The pre-war prime minister who is to blame for Britain’s pothole crisis

The year is 1937 and the Vauxhall Ten has just rolled off production lines. The four-door saloon will revolutionise transport as one of the first affordable family cars. Britain’s roads, largely free from potholes, are as smooth as billiard tables.

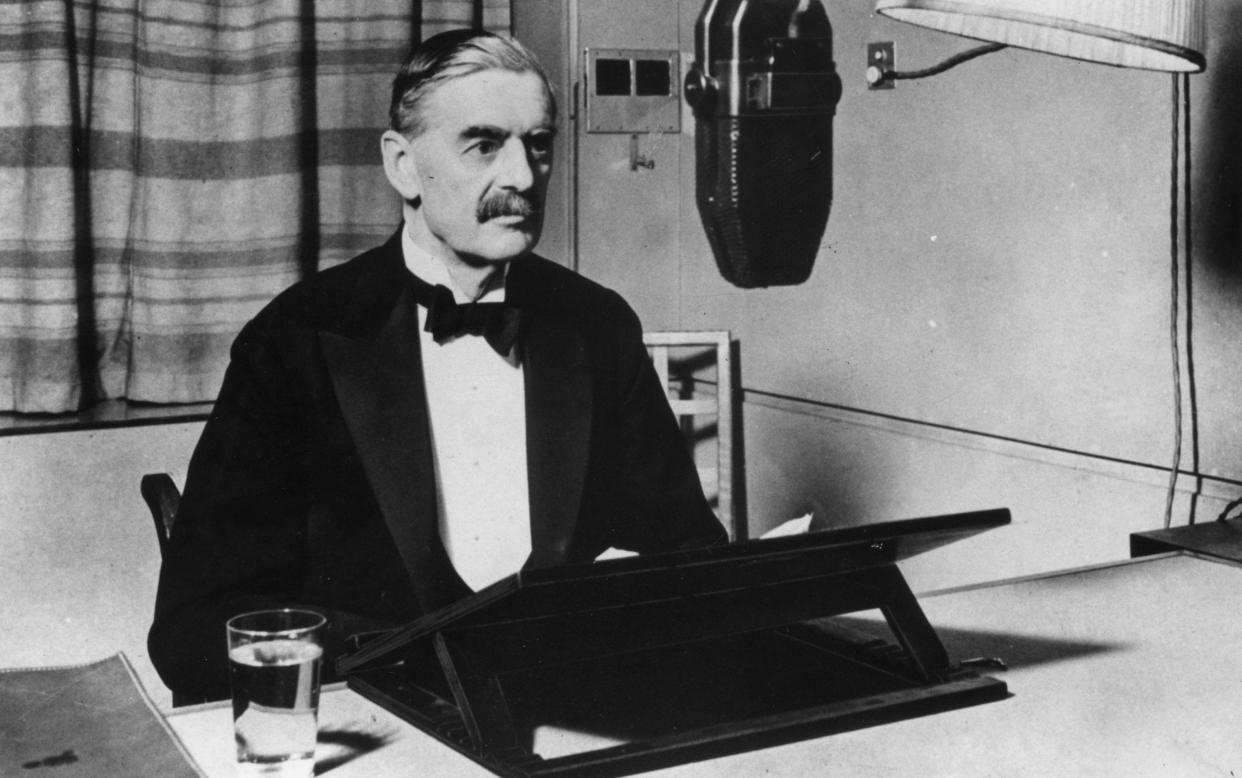

But a decision that year by Neville Chamberlain’s government to abolish a ring fence on vehicle excise duty (VED) that dedicated its revenues to road maintenance would preface decades of decay and underfunding.

Today there are said to be more potholes on British roads than craters on the surface of the Moon. Last year, drivers reported a record 1 million potholes across the country, according to comparison site Confused.com. The AA estimates the cost of fixing the damage can easily amount to £5,000.

While Neville Chamberlain is more often remembered for his failure to prevent the outbreak of the Second World War, his impact on British transport is far from insignificant. Since the former prime minister left Number 10, the money generated from car tax no longer goes solely towards road improvements.

Linking the proceeds of VED to a protected fund to rejuvenate our roads and highways has been suggested as one way to solve the UK’s pothole epidemic.

Edmund King, of the AA, believes VED should be used to create a national protected fund that can be used to pay for future road improvements. “You need all the money to be ring fenced so it is spent on maintenance,” he said.

“If you had a fund from VED that could only be spent on maintenance it would give you the long term funding and also allow you to invest more in the technology that is needed to repair the roads.”

It’s a widely held view across the motoring industry that taxes on drivers – which are set to become more profitable for the Treasury than those on smokers – should be used to improve and maintain the roads.

Hypothecated tax

VED was formerly hypothecated, meaning all the proceeds of a tax are spent on one particular purpose. The money now goes straight into general taxation instead, with the biggest expense being the NHS.

There are few governments in the Western world which still hypothecate their taxes. A common misconception is that the UK’s National Insurance tax is ring fenced to fund the NHS and social care, with shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves recently appearing to make this error in a post on X.

Martin Daunton, emeritus professor of Economic History at the University of Cambridge, said there are good reasons why the Government chooses to put all tax revenues in the same pot.

He said: “It goes back to Gladstone. One of the principles that he laid down, which the Treasury supported right through to today, was don’t hypothecate. Their view was if you hypothecate there would be more money coming in than you could possibly spend and then you would spend it in wasteful ways.

“There might be other ways of doing it and having a proper capital budget. Rather than having a concern over debt to GDP ratio, say we ought to have a budget sheet for the Government which is assets against liabilities just like a private company would.

“I don’t know if Rachel Reeves has gone down that road. That would be a better way of looking at it than hypothecation. Because of limited budgets of [local] authorities of all persuasion most of the money is going on social care so they can’t repair the roads.

“The potholes result from a lack of past maintenance repairing the roads. The issue is more to do with the problem of running down capital spending. It’s the same with your house, if you don’t paint your windows every five years they are going to rot and therefore you end up with more expenditure,” he added.

Britain’s roads are just 15 years away from failure

The bill for fixing the UK’s potholes is estimated to be in excess of £16bn, according to a study by the Asphalt Industry Alliance (AIA), the industry body for highway maintenance.

Just two years’ worth of VED revenues, currently forecast to net the Treasury £8.8bn between 2025 and 2026, would be more than enough to meet the cost. But the Government has continued to fund roads on an ad hoc basis.

Rishi Sunak recently used the surplus budget from the scrapped northern leg of HS2 to direct £8bn into repairs to be delivered over the next decade. The money was hailed as a “game changer” by the AIA in October.

Local authorities, which are responsible for maintaining almost all of the UK’s roads, receive lump sums year-to-year from the Government to invest in local highways. Councils have been accused of failing to spend the cash wisely and instead favouring quick fixes for potholes that do not stand the test of time.

Despite road repairs recently hitting an eight-year high, 17pc of roads were classed as poor in a survey last month by the Asphalt Industry Alliance (AIA). The same research warned that the majority of roads were just 15 years away from failure. Most sealed-surface asphalt roads must be completely rebuilt every 30 to 35 years.

Michael Enoch, professor of Transport Strategy at Loughborough University, said that dedicating tax to pay for road improvements was “retrograde”.

He said: “Potholes are the problem we have now but two years down the track we won’t have this problem and maybe want more spending on buses. I think dedicating taxes to pay for pothole improvements is retrograde, I don’t think it is the way forward.”

He added that implementing a national road pricing scheme for heavier bigger vehicles was one alternative.