The best way to profit from the Bank of England's bubble-blowing

Folks, I think the Bank of England may have just started another epidemic of asset-price inflation.

In the three months to July, it recorded an increase in the money supply that is unprecedented this century.

Yet instead of taking steps to slow things down, what has it done? Cut rates and begun another bout of quantitative easing.

You remember what happened after 2008. The question now is: where's all that money going to go this time?

Here comes another asset price bubble

Last week the Bank of England published its monthly report on the UK's money supply. In the three months to the end of July 2016 – so roughly a month and a half either side of the Brexit vote – it showed that the UK's broad money supply grew at 14.7%.

Very few, beyond economist Andrew Lilico, seem to have picked up on this number, but the implications are significant. Writing for Reaction Life, Lilico observes that before this, the strongest growth seen in this series since it began in 2009 was 8.7% – so we are ahead of that by a considerable margin. By six percentage points, to be precise – which, when you're talking money supply, is some number.

Lilico crunches some data back to 2002 and finds that this rate exceeds even the previous high of 12.8%, set in 2006 at the peak of the boom before the global financial crisis. We all know what happened next.

So what are the implications of this?

The meaning of the word "inflation" has been distorted. It has come to mean "higher prices", especially of everyday goods.

But used properly, in the original sense of the word, inflation means: "the blowing up of the supply of money and credit with the consequence of higher prices".

When the Bank of England – God bless it – measures inflation, all it does is track the prices of the various goods and services which make up the Consumer Prices Index (CPI). These include food and drink, clothing, furniture and household goods, transport and recreation costs and so on. From 1989 to now, CPI inflation has averaged about 2.8% a year.

But research by think tank Positive Money has shown that over the last ten years only about 10% of newly-created money has made its way into the kind of consumer items tracked by CPI. Instead, 37% has gone into financial markets, 40% into residential and commercial property, and 13% into real businesses that create jobs and boost economic growth.

So all the official measures do, effectively, is track the 10% of "inflation" that has gone into consumer goods. It's also worth noting that consumer goods face the deflationary pressures of improved productivity and competition and so on, which drive prices lower.

None of this should come as a huge surprise, and it probably doesn't. We all know that vast amounts of money have been created since the global financial crisis: whether via quantitative easing, low interest rates reducing the cost of existing debt (which otherwise might have been defaulted on) or the government issuing debt in the bond markets.

The financial markets have boomed – we've had record highs in the FTSE 100, record earnings for those who work in the financial sector, record property prices for the London houses in which they tend to live, record prices for the art which they buy – and so on.

In short, we have had rampant asset-price inflation. But, of course, the Bank doesn't measure that, not officially anyway.

It's been great if you operate in one of these sectors, but if you don't, you missed out.

So, given the direct link between money supply and asset-price inflation, and the wealth inequality this asset-price inflation has produced, you'd think that the Bank would want to do something about it when it saw this record 14.7% money supply growth to the end of July.

But instead of tightening things, Bank of England boss Mark Carney cut rates even further last month, and announced another round of quantitative easing.

Which sector will profit from the Bank of England's largesse?

I'm normally more of a technical guy than a fundamental one. I follow trends. But the asset-price inflation that the central bank reaction to the global financial crisis brought on is still all too clear in my mind.

Unless the Bank changes tack – which is unlikely – then it looks to me like we're about to see another bout of asset-price inflation somewhere.

The question is, where is all the money going to go this time? London property? Businesses? Fine art? The financial markets? Gold?

London property is a tough one. It is ridiculously expensive, certainly, but that doesn't mean prices can't go higher. For now, higher stamp duty costs are a deterrent and they've killed turnover. It's quite possible the new chancellor will lower these in his first Budget in November – there's no shortage of people lobbying him – but it's by no means a given.

And while the weak pound may make London look considerably cheaper to the overseas buyer, there is still this surfeit of new-build properties to get through. All in all, I'm not sure London property will see the gains it did after 2009.

Gold I already own, of course, and – at least measured in sterling – it might need to consolidate for a while.

So I suggest that a simple way for the ordinary investor to gain some exposure to all this might be to buy a bank. On a relative basis, it could even be argued that banks are cheap.

Anti-banking sentiment is not quite as vitriolic as it was, so they might not experience political attack in the way that they have in the recent past (and in the way that London property now is via stamp duty).

And as this money supply growth is, for now, specific to the UK, it makes sense to look at a UK-centric bank. I'm going to go with Lloyds (LSE: LLOY).

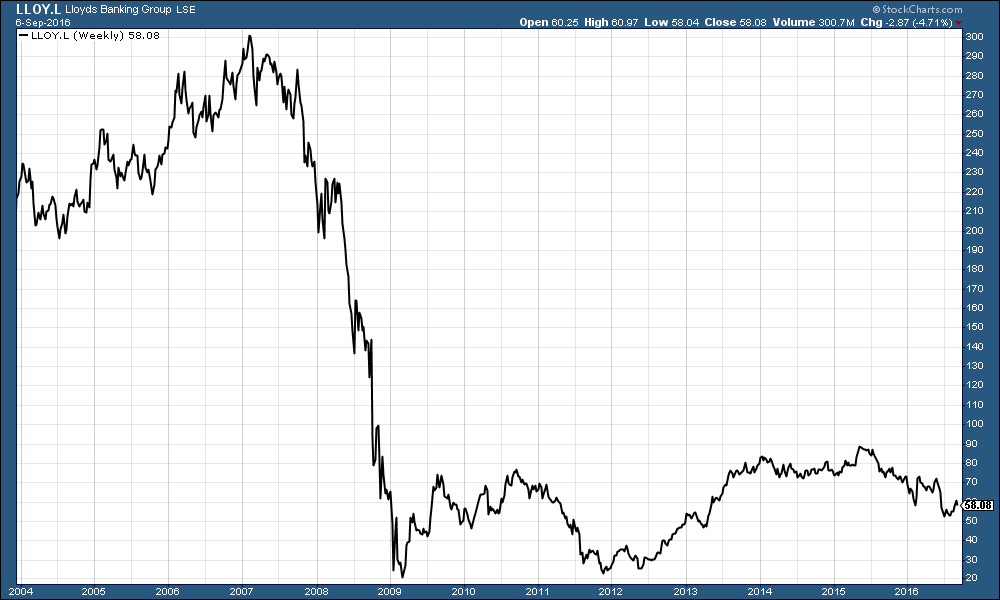

Below is a long-term chart for your reference.

It's in a bit of downtrend at the moment, but that seems to have reversed since the summer. Compared to its pre-2008 highs – you can see there's quite a lot of room up above.

The price/earnings ratio is 9.4 and a near-6% dividend is forecast for the next financial year, expected to be covered 1.9 times by profit. So there's value there.

And I know that my chum Charlie Morris over at the Fleet Street Letter has been writing a lot on the banks, so there must be something to it (if you want to know more on Charlie's views on the sector – and his favourite tips – then you should sign up for his newsletter here).

I can't believe arch gold bug, Dominic Frisby, is tipping a bank. That's the extent to which monetary policy is distorting behaviour. These really are strange times.