The day they set OJ Simpson free – and left America in turmoil

When the jury sent word they would deliver their verdict in the OJ Simpson double murder trial, the rest of America was caught by surprise, myself included. It had taken four hours to rule on nine months of evidence as to whether one of the country’s most famous black men had killed his former wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her young friend, Ronald Goldman.

It felt far too quick. The televised case in 1995 had been an astonishing spectacle, its twists and turns drawing vast numbers of viewers from the nation’s daytime soaps.

I had been covering the trial for the Observer, dropping in between other stories as the paper’s US correspondent. But I’d returned home to Washington DC, believing I had time before the result. And so, like President Bill Clinton and 100 million worldwide, I watched the verdict on television, a car waiting outside to take me to the airport. That journey across the US afterwards was through a cracked America. With the verdict minutes old, the white faces I saw in the streets were slack-jawed and silent. By the time I landed in Los Angeles, black people had filled the streets, celebrating. My car came to a shuddering halt as a man presented a placard to the windscreen: “The Juice Is Loose.”

I was heading for Brenda Moran’s house. She was juror number seven, 44 years old and a computer technician. I arrived to find a part of the circus that had so recently stood outside the Los Angeles criminal courts. Promises of all sorts were being made to the family for interviews. In the end, Moran gave a press conference on top of a parking garage, where she explained there had been no question as to Simpson’s innocence. “It didn’t take us nine more months to figure it out,” she said. “We’re not that ignorant.”

OJ Simpson – it’s short for Orenthal James – was arguably the best American football player of the 1970s. As a running back for the Buffalo Bills, a so-so team, his job was to carry the ball through opposition defence to “gain yards”, and he broke records doing so.

When that career ended, he turned to Hollywood, to advertising and parts in movies such as The Naked Gun series. He moved to Brentwood, buying a big property on North Rockingham Avenue (I know, I looked over the wall), and marrying Nicole Brown whom he met when she was 18 (he’d had to divorce his pregnant wife first). He then proceeded to beat and intimidate her.

Simpson had already begun to be considered something of a sell-out. His friends – and wife – were white. “He hated his own,” is how the US sports journalist Stephen A Smith put it. But that was about to change. He was about to become a golem to be carried against the institutional racism of the Los Angeles Police Department.

On Sunday 12 June 1994, Brown Simpson and Goldman were found stabbed outside her house. Her two children with Simpson were asleep upstairs.

As the focus turned on Simpson, he agreed to hand himself over to the LAPD. Instead, one of the oddest car chases imaginable began, broadcast live from helicopters, Simpson’s white SUV being trailed by police cars for 60 miles without ever breaking the speed limit. It sparked a national fascination that the writer Jeffrey Toobin, who covered the case day by day, said had everything: sex, violence, race and celebrity: “And the only eyewitness was a dog.”

Downtown Los Angeles lacks the soul of the city’s more famous neighbourhoods. It is echoing and municipal, and the criminal courts are no different. As the trial proper began in January 1995, a scaffold city grew up outside: Camp OJ, populated by technicians, reporters and anchors dressed fancy up top in suit jackets and ties, casual below in shorts.

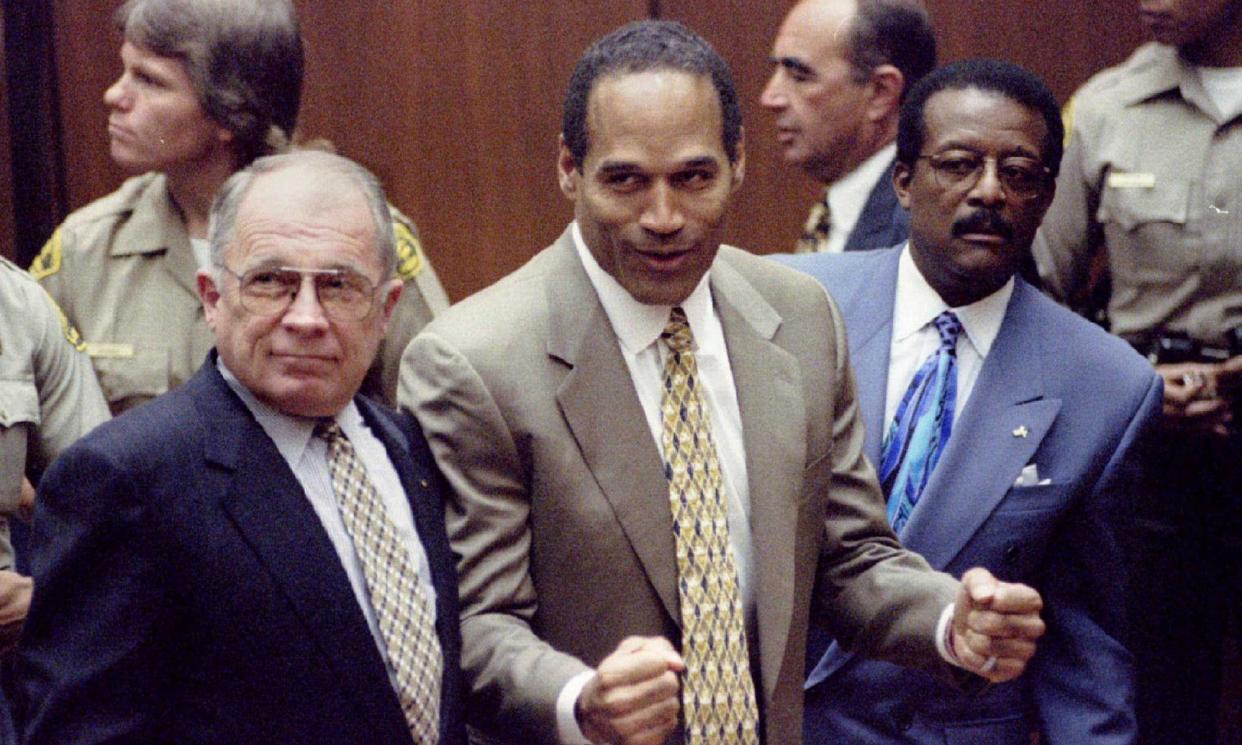

The courtroom itself was on the ninth floor, a secure space where the most contentious trials are held. We occasional visitors had to fight for our seats while paying homage to regulars such as David Margolick, who had also covered the Lorena Bobbitt “chopped penis” trial, and the celebrated investigative journalist and writer Dominick Dunne, who treated the show like Truman Capote might have. The true stars were the defence lawyers, among them Johnnie Cochran, F Lee Bailey and Alan Dershowitz. There was also Robert Kardashian, father of Kim. Simpson himself seemed a bit part. When, years later, the superb docudrama The People v OJ Simpson, was released starring John Travolta, Sarah Paulson and Cuba Gooding Jr, I was impressed at how trashy they made the whole thing look, but nothing could match the reality.

Much of this was down to the judge, Lance Ito, who let Court TV in and encouraged visiting celebrities. The courtroom’s tawny walls and judicial furniture were lit by an entire ceiling of light. The floor was always packed, and actors – say Richard Dreyfuss or James Woods – could be spotted working on their method. The hard currency was gossip. Did you hear about the evidence prosecutor Marcia Clark is choosing not to present? What’s your take on Simpson’s house guest, Kato (real name Brian) Kaelin, whose slacker surfer look seems more suited to Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure?

And yet, it turned out, Moran, juror number seven, was listening carefully. Twelve jurors and 12 alternates had been selected out of 304 possibles but attrition meant only four of the original 12 made it to the end. Ten of those were black. And given that the case was being heard downtown, rather than the fancier Santa Monica, most knew exactly how the LAPD conducted its investigations.

With no eyewitness, besides the dog, the prosecution presented DNA evidence that prosecutor Clark said ran in a “trail of blood from the crime scene through Simpson’s Ford Bronco to his bedroom at Rockingham.” The star piece was a bloody glove found in Simpson’s garden that matched another at the crime scene. Unfortunately, the police officer who found the glove encapsulated everything wrong with the LAPD. Mark Fuhrman seemed a character from central casting, right down to the evocative name (the defence would ultimately compare him to the Führer). Bailey asked if he had used any racist epithets in the past 10 years, to which he said no.

Bailey then produced swathes of evidence that proved him a liar, including a recording (he would later be convicted of perjury). A witnesses swore Fuhrman had a particular hatred of interracial marriages. This evidence landed hard in a city still scarred by riots following the police beating of Rodney King.

I didn’t have to walk far from the courthouse to find people – professional people – who told me that if the police wanted you, as a black person, they’d plant evidence. Even if the evidence did point to guilt, they’d still gild the lily, just to be sure. “And now they’re even doing it to OJ,” I was told.

Simpson’s acquittal didn’t bring him long-term relief. Soon a civil jury found against him and he was ordered to pay $33.5m to the victims’ families, which he had no hope of doing. In 2008, he was convicted of a bizarre robbery in Las Vegas involving memorabilia, and he spent nine years in jail. He collaborated on a book called If I did it.

Not many who followed the evidence believe he didn’t. Toobin, who may have written more than anyone else on the case, wrote the book that led to The People v OJ Simpson. In it, he wrote: “Simpson murdered his ex-wife and her friend.”

And yet, back in 1995, as I climbed to the top of the parking lot on that sunny Los Angeles afternoon to hear Moran talk about being sequestered as a jury member in the trial of the century, it did feel like justice had been done.

Not to Nicole Brown Simpson, Ron Goldman or their families. They received no justice. But the jurors had seen unsafe evidence presented, and had acquitted as was their duty under the standard of proof. Thanks to the LAPD, there was reasonable doubt. It felt like the whole rotten institution of policing in America stood convicted.

That’s what it felt like that day. Meanwhile, a few states to the east, a man called George Floyd was just about to celebrate his 22nd birthday.