Brain implant aims to reverse Alzheimer's memory loss

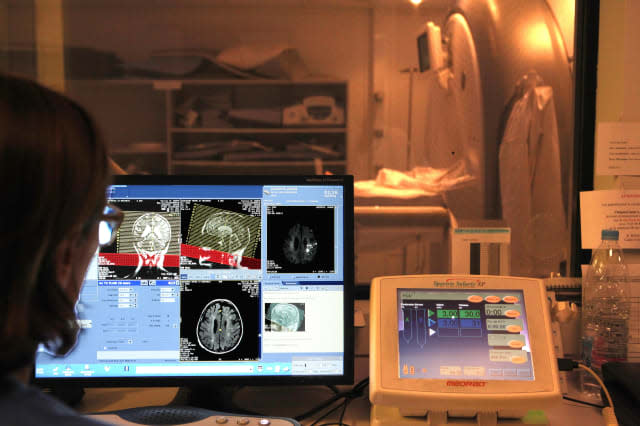

An electronic brain implant is being developed that has the potential to reverse memory loss.

The device is designed to replicate the function of the hippocampus, one of the first regions of the brain to be damaged by Alzheimer's disease.

Using a small array of electrodes, it effectively "translates" neural memory signals into a form suitable for long-term storage.

So far the implant has only been tested on animals.

An early study of nine patients who already had electrodes implanted in their brains to control epilepsy indicated the system was likely to work with 90% accuracy.

In the tests, scientists used computer software to record brain signals and mirror their translation in hippocampus.

"Being able to predict neural signals with the... model suggests that it can be used to design a device to support or replace the function of a damaged part of the brain," said Professor Robert Hampson, one of the scientists from Wake Forest Baptist University in the US.

Next, the team will attempt to send translated signals back into the brain of a patient with a damaged hippocampus to trigger the formation of long-term memory.

The research was presented at the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society in Milan, Italy.

Dr Clare Walton, research manager at Alzheimer's Society, said: "Although this sounds like the stuff of science fiction stories, the researchers are addressing a major problem for people with Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia - the ability to lay down new memories. The practical upshot of this is that people may have clear memories of events from their childhood but can't remember the details of what took place yesterday.

"The hippocampus is vital for remembering new events, people and places and it's one of the first parts of the brain to be damaged in Alzheimer's disease. In theory this device has the potential to help people to form new memories even when their hippocampus is damaged.

"A prosthetic memory device is a very exciting prospect, but it has taken decades of research to get this far and there are still many unknowns that need to be worked out by the scientists. It's encouraging to see these cutting edge technologies being applied to help people affected by memory loss, but this isn't something that people with dementia can expect to be readily available in the next decade."

The scientists explained that when the brain receives a sensory input, it creates a memory in the form of a complex electrical signal that travels through multiple regions of the hippocampus.

At each point, the memory is re-encoded until it ends up as a wholly different signal that is sent off for long-term storage.

Any damage that prevents this translation process means that a long-term memory cannot be formed. That is why someone with Alzheimer's disease can recall events from long ago - before the disease took hold - but have difficulty forming new long-term memories.