As California posts America's best COVID numbers, Newsom's approval rises — and Caitlyn Jenner's recall hopes sink

Conservative critics of California Gov. Gavin Newsom seem to have made a serious miscalculation by seeking to recall and replace him this fall, new data suggests.

Three months ago, a plurality of registered California voters (48 percent) disapproved of the job the Democratic governor was doing, according to a poll conducted by the Institute of Governmental Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. Just 46 percent approved. The official recall campaign, which had launched a year earlier but only recently gained momentum, appeared to have a real (if still remote) chance of success.

But something else was happening three months ago as well: California was just coming off perhaps the scariest COVID-19 surge in America, averaging more than 500 deaths every day after enduring roughly 40,000 cases per day since Christmas.

Not anymore. Today, the Golden State has the lowest per capita rate of daily COVID-19 cases in the country — just 5 for every 100,000 residents, on average. More than half the population has received at least one vaccine dose. Bars and restaurants have welcomed customers back indoors. The vast majority of public school students have returned to classrooms. Few restrictions remain on businesses. And the entire state is set to fully reopen — and end its mask mandate — on June 15.

According to the latest Berkeley poll, Newsom’s numbers have recovered as a result, with a majority of Californians (52 percent) now saying they approve of his performance, versus just 43 percent who say they disapprove — a net shift of 11 percentage points. In contrast, then-Gov. Gray Davis’s approval rating fell into the 30s and then the 20s amid a prolonged electricity crisis before he was recalled and replaced by Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger in 2003.

And therein lies the problem.

Every California governor since Ronald Reagan in the 1960s has inspired quixotic recall petitions. Prior to February 2020, Newsom’s opponents introduced five recall petitions against him. None got off the ground. It was only when COVID started to spike over the holidays — and when Newsom seemed to be caught off guard — that the recallers were able to amass the 2 million signatures they needed to get on the ballot.

But recalling a governor because of the pandemic doesn’t make much sense politically, for the simple reason that in the time it takes to actually organize and hold an election, the pandemic is bound to look a lot different than it did before.

In Newsom’s case, it looks a lot better. And so do his chances of remaining in office (particularly in an overwhelmingly Democratic state like California when no other prominent Democrats are likely to appear on the recall ballot).

According to the latest Berkeley poll, the share of California voters who say Newsom has done a good or excellent job handling the pandemic is up 14 points since late January (to 45 percent), while the share who say he’s done a good or excellent job overseeing the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines is up 32 points (to 54 percent). Just 35 percent of California voters now rate Newsom’s pandemic leadership as poor or very poor — and, not coincidentally, just 36 percent of them say they support the recall effort.

To successfully recall a governor, more than 50 percent of voters have to vote to remove him on the first of two ballot measures.

