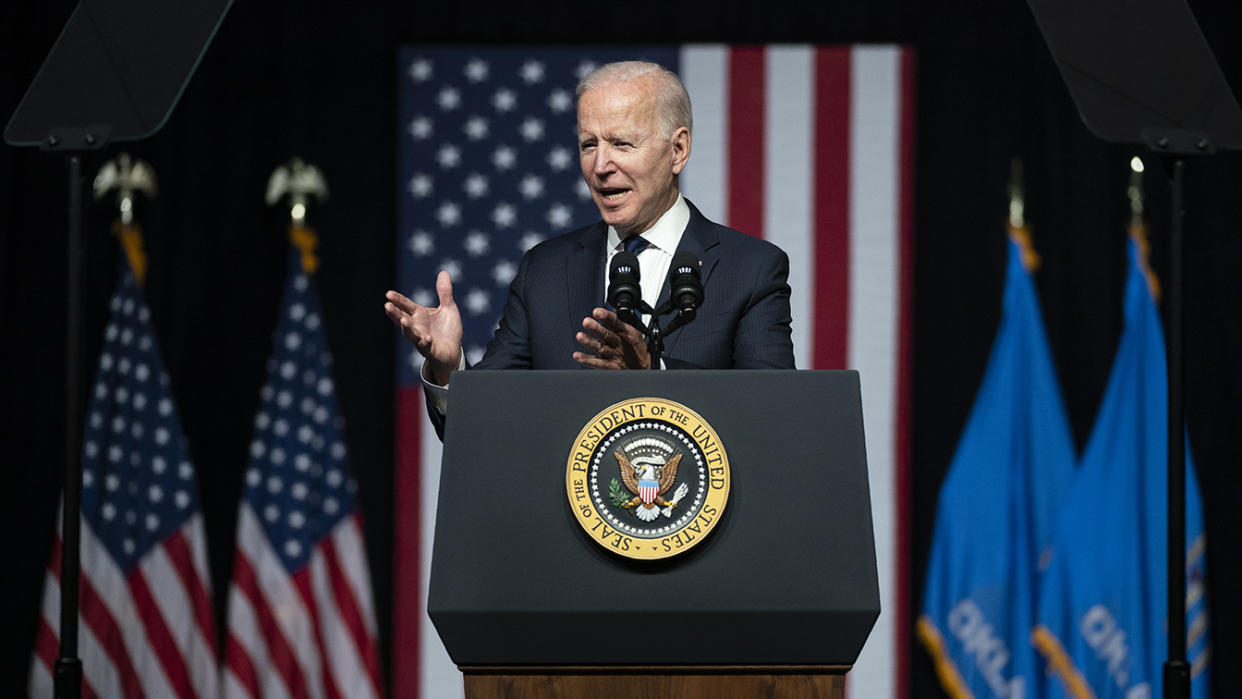

Can Biden close the racial wealth gap?

WASHINGTON — President Biden vowed on Tuesday to close the vast and persistent difference between the assets of Black and white Americans. That racial wealth gap stems from injustices going back to the era of slavery and is reflected today in factors like home valuation (much higher for whites) and access to credit (much harder for Black-owned businesses).

In all, the racial wealth gap was recently estimated by the Duke economist William Darity Jr. to stand at $11.2 trillion. Biden has offered nowhere near that amount, instead introducing a raft of proposed programs, such as $31 billion for small-business development and $10 billion for infrastructure upgrades in communities that had been neglected by Washington for generations.

Biden discussed the proposals in remarks after touring Greenwood, the Tulsa, Okla., neighborhood once known as Black Wall Street. The area was devastated a century ago by racist marauders who killed as many as 300 people. They also destroyed 1,256 buildings. The attack, and others like it around the nation, served to reinforce white supremacy in the wake of the Civil War and suppress the development of a Black middle class.

“It was a massacre,” Biden said as he toured the Greenwood Cultural Center on Tuesday afternoon. In subsequent remarks, the president quoted the Irish poet Seamus Heaney, telling his audience — which included three Tulsa Race Massacre survivors — that the nation may be in one of those rare moments when, as Heaney put it, “hope and history can rhyme.”

