Bring back the pleasure of reading in classrooms

I read your editorial in delighted agreement with much of its argument (The Guardian view on English lessons: make classrooms more creative again, 2 May). My particular experience is working with the youngest children as they begin learning to read. Since 2021, schools in England have been required to follow the highly prescriptive systematic synthetic phonics (SSP) scheme. The “fully decodable” books approved for SSP schemes must focus on the spelling pattern to be learned, usually at the expense of a good story or any literary merit. Right from the start of school, enjoyment of books is being squeezed out.

However, your contention that the curriculum model of little blocks of tightly controlled content is “more suited to science and maths” must be challenged. My other role is as a maths tutor to teenagers. I find that they have been rushed to learn ever more complicated formulas and procedures without time to investigate ideas, to make links between topics or to develop thinking skills.

Mathematics is a deeply creative subject. Advances are made by finding new ways of thinking rather than by applying known formulae. Just as with English, the current fact-heavy GCSE and A-level maths curriculums squeeze out the joy of learning. A general curriculum review is needed. The soul has been knocked out of the English curriculum, but mathematics has been just as badly served.

Ruth Allen

Nottingham

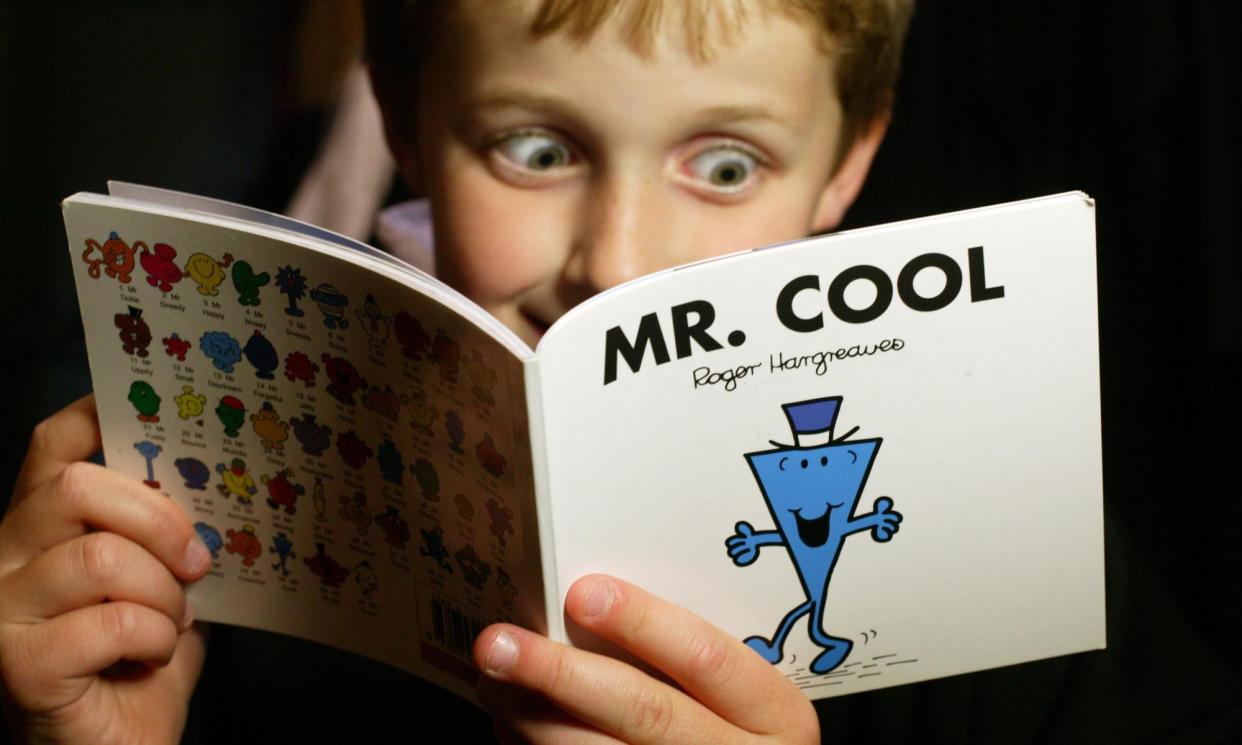

• It was so cheering to read your call for the pleasure of reading to be restored to the classroom. We all get the joy of sharing a picture book with young children, looking at the pictures, laughing together, perhaps enjoying the rhyme as we talk the words off the page. But for many children, that simple joy of reading gets lost when they learn to read.

They have to work hard to sound words out, and the story can become dull and restricted by what phonic sounds they are able to recognise. Language is stripped down to its component parts, reading becomes a chore, and parents and children get trapped in a reading battle.

Many schools are shifting the tide on this, and classrooms and corridors are beginning to buzz with reading-friendly spaces, brilliant books are positioned to tempt and children are encouraged to chat about their reading choices. But it’s an uphill battle. Let’s support schools, parents and carers to get children back to a place of sharing a book because they really want to. The benefits to all are clear.

Amy Lewis

Head of Coram Beanstalk

• I couldn’t agree more with your editorial. I have taught English at secondary level for almost 50 years. For the first 25 years or so, the text was king. We read, discussed, engaged, argued, talked about life, society, morality, emotion – literally everything writers write about. Then, gradually and insidiously, the assessment objectives and mark schemes usurped the text. Thinking and responding gave way to spotting. It became less important to discuss why Hamlet asks “To be or not to be?” and what that suggests about the human condition, and more important to identify the rhetorical device Shakespeare used.

Teachers became obliged to value what could be measured rather than continuing to teach what is valuable, and the subject became a shadow of its former self.

Mary Smith

Bearsted, Kent

• Do you have a photograph you’d like to share with Guardian readers? If so, please click here to upload it. A selection will be published in our Readers’ best photographs galleries and in the print edition on Saturdays.