in the first few weeks of his presidency he could be strangely irresolute in practical matters: another ditherer sliding down the slippery slope to war.

The Demon of Unrest is published by HarperCollins at £25. To order your copy for £19.99, call 0808 196 6794 or visit Telegraph Books