Great nations, Biden said, “come to term with their dark sides. And we are a great nation.” He said he had come to Tulsa to “fill the silence.”

Greenwood has only recently entered the national consciousness as a grotesque symbol of racial violence, as well as of racism’s lingering effects. The district never truly recovered from the massacre, and attempts at urban renewal — such as the construction of a freeway — only made things worse in Tulsa.

Biden now wants to reverse decades of what has come to be known as systemic racism. Although some of his proposals, like the infrastructure and business development funds, require the passage of his American Jobs Plan by a bitterly (and narrowly) divided Congress, others do not.

“We must find the courage to change the things we know we can change,” Biden said in Tulsa.

The president instructed the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development to focus on “countering housing practices with discriminatory effects.” Those practices have recently come under scrutiny, with historians uncovering the blatantly discriminatory practices of the Federal Housing Administration and other federal agencies that helped create the postwar white middle class while depriving Black Americans of the same upward mobility.

The result is that today, a house in a Black neighborhood is worth 23 percent less than a similar house in a similar neighborhood occupied by whites. That difference amounts to $48,000 per house, or $156 billion nationwide, according to a 2018 Brookings Institution analysis of Black asset ownership.

Ben Carson, who directed the federal housing department under President Donald Trump, dropped enforcement efforts when it came to housing discrimination.

The inability to buy a home has relegated many Black Americans to renting, preventing them from building equity that can be passed on to descendants. It can also leave them at the whim of landlords. Tulsa and many other cities have recently seen a wave of pandemic-related evictions, which have been especially devastating to people of color.

Biden also pledged that the federal government would devote $100 billion in contracts to minority-owned businesses. White-owned businesses have enjoyed a significant advantage in securing such contracts in the past.

The aspects of his wealth gap proposal that will need approval from Congress include $10 billion for “community-led civic infrastructure projects”; $15 billion for transportation upgrades; $5 billion for affordable housing, as well as, separately, a tax credit for developers of such housing; and $31 billion for small businesses.

The plan unveiled on Tuesday came just as Biden departed for Tulsa and was framed as a necessary step in a broader national recognition of racial iniquity. “The destruction wrought on the Greenwood neighborhood and its families was followed by laws and policies that made recovery nearly impossible,” said a White House press release announcing the wealth gap initiatives, noting that “the disinvestment in Black families in Tulsa and across the country throughout our history is still felt sharply today.”

During the presidential campaign, Biden drew criticism for waxing rhapsodic about the bygone days of congressional bipartisanship, when he, as a young senator, could work with unrepentant segregationists like James Eastland on certain issues.

As president, however, Biden has become a champion of racial justice, framing many of his proposals as a means to redress the depredations of the past. Aboard Air Force One on the way to Tulsa, principal deputy press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said the wealth gap proposals were part of what she described as Biden’s broader goal of “advancing equity and racial justice across the whole of federal government.”

Apart from the new wealth-gap measures, that has included loan forgiveness to Black farmers and grants for educators to teach about “the consequences of slavery, and the significant contributions of Black Americans to our society.”

Notably, student loan forgiveness was not among the plans proposed by the president on Tuesday, though some have argued that canceling student debt would help close the very racial wealth gap that Biden has now promised to address.

Neither was anything resembling outright reparations for the descendants of the enslaved. The call for racial reparations has grown louder in recent years, including for the descendants of Greenwood victims, having gained popular support via arguments by Ta-Nehisi Coates and other intellectuals.

The White House has said that Biden supports “studying” the issue of reparations but the president has never endorsed the issue outright.

Yet reparations are the preferred means of racial redress for some, including Darity, the Duke economist. He has endorsed cash payments, arguing that “incremental measures will not be sufficient to address the enormous racial wealth disparity.”

Biden’s proposed measures go well beyond those of previous administrations, but they are not enough for those who say that Biden cannot merely recognize the enormity of the problem without offering a solution commensurate with that problem’s size.

Writing in the Root, a news outlet devoted to Black affairs, the critic Michael Harriot — who tussled with then-South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg during the Democratic presidential primary in 2019 — offered that Biden’s proposals “won’t fix a single problem.”

____

Read more from Yahoo News: