Aphra Behn: the 17th-century spy at the heart of a sex scandal

One September morning in 1682, a bizarre advertisement appeared in the pages of the London Gazette. Readers learned of a missing person: a “young Lady of a Fair Complexion, fair Haired [and] full Breasted”.

This odd appeal was the opening shot in one of the most notorious sexual scandals of the age. Earlier that year, 18-year-old Lady Henrietta Berkeley had fled her parents’ house in Surrey wearing only “a striped petticoat”. She’d run away in pursuit of her sister’s husband, Lord Grey, who, it would transpire in a court-case, had seduced Henrietta when she was only 14. This revelation was far from the most shocking part of the affair. At one point, legal debate raged over Henrietta’s dirty underclothes, as the court tried to decide whether they could have belonged to a true “person of quality”. As if the adultery weren’t salacious enough, after being found guilty and while awaiting punishment, Lord Grey joined an armed rebellion against the Crown.

The Berkeley case, from today’s viewpoint, seems almost parodically 17th-century, a pastiche of the libidinous court of Charles II. But Henrietta is also, historian Lisa Hilton thinks, a useful foil for thinking about Aphra Behn, the 17th-century playwright normally remembered as being, in Virginia Woolf’s words, the first woman who proved she could “make her living by her wits”.

There’s a decent reason for writing about Behn and Berkeley together. In 1684, two years after the court case, the first volume of a three-part story appeared: Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister. Published anonymously, and based on both the scandalous affair and the insurrection that followed, it has for many years been attributed to Behn. And despite their differences – Behn, a prolific but penurious writer; Harriet, an aristocratic daughter – Hilton claims that the two women were both “extraordinary because of what they were not. They both refused to ‘know their place’.”

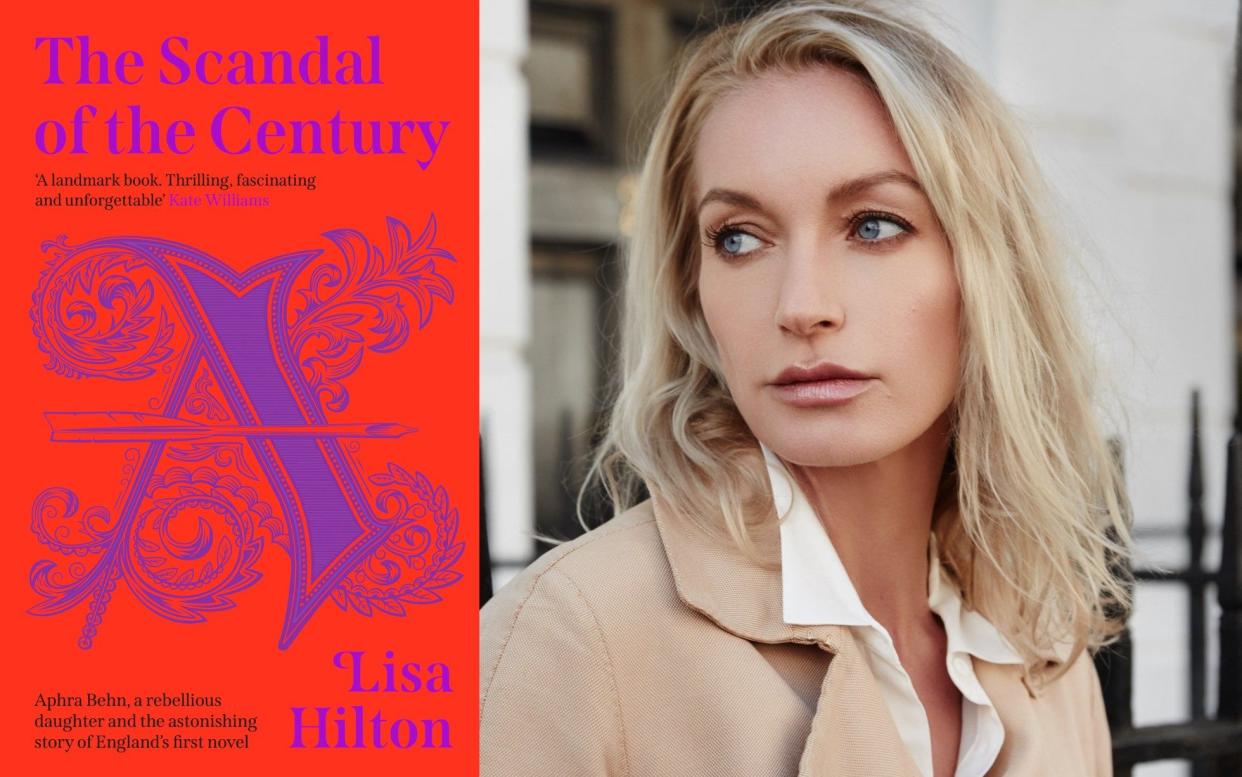

Yet The Scandal of the Century isn’t a joint biography. After her dirty laundry is aired in the introduction, Henrietta is cast aside until Hilton’s final chapters. Nor is this a traditional “comprehensive account” of a subject’s life. In Behn’s case, admittedly, such a book is hard to imagine: shockingly few facts are known about her, given her privileged spot in literary history. Janet Todd, her most thorough biographer to date, called her “not so much a woman to be unmasked as an unending combination of masks and intrigue”. Germaine Greer preferred to call her a “palimpsest”, a woman who “has scratched herself out”.

The facts that patient academics have “painstakingly teased” out about Behn’s life are as follows. She was probably born in 1640 to a barber in Kent, and likely travelled to Surinam – an English colony in South America – before she came back to Britain, and then worked as a spy in the Netherlands. She might have had a husband; she definitely worked as a scribe; and she eventually had her first play performed in 1670. She died in 1689, and is buried in Westminster Abbey. But these sentences hide a multitude of questions. Why is Behn all-but-invisible in parish records? What precipitated her Catholicism-infused work? How came she to be so well-educated?

After some discussion of how “relevant” Behn is today – which involves likening Restoration London to today’s young people, wearing “Gucci” shoes, “alert and on the make” – Hilton plunges into something bold. The Scandal of the Century throws out the Kent-barber theory of Behn’s birth, and replaces it with a more unexpected theory. Based on names dropped in Behn’s 1688 novel Oroonoko, and a putative mix-up between the village of Wye in Kent and the county of Kent in Maryland, Hilton argues that Behn could have been born in America, in a colony of Catholics. This “network of ghosts” is frail, but it could furnish some answers: it could explain Behn’s religion, her education, how she came to be a spy.

These details work towards constructing an alternative vision of Behn, woven from possibilities. And yet The Scandal of the Century still falls flat. Tied to Henrietta Berkeley’s case, the book remains more concerned with intrigue than historical specifics. Hilton includes few references, and sources are quoted without clear credit. Italicised notes appear every time the text comes up against something interestingly thorny. She dangles details in front of her readers, before whisking them away. More words are spent on the deficient feminism of the 17th-century court – Harriet “was not so much objectified as entirely reduced to an object” – than Behn’s trailblazing plays, in which Hilton seems uninterested. “It’s awkward,” she writes, to my astonishment, “that, frankly, 17th-century drama is a snore.”

Ultimately, the decision to yoke Behn to the woman at the centre of the Love-Letters makes for an uneven book, one that privileges sauciness over literary analysis, and undermines its own explorations of Behn’s life. It’s also on more shaky grounds than Hilton admits. In recent years, the attribution of the Love-Letters to Behn has come under severe scrutiny – something that Hilton doesn’t mention. With Behn, there’s always another mystery around the corner.

The Scandal of the Century is published by Michael Joseph at £22. To order your copy for £18.99, call 0808 196 6794 or visit Telegraph Books

Francesca Peacock is the author of Pure Wit: The Revolutionary Life of Margaret Cavendish