Black mental health patients more likely to be injured at hands of police

The number of black inpatients injured while being restrained by police in mental health units has risen dramatically – at the same time as the number of non-black inpatients injured has fallen, according to analysis of government data by the Observer.

The Home Office’s police use of force statistics for 2022/23 show that police forces across England recorded 820 incidents of force used in mental health units against black inpatients, resulting in 36 injuries. This is up from the 770 use of force incidents and 27 injuries recorded in 2021/22.

Over the same time, use of force incidents against non-black inpatients decreased by 19% from 7,698 to 6,244, and resulting injuries fell from 559 to 406.

“These figures reveal that the shocking racial inequalities in our mental health services are only widening,” said Abena Oppong-Asare, the Labour MP for Erith and Thamesmead and shadow minister for women’s health and mental health.

This latest data covers the first full year since the main provisions of the Mental Health Units (Use of Force) Act came into use in 2018. The act, also known as “Seni’s law”, was introduced following the death of Olaseni Lewis, a 23-year old black man who died in Bethlem Royal Hospital in 2010, having been restrained by 11 police officers from the Met police.

These provisions require mental healthcare providers to develop and publish policies on the use of restraint, keep records of the use of force, and to train staff in de-escalation techniques to help reduce its occurrence.

Since August 2022, in the event that police are called to attend mental health units, they have been required to wear body cameras.

However, experts remain concerned that little has changed in practice.

“The family of Seni Lewis fought for this law, to ensure what happened to Seni never happened again,” said Lucy McKay, spokesperson for the charity Inquest.

“It is clear that the law and guidance has led to some important changes, but that has not been felt by black inpatients like Seni, for whom things appear to be getting worse.”

Ground restraint and limb and body restraint, two of the tactics used by police during the restraint of Lewis, rose by 9% and 20% respectively against black inpatients, while their use against non-black inpatients fell by 38% and 14%.

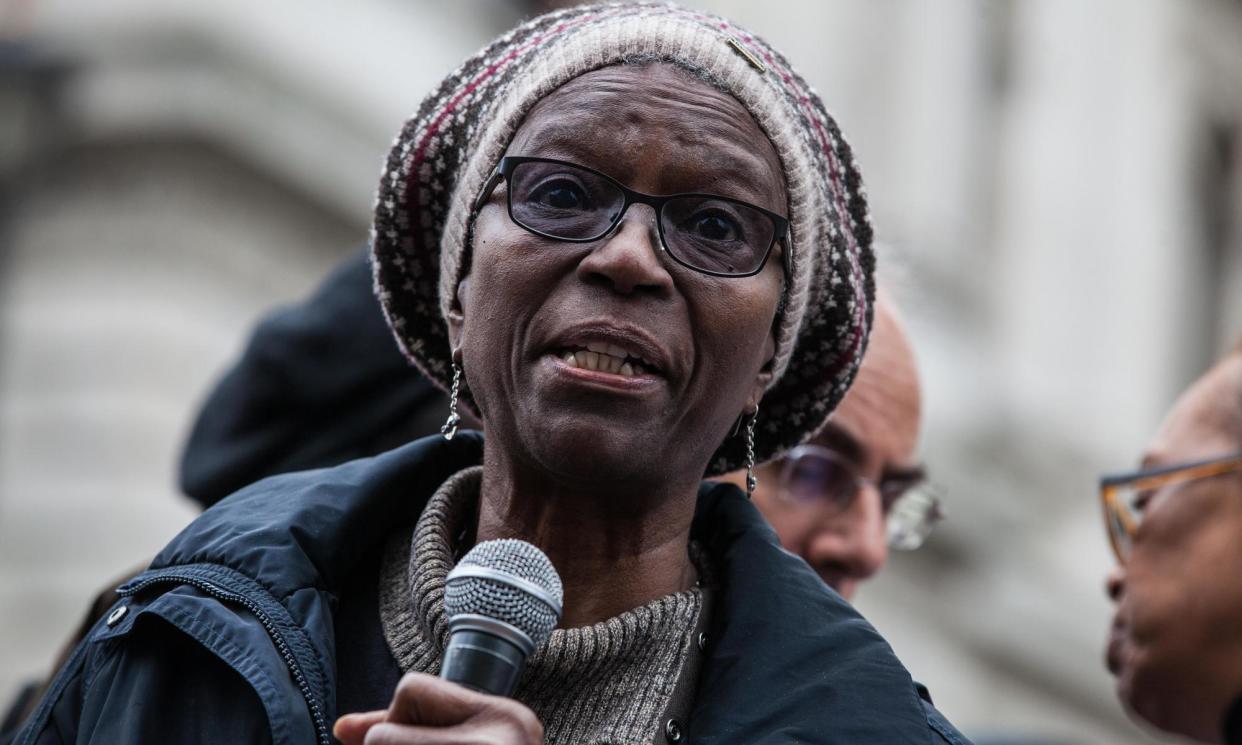

Aji Lewis, the mother of Seni Lewis and a campaigner on mental health, said: “Since my son died more than 13 years ago, we have fought to ensure he has a legacy. That legacy should be that what happened to Seni does not continue to happen.”

“The enactment of Seni’s law and the subsequent guidance was a positive step forward. Yet this data shows the change we need is not taking place. We must see urgent action to address continued racial disparities in restraint of patients, and to end the use of dangerous restraint of mental health patients.”

A Home Office spokesperson said: “Police officers must only use force where it is reasonable, necessary and proportionate to do so, in order to keep the public and themselves safe.

“Nobody should experience police use of force because of their ethnicity. We are making it easier for officers to use body-worn video and are providing local communities with more opportunities to scrutinise incidents of police use of force.”