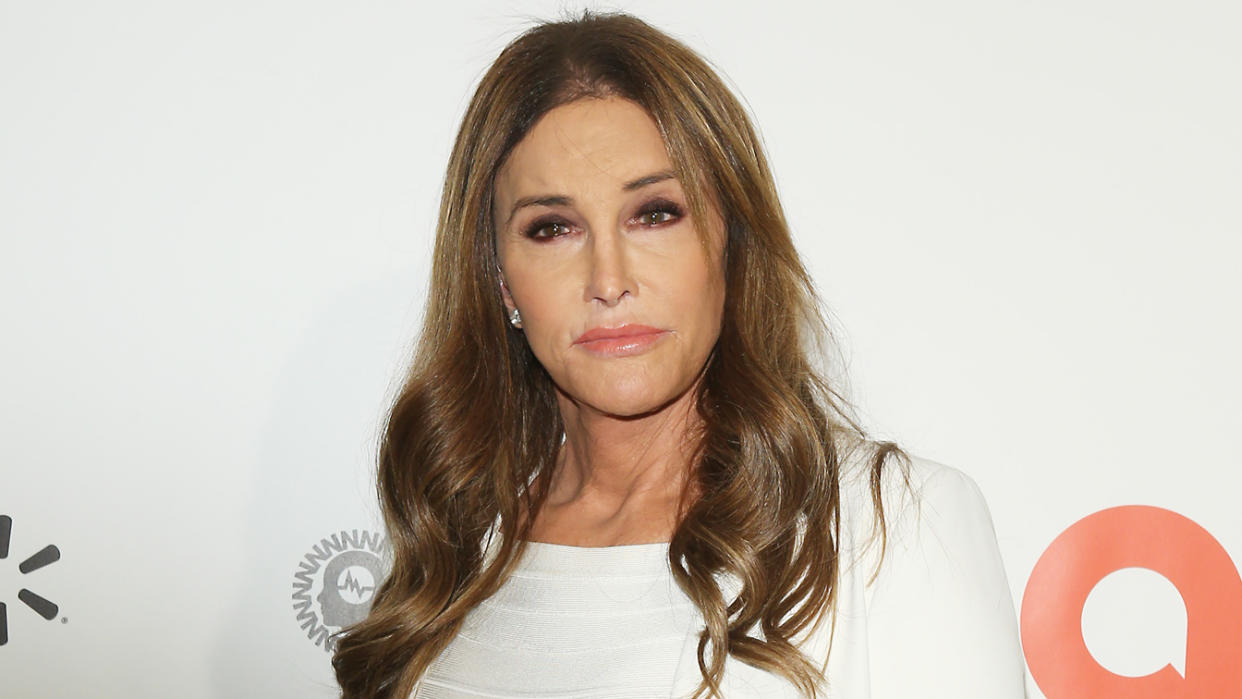

The second ballot measure, meanwhile, is about which challenger should replace the governor if the recall is successful — and Newsom’s opponents are faring even worse in that regard. For weeks, former Olympian and “Keeping Up With the Kardashians" star Caitlyn Jenner has hogged the media spotlight, but for all the wrong reasons: telling Fox News that a neighboring private plane owner at her airport hangar is abandoning California because he “can't take” seeing homeless people anymore, and claiming she didn’t vote in 2020 when records show she did.

The only one of Jenner’s GOP opponents to break through at all — businessman John Cox, who has already run five losing campaigns for office — managed to make news only because he brought a 1,000-pound Kodiak bear to his campaign appearances. The most theoretically formidable Republican candidate, former San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer, is barely registering at all.

According to the latest Berkeley poll, fewer than one-quarter of California voters are inclined to support Faulconer (22 percent) or Cox (22); near majorities (47 percent and 49 percent, respectively) already oppose them. And Jenner’s numbers are even worse. Just 6 percent of California voters favor her candidacy; more than three-quarters (76 percent) oppose it.

Throughout the pandemic, America’s governors have been judged for their response to a crisis that the Trump administration forced them to handle mostly on their own. These judgments have shifted over time.

In New York, Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo was initially hailed as a liberal hero for his frank, data-driven briefings, but the subsequent revelation that he dramatically and intentionally understated the pandemic’s toll on nursing home residents has damaged his reputation. In Florida, Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis’s push to downplay masks and fully reopen bars and restaurants looked foolish when case counts were high, then less foolish after warming weather and growing immunity helped the state avoid a fourth wave.

Newsom is no different; he rightly suffered last fall after making the deeply hypocritical decision to attend a lobbyist’s maskless birthday dinner at the French Laundry, a fancy Napa Valley restaurant, then suffered some more when the state’s winter surge collided with contradictory public opinion over restrictions and reopenings.

The only difference? Cuomo and DeSantis aren’t facing recall elections one year after the fact.

The truth is, a governor can control only so much about a virus that doesn’t respect state borders and spreads more because of how individuals choose to behave than anything else. Weather, demographics and emerging variants are also factors — none of which even the most powerful executive can change. Sure, a governor can help or hurt the situation by pulling various levers and sending various messages. When and what to reopen, and at what capacity? How to encourage (or, in some cases, discourage) masking? How to prioritize vaccine doses? And what about schools?

Now that the dust is starting to settle on the U.S. pandemic, it’s fair to ask how these governors performed. But it’s unlikely that the answers will decide their fate at the ballot box — or, with cases and deaths subsiding and immunity on the rise, drive a successful recall campaign.

Instead, California’s attention will likely revert to the problems that plagued it before the pandemic and will continue to plague it afterward: homelessness, housing, inequality and the high cost of living and doing business. Newsom is not invincible on these issues; the latest Berkeley poll, for instance, shows that 57 percent of California voters say the governor is doing a poor or very poor job on homelessness, while 53 percent give him poor or very poor job marks on housing costs.

This explains why Newsom said Tuesday that he was committing $12 billion toward the state's seemingly intractable homelessness problem — the largest amount of money spent at one time, he claimed, to get individuals and families off the streets. It also explains why he spent Monday touting the state’s surprise $76 billion surplus and pledging to send $600 stimulus checks to every Californian making less than $75,000 a year.

To actually recall the governor this fall, his challengers from the right will have to counter these proposals with ideas that sound more compelling to California’s largely liberal electorate than the ones Cox already peddled in 2018, the year he lost to Newsom with just 38 percent of the vote. The trajectory of the pandemic is no longer working against the governor; it’s working for him. Calling Newsom “the beauty” and mocking his French Laundry dinner probably isn’t going to cut it.

____

Read more from Yahoo News: