The £635m tax scheme that went wrong

Hundreds of sports stars and celebrities will be receiving million-pound bills after the failure of a tax-avoidance scheme. Simon Wilson explains how it was supposed to work.

What has happened?

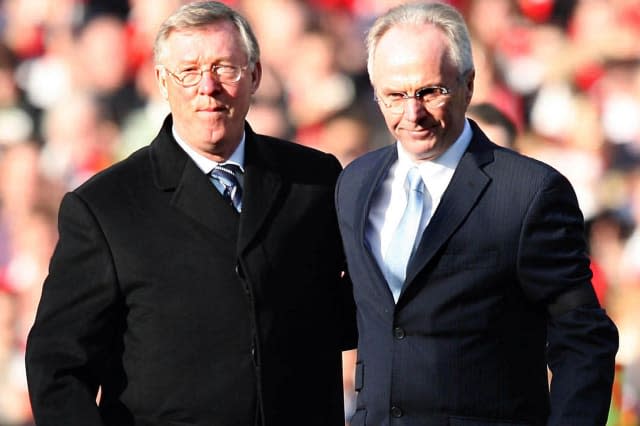

Hundreds of sports stars, celebrities and other wealthy individuals – reportedly including football managers Alex Ferguson and Sven-Goran Eriksson – are bracing themselves for "life-changing" tax bills running into the millions of pounds over a failed film industry tax-avoidance scheme, known as Eclipse 35.

It follows a four-year legal battle that ended in the spring, when the Supreme Court upheld the finding of a tax tribunal in 2012 (and of subsequent court hearings) that the Eclipse scheme was not a legitimate business that qualified for film industry tax relief, but merely a piece of financial engineering set up for the purpose of avoiding tax (£635m of it, estimates HM Revenue and Customs).

It is "highly likely" that 600 to 700 of the 780 people in the scheme would go bankrupt as a result of astronomical tax bills – many times greater than the original investment, Nick Wood, an adviser to hundreds of the investors in the scheme, told The Times last month.

How did the scheme work?

In essence, by claiming tax relief on a massive loan that was used to invest in film-distribution rights. The 780 members of Eclipse 35 put in a total of £50m in cash – in other words, a relatively modest average investment of about £64,000 – with Barclays then providing an additional £790m in loans.

Using this pot of £840m, the partnership bought worldwide distribution rights to two Disney films, Enchanted and Underdog, for £503m. It then immediately re-licensed those rights back to Disney for a total of £1,022m, spread over a 20-year period. That income would, over the same period, be used to repay the original loan.

How does all this save tax?

The idea was that, under the favourable tax rules available to investments in the film industry, the members of Eclipse 35 could then claim tax relief on the large interest payments they were making on the loan, totalling some £117m. In effect, the large loan created a "loss" for the partnership that could be offset (they hoped) against the investors' own tax liabilities.

Unfortunately (or fortunately, depending on your perspective), the taxman smelt a very large rat. HMRC argued that Eclipse 35 never carried on a trade – a pre-requisite for investors to qualify for tax relief – and that it had "merely organised a sophisticated financial model involving licensing and distribution rights".

Isn't this a legitimate business?

Eclipse 35 may have bought and licensed back film rights legitimately, but HMRC argued (and the courts have agreed) that the whole deal was structured with the overriding purpose of providing the members with debt interest payments on which they could then claim tax relief.

No doubt that verdict is pretty tough on some of the investors who relied on expert advice when making their investments (although less tough on the many tax accountants and other finance professionals who also invested and knew exactly what they were doing). However, what's especially harsh is that due to the scheme's structure, the tax liability they now have is far greater than the original investment.

How can that happen?

The tax liability is not just made up of repaying the "loss" that is no longer subject to tax relief. Unfortunately for the investors, they are also now liable for income tax on the income paid by the film production company to the partnership under the lease agreement. Of course, this "income" was used in practice to repay the loan part of the investment, and was never actually received as "income" by the investor.

But in the eyes of the law, and the taxman, it still counts as income – meaning these would-be tax-efficient investors could end up paying out around ten times the original investment in tax. Someone who put in £100,000, say, would need to find a million pounds in cash. Hence the potential bankruptcies among the scheme's investors, many of whom say they didn't understand the details and were never warned this might happen.

What are the lessons?

The Eclipse 35 ruling does not affect film tax relief (see below). Rather, it's a chilling warning for the various kinds of tax relief and deferral schemes that have sprung up over the past 20 years. Sometimes, these have crossed into outright criminality. Last year, for example, three former City traders were each jailed for 54 months for film-related tax fraud. (As they weren't actually "active members" of a film finance partnership, they didn't qualify for tax reliefs they had claimed).

But mostly, these schemes have not been illegal. The key question in the case of legal mass-marketed avoidance schemes is whether they will actually work. Here, increasingly, the key decision tends to come down to whether an actual trade been carried out. If not, then tax reliefs aimed at promoting investment do not apply, and investors may be in for a rude shock down the line.

Why do films get the star treatment?

Film production in the UK (and in lots of other countries) attracts generous tax breaks because the government sees the industry as a high-risk business, but one where favourable tax treatment that encourages investment can bring benefits to the wider economy. Under current UK rules, all films that are intended to be shown in the cinema (subject to various tests of "Britishness", which are not hard to pass) can claim tax relief at a rate of up to 25% of all money spent on producing the film.

This is subject to various conditions and in practice the relief usually works out at just under 20%, according to film producer Stephen Follows. The amount paid out under film tax relief between 2007 – when it was introduced in its current form – and March 2014 was £1.36bn, according to figures collated by Follows on his film data website. Similar tax breaks apply to some other creative industries, such as production of certain television programmes and video